At the conclusion of the UN climate summit in November, COP26 President Alok Sharma praised the “heroic efforts” of nations showing that they could rise above their differences and unite to tackle climate change, an outcome that “the world had come to doubt.”

It turns out that the world was right to be skeptical. Three months later, political intransigence, an energy crisis and economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic have cast doubt on the progress made in Glasgow, Scotland.

If last year was marked by optimism that the biggest polluters were finally willing to set ambitious net-zero targets, this year threatens to be the year of global backsliding.

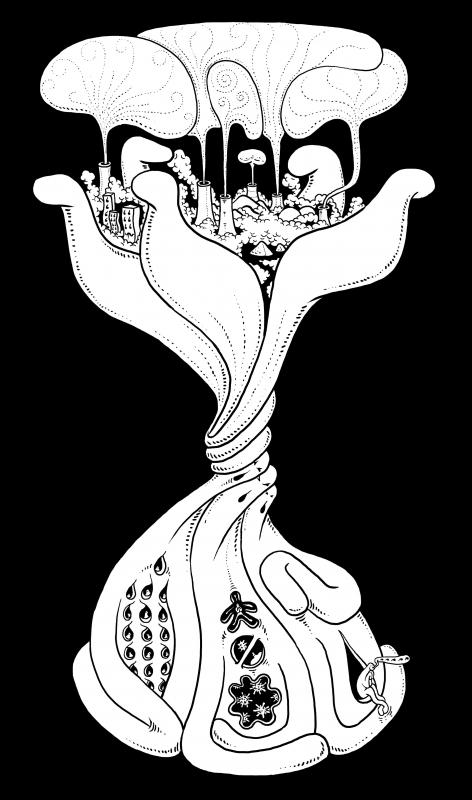

Illustration: Mountain People

From the US to China — in Europe, India and Japan — fossil fuels are staging a comeback, clean energy stocks are taking a hammering and the prospects for speeding the transition to renewable sources of power are looking grim. This is even as renewable energy costs have rapidly fallen, investment in clean technologies is soaring and voters across the world are demanding greater action.

“We’re going to have a multiyear stress test of political will to impose costly transition policies,” said Bob McNally, president of Washington-based consultant Rapidan Energy Group and a former White House official.

He accused governments of showing “Potemkin support” for the necessary policy steps, a sham display of action that is being exposed by the energy crisis.

Emissions rose last year, when they needed to decline if the world is to stay on track to hit climate goals. National interest was always going to run up against the kind of painful measures scientists agree are needed to meet the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C relative to pre-industrial levels, but even this early in the year, the headwinds to aggressive climate action are ferocious.

Oil is on a roll as the world economy picks up from its pandemic-induced swoon, nearing US$100 per barrel just two years after the price collapsed. That is swelling the coffers — and influence — of fossil-fuel giants such as Saudi Arabia and Russia, while reinvigorating an industry that had been shifting its focus to clean energies. Exxon Mobil Corp was just given a vote of confidence in the US shale industry with plans to boost output by 25 percent this year in the Permian Basin.

With natural gas prices hitting records, utilities have been turning to coal instead, despite it producing about twice the carbon, Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Kit Konolige said.

Even the UK host of COP26 risks regressing, with British Prime Minister Boris Johnson on the ropes and some members of his Conservative Party pushing back against his green agenda.

Little wonder that US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry has seemed increasingly glum, repeatedly warning that the world is falling behind.

“We’re in trouble,” Kerry told a US Chamber of Commerce event last month. “We’re not on a good track.”

For many, the highlight of COP26 was the surprise agreement by Kerry’s team and their Chinese counterparts to look beyond US-China rivalry and jointly raise climate efforts this decade.

That deal still stands, but the two nations have since backtracked in their respective actions.

The US last month was the world’s top liquefied natural gas exporter, taking the No. 1 spot from Qatar for a second consecutive month. Coal consumption has surged, while production last year climbed 8 percent, after years of declines.

Coal production is expected to edge upward through next year, the US Energy Information Administration has said.

In Washington, US President Joe Biden is struggling to get his signature Build Back Better bill and its core climate measures through the US Senate. An initial proposal, which would have devoted about US$555 billion to climate and clean energy, has collapsed amid objections from all of the Senate’s Republicans and a key Democrat, US Senator Joe Manchin of coal and gas-rich West Virginia.

Those climate provisions — including about US$355 billion in multiyear tax credits for hydrogen vehicles, electric vehicles and renewables — are essential if the US is to fulfill its commitment under the 2015 Paris Agreement to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 50 to 52 percent by 2030.

Without them, that pledge is in jeopardy, an analysis by the Rhodium Group found.

Rather than the leadership role that Biden has claimed, that makes the US look like a climate straggler.

Enacting the key provisions is needed to “empower us diplomatically,” Kerry said in an interview last month. “Credibility will be in a hard place if we don’t.”

Democrats in the US Congress are still hoping to revive the legislation, although there is little time with November’s midterm elections looming large.

Biden is also under pressure to confront rising inflation and especially gasoline prices, which could weigh on his chances of retaining control of Congress. He has responded by appealing to OPEC+ producers to boost output, asking domestic oil companies to drill more and rallying nations to join the US in a coordinated release of emergency crude stockpiles.

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is feeling similar pressure. Last month, in an effort to keep a lid on prices, his government announced subsidies for oil refiners worth about US$0.03 per liter of gasoline produced.

Amid reports that it might triple the subsidy rate, the Japanese government last week said that it was considering going further to mitigate the effects of rising oil prices.

