In every conflict over the living world, something is being protected, and most of the time, it is the wrong thing.

The world’s most destructive industries are fiercely protected by governments. The three sectors that appear to be most responsible for the collapse of ecosystems and erasure of wildlife are fossil fuels, fisheries and farming.

Last year, governments directly subsidized oil and gas production to the tune of US$64 billion, and spent a further US$531 billion on keeping fossil fuel prices low.

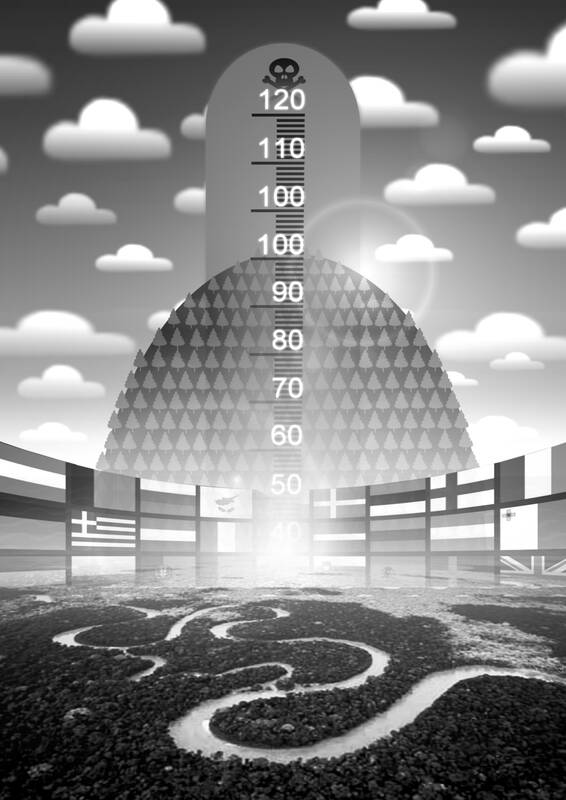

Illustration: Yusha

The latest figures for fisheries, from 2018, show that global subsidies for the sector amount to US$35 billion a year, more than 80 percent of which goes to large-scale industrial fishing.

Most are paid to “enhance capacity” — in other words to help the industry, as marine ecosystems collapse, catch more fish.

Every year, governments spend US$500 billion on farm subsidies, the great majority of which pay no regard to environmental protection. Even the payments that claim to do so often inflict more harm than good. For example, many of the EU’s pillar two “green” subsidies sustain livestock farming on land that would be better used for ecological restoration.

More than half the European farm budget is spent on propping up animal farming, which is arguably the world’s most ecologically destructive industry. Pasture-fed meat production destroys five times as much forest as palm oil does. It now threatens some of the richest habitats on Earth, among which are forests in Madagascar, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, Mexico, Australia and Myanmar.

Meat production could swallow 3 million square kilometers of the world’s most biodiverse places in 35 years. That is almost the size of India. In Australia, 94 percent of the deforestation in the catchment area of the Great Barrier Reef — a major cause of coral loss — is associated with beef production.

Yet most of these catastrophes are delivered with the help of public money. The more destructive the business, the more likely it is to enjoy political protection.

A study published this month said that chicken factories being built in Herefordshire and Shropshire, England, are likely to destroy far more jobs than they create, wrecking tourism through the river pollution, air pollution, smell and scenic blight they cause.

However, none of the planning applications for these factories has been obliged to provide an economic impact analysis.

Planning officers are highly dismissive of the hospitality industry, treating it as “non-serious and trivial,” the study said, adding that, by comparison, “attitudes to farming were very different; described as serious, ‘proper’ [male] work.”

The “tough,” “masculine” industries driving Earth systems toward collapse are pampered and protected by governments, while less destructive sectors must fend for themselves.

While there is no shortage of public money for the destruction of life on Earth, budgets for its protection always fall short.

US$536 billion a year is needed to protect the living world, the UN has said.

That far less than the amount being paid to destroy it — yet almost all this funding is missing. Some has been promised, scarcely any has materialized. So much for public money for public goods.

The political protection of destructive industries is woven into the fabric of politics, not least because of the pollution paradox: The more damaging the commercial enterprise, the more money it must spend on politics to ensure it is not regulated out of existence. As a result, politics comes to be dominated by the most damaging commercial enterprises.

Earth systems, by contrast, are treated as an afterthought, an ornament: nice to have, but dispensable when their protection conflicts with the necessity of extraction. In reality, the irreducible essential is a habitable planet.

In 2010, at a biodiversity summit in Nagoya, Japan, governments set themselves 20 goals, to be met by 2020. None were achieved. As they prepare for the biodiversity COP15 summit in Montreal, Canada, next week, governments are investing not in the defense of the living world, but in greenwash.

The headline objective is to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and oceans by 2030, but what governments mean by protection often bears little resemblance to what ecologists mean.

Take the UK, for example. On paper, it has one of the highest proportions of protected land in the rich world, at 28 percent. It could easily raise this proportion to 30 percent and claim to have fulfilled its obligations, but it is also one of the most nature-depleted countries on Earth.

How can this be? Because most of its “protected” areas are nothing of the kind.

One analysis said that only 5 percent of British land meets the international definition of a protected area.

Even these scraps are at risk, as scarcely anyone is left to enforce the law: The regulators have been stripped to the bone and beyond. At sea, most of the UK’s marine protected areas are nothing but lines on the map: trawlers still rip them apart.

All this is likely to become much worse. If the retained EU law bill goes ahead, the entire basis of legal protection in the UK could be torn down. Even by the standards of the British government, the mindless vandalism involved is gobsmacking.

To prove that Brexit means Brexit, 570 environmental laws must be deleted or replaced by the end of next year. There is to be no public consultation, no scope for presenting evidence and, in all likelihood, no opportunity for parliamentary debate.

It is logistically impossible to replace so much legislation in such a short period, so the most likely outcome is deletion. If so, it is game over for rivers, soil, air quality, groundwater, wildlife and habitats in the UK, and game on for cheats and con artists. The whole country would, in effect, become a free port.

Never underestimate the destructive instincts of the Conservative Party, prepared to ruin everything for the sake of an idea. Never underestimate its appetite for chaos and dysfunction.

The protected industries driving humanity toward destruction could take everything if they are not checked.

The world faces a brutal contest for control over land and sea: between those who seek to convert life support systems into profit, and those who seek to defend, restore and, where possible, return them to the indigenous people dispossessed by capitalism’s fire front.

These are never just technical or scientific issues. They cannot be resolved by management alone. They are deeply political.

The living world or the companies destroying it can be protected. Both cannot be done.

George Monbiot is a Guardian columnist.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s