The global obesity epidemic is getting worse, especially among children, with rates of obesity rising over the past decade and shifting to earlier ages. In the US, about 40 percent of today’s high-school students were overweight by the time they started high school. Globally, the incidence of obesity has tripled since the 1970s, with 1 billion people expected to be obese by 2030.

The consequences are grave, as obesity correlates closely with high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease and other serious health problems. Despite the magnitude of the problem, there is still no consensus on the cause, although scientists do recognize many contributing factors, including genetics, stress, viruses and changes in sleeping habits.

Of course, the popularity of heavily processed foods — high in sugar, salt and fat — has also played a role, especially in Western nations, where people on average consume more calories per day now than 50 years ago. Even so, recent reviews of the science conclude that much of the huge rise in obesity globally over the past four decades remains unexplained.

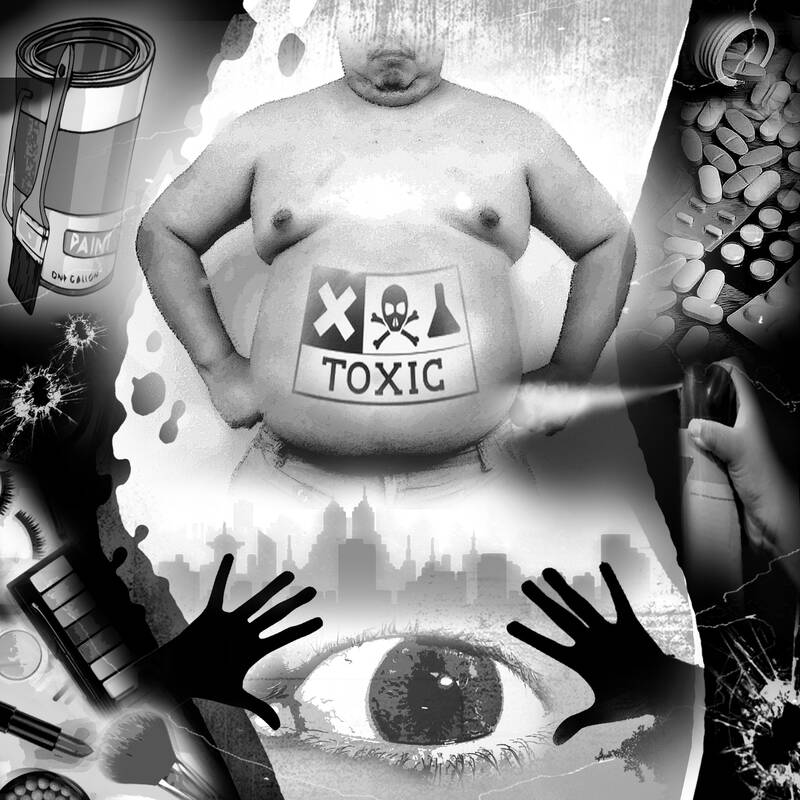

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

An emerging view among scientists is that one major overlooked component in obesity is almost certainly the environment — in particular, the pervasive presence of chemicals that, even at very low doses, disturb the normal functioning of human metabolism, upsetting the body’s ability to regulate its intake and expenditure of energy.

Some of these chemicals, known as “obesogens,” directly boost the production of specific cell types and fatty tissues associated with obesity. Unfortunately, these chemicals are used in many of the most basic products of modern life, including plastic packaging, clothes and furniture, as well as cosmetics, food additives, herbicides and pesticides.

Ten years ago, the idea of chemically induced obesity was something of a fringe hypothesis, but not anymore.

“Obesogens are certainly a contributing factor to the obesity epidemic,” Bruce Blumberg, an expert on obesity and endocrine-disrupting chemicals at the University of California, Irvine, told me by e-mail. “The difficulty is determining what fraction of obesity is related to chemical exposure.”

Importantly, recent research demonstrates that obesogens act to harm individuals in ways that traditional tests of chemical toxicity cannot detect. In particular, consequences of chemical exposure might not appear during the lifetime of an exposed organism, but can be passed down through so-called epigenetic mechanisms to offspring even several generations away.