All of this looks like a free pass to China, the world’s biggest emitter.

In several high-level meetings, Chinese officials have stressed energy security alongside efforts to reduce carbon emissions.

As the People’s Daily said in an opinion piece: “The rice bowl of energy must be held in one’s own hand.”

While top leaders have repeatedly stressed that China’s record-breaking build out of solar and wind power is part of a campaign to secure its energy future, the push has yet to tangibly shift the country’s energy mix. China’s share of coal and natural gas in power generation last year was as high as 71 percent, the same as 2020.

After an unprecedented power crunch that struck China in the second half of last year, Beijing was forced to raise coal output and imports to record levels.

At a group study session of the politburo last month, Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) said that supply-chain security should be guaranteed while curbing emissions, and that coal supplies should be ensured while oil and natural gas output need to “grow steadily.”

“Cutting emissions is not aimed at curbing productivity or at no emissions at all,” Xi said, adding that economic development and the green transition should be mutually reinforcing.

To illustrate Xi’s point, China last week offered its vast steel industry an additional five years to rein in its carbon emissions.

It is a sentiment shared elsewhere.

South African Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy Gwede Mantashe told the heads of mining companies on Feb. 1 that coal would still be used for decades and that rushing to end the country’s fossil-fuel dependency “will cost us dearly.”

India’s biggest coal miner, state-owned Coal India, is ramping up production as the country reduces its dependence on imports. It is exposing the carbon-dependent model of economic growth that the West used and that India is yet to walk away from, even after Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a net-zero target of 2070 in Glasgow.

India is the second-biggest coal user after China and a report by the International Energy Agency said that last year, coal accounted for 74 percent of power generation in India, followed by renewables at 20 percent.

However, ambitious plans to build out renewable capacity should shift that ratio. Billionaires Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani last year helped drive investment targeting alternative energy to a record US$10 billion, but that is dwarfed by Ambani’s new US$76 billion clean-energy plan.

“The world is entering a new energy era, which is going to be highly disruptive,” Ambani said last month as he unveiled his plans, which include achieving net-zero carbon emissions at his Reliance Industries — one of the world’s biggest oil refiners and plastics producers — by 2035.

The energy crunch has without a doubt cast a shadow on the EU’s debate about how to implement its Green Deal, an unprecedented economic overhaul to reach climate neutrality by 2050. Many governments are concerned that the spike in prices might undermine public support for the reforms.

The political atmosphere is not helped by the West’s standoff with Moscow over Ukraine, a situation that raises the threat of disruption to Russian gas supplies, stoking prices still further.

Higher fossil-fuel and emissions prices might improve the relative economics of renewables. EU leaders have in any case thrown their weight behind the Green Deal and with polls consistently showing climate to be among the biggest concerns for the bloc’s voters, the European Commission is doubling down.

Geopolitical tensions are compounding unusually high energy prices in the short term, European Commissioner for Energy Kadri Simson told reporters on Jan. 22.

“But we are also at a crucial point in our long-term effort to tackle the climate crisis and ensure a just clean energy transition,” she said. “The only lasting solution to our dependence on fossil fuels and, hence, volatile energy prices is to complete the green transition.”

Meanwhile, China last year added a record amount of solar power, and is likely to break that again this year, driven by a nationwide push for more rooftop installations and a mammoth build-out of renewables in the northern deserts.

In the US, private sector capital is racing ahead of the political will to enact meaningful climate policy. Globally, it totaled US$755 billion last year, BloombergNEF said.

The longer-term trend toward clean energy is undiminished. The current turbulence reinforces the fact that painful measures were always going to be required.

However, the cost of inaction is higher: Ten of last year’s worst climate disasters cost the global economy US$170 billion.

Even so, uncertainty is everywhere right now, said Christy Goldfuss, who was an official in former US president Barack Obama’s administration and is senior vice president of energy and environment policy at the Center for American Progress in Washington.

“It is accurate to look at this moment and be concerned about what progress looks like,” she said.

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

For Taiwan, the ongoing US and Israeli strikes on Iranian targets are a warning signal: When a major power stretches the boundaries of self-defense, smaller states feel the tremors first. Taiwan’s security rests on two pillars: US deterrence and the credibility of international law. The first deters coercion from China. The second legitimizes Taiwan’s place in the international community. One is material. The other is moral. Both are indispensable. Under the UN Charter, force is lawful only in response to an armed attack or with UN Security Council authorization. Even pre-emptive self-defense — long debated — requires a demonstrably imminent

Since being re-elected, US President Donald Trump has consistently taken concrete action to counter China and to safeguard the interests of the US and other democratic nations. The attacks on Iran, the earlier capture of deposed of Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro and efforts to remove Chinese influence from the Panama Canal all demonstrate that, as tensions with Beijing intensify, Washington has adopted a hardline stance aimed at weakening its power. Iran and Venezuela are important allies and major oil suppliers of China, and the US has effectively decapitated both. The US has continuously strengthened its military presence in the Philippines. Japanese Prime

After “Operation Absolute Resolve” to capture former Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro, the US joined Israel on Saturday last week in launching “Operation Epic Fury” to remove Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his theocratic regime leadership team. The two blitzes are widely believed to be a prelude to US President Donald Trump changing the geopolitical landscape in the Indo-Pacific region, targeting China’s rise. In the National Security Strategic report released in December last year, the Trump administration made it clear that the US would focus on “restoring American pre-eminence in the Western hemisphere,” and “competing with China economically and militarily