A typical example is tributyltin (TBT), a chemical used in wood preservatives, among other things. In experiments exposing mice to low and supposedly safe levels of TBT, Blumberg and his colleagues found significantly increased fat accumulation in the next three generations.

TBT and other obesogens trigger such effects by interfering directly with the normal biochemistry of the endocrine system, which regulates the storage and use of energy, as well as human eating behavior. This biochemistry depends on a wide variety of hormones produced in organs such as the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas and liver, as well as chemicals in the brain capable of altering feelings of hunger. Experiments have shown that mice exposed to obesogenic chemicals before birth exhibit significantly altered appetites later in their lives, and a propensity to obesity.

OBESOGENS ABOUND

Nearly 1,000 obesogens with such effects have been identified in studies on animals or humans. They include bisphenol A, a chemical widely used in plastics, and phthalates, plasticizing agents used in paints, medicine and cosmetics. Others include parabens used as preservatives in food and paper products, and chemicals called organotins used as fungicides. Other obesogens include pesticides and herbicides, including glyphosate, which a recent study found to be present in the urine of most Americans.

A further clue that these chemicals might lie behind obesity is that the obesity crisis is also affecting cats, dogs and other animals living in proximity with people, studies have shown.

A significant rise in obesity incidence has even been noted in laboratory rodents and primates — animals raised under strictly controlled conditions of caloric intake and exercise.

Researchers believe that the only possible factors driving weight gain for these animals would be subtle chemical changes in the nature of the foods they eat, or in the materials used to build their pens.

So it is possible that humans have unwittingly saturated our living environment with chemicals affecting some of the most fundamental biochemical feedbacks controlling human growth and development. The obesity epidemic will likely persist, or grow worse, unless we can find ways to eliminate such chemicals from the environment, or at least identify the most problematic substances and greatly reduce human exposure to them.

At the very least, it will require a transformation in the way we test chemicals for their toxicity, especially the many compounds that are ubiquitous in our food, plastics, paints, cosmetics and other products.

Discoveries in epigenetics have deeply changed basic biological science and medicine over the past 15 years, but have not yet had much impact on prevailing practices for chemical safety testing. Scientists are pushing for changes, but it takes time.

Hopefully, appropriate test methods will be adopted within the next few years. If they are not, we might well struggle to make any appreciable dent in this pernicious epidemic.

Mark Buchanan is a physicist and science writer.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

After more than a year of review, the National Security Bureau on Monday said it has completed a sweeping declassification of political archives from the Martial Law period, transferring the full collection to the National Archives Administration under the National Development Council. The move marks another significant step in Taiwan’s long journey toward transitional justice. The newly opened files span the architecture of authoritarian control: internal security and loyalty investigations, intelligence and counterintelligence operations, exit and entry controls, overseas surveillance of Taiwan independence activists, and case materials related to sedition and rebellion charges. For academics of Taiwan’s White Terror era —

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

On Feb. 7, the New York Times ran a column by Nicholas Kristof (“What if the valedictorians were America’s cool kids?”) that blindly and lavishly praised education in Taiwan and in Asia more broadly. We are used to this kind of Orientalist admiration for what is, at the end of the day, paradoxically very Anglo-centered. They could have praised Europeans for valuing education, too, but one rarely sees an American praising Europe, right? It immediately made me think of something I have observed. If Taiwanese education looks so wonderful through the eyes of the archetypal expat, gazing from an ivory tower, how

China has apparently emerged as one of the clearest and most predictable beneficiaries of US President Donald Trump’s “America First” and “Make America Great Again” approach. Many countries are scrambling to defend their interests and reputation regarding an increasingly unpredictable and self-seeking US. There is a growing consensus among foreign policy pundits that the world has already entered the beginning of the end of Pax Americana, the US-led international order. Consequently, a number of countries are reversing their foreign policy preferences. The result has been an accelerating turn toward China as an alternative economic partner, with Beijing hosting Western leaders, albeit