Days after flying into Glasgow to catch the opening of the COP26 climate summit, Santos CEO Kevin Gallagher headed over to Edinburgh to watch the Wallabies play Scotland from a corporate box.

The oil and gas company’s logo might have stood pride of place at the Australian pavilion at the summit, but it was the company’s sponsorship of the Wallabies that would prove a public relations coup.

The deal with Rugby Australia would see the team’s players display the Santos logo on the top-backs of their jerseys at every game.

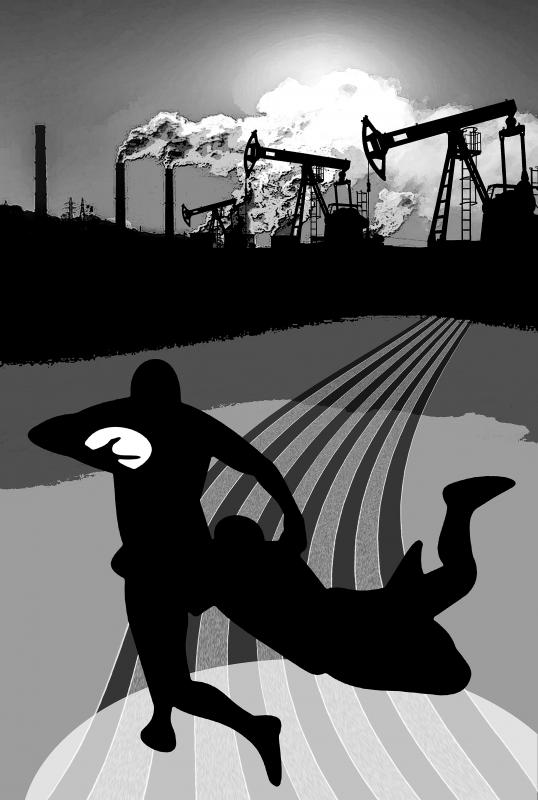

Illustration: Constance Chou

Former Wallabies captain David Pocock, a strong voice within sport calling for meaningful action on climate, said that “it’s hard to stomach.”

“I was always proud to represent my country. As a rugby player, that’s what you dream of. It’s been difficult to watch a partnership emerge with Santos,” Pocock said. “I really think fossil fuel sponsorship is the new cigarette sponsorship, where they are advertising a product that we now know is destroying our home planet and our futures.”

Oil and gas companies have spent billions to control the conversation on climate change and present themselves as “part of the solution.” The US$50 billion world of professional sport has proven to be catnip to an industry under pressure over its role in driving climate change.

Campaigns director for climate activist group 350 Australia, Kelly Albion, has been tracking fossil fuel companies as they negotiate sponsorship deals, advertising arrangements and official partnerships with arts organizations, community groups and sports clubs.

“There are some that are really hyper-local in places, while others are national,” Albion said. “It’s very opaque, so it’s hard to know how many of these are out there or what the relationship means.”

A count of these arrangements for which information is available reveals at least 12 fossil fuel companies, industry associations and energy retailers have 24 deals with sports clubs, stadiums or events at all levels.

As the list includes only those arrangements for which there is publicly available information, Albion said there might be others that are unknown.

SOCIAL APPROVAL

Among the most prolific is South Australian oil and gas company Santos, whose patronage extends to several sports organizations.

Even before it expanded its “long-term partnership” with Rugby Australia to include the Wallabies, Santos had sponsored the Wallaroos, Queensland Reds, New South Wales Waratahs, Western Force and the Australian Women’s Sevens.

Outside Rugby, Santos is the naming rights sponsor of the Tour Down Under, while it was announced in February that the company would sponsor this year’s Australian Open as “official gas partner” — although the company’s logo is not listed on Tennis Australia’s Web site.

The move was controversial as the 2014 Australian Open — where play was stopped and 1,000 spectators were treated for heat exhaustion when temperatures rose above 40°C — is considered an example of how climate change is detrimental to sport.

However, Santos’ sponsorship is not limited to the elite level. Earlier this year, the company sponsored the Festival of Rugby in Narrabri — headlined by rock band Thirsty Merc — where teams competed for US$25,000 in prize money, and the Aboriginal Power Cup, an Aussie rules football competition run in partnership with the Port Adelaide Football Club for Indigenous high school students in South Australia.

Santos is by no means the only fossil fuel company getting in on the action. Among the more high-profile examples are coal mining giant Adani’s sponsorship of the North Queensland Cowboys and the NSW Minerals Council’s partnership with the Newcastle Knights.

Meanwhile in Western Australia, gas giant Woodside Petroleum funds a learning-to-swim program with Surf Life Saving Western Australia, the “Woodside Nippers.”

A spokesperson for Surf Life did not answer questions about how much the relationship with Woodside was worth in dollar terms, but said it funded a range of beach-safety programs and “provides every child with a new uniform.”

“In 2019, the partnership extended to include the Nippers program in WA, helping us resource the program and our clubs, increasing opportunities to train children and their parents in beach and surf safety,” they said.

Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility director of climate and environment Dan Gocher said that the reluctance of clubs and companies to talk about the issue makes it difficult to assess the scale of the funding.

“The problem is you can never put a value on these relationships. You don’t know how much is at stake,” Gocher said.

Fossil fuel companies value these partnerships as a way to “buy social license.”

“In Australia, the way you wash your brand is through sport. Tobacco did it for a generation, through Formula One and AFL. Fossil fuel companies are essentially doing the same,” he said.

SPORT IS SPECIAL

At the height of its dominance, the tobacco industry turned the use of sport sponsorship influence into a fine art. In one case, a copy of speaking notes found in the archive of tobacco company RJ Reynolds reveals how by May 1980 it was sponsoring more than 2,400 sports events a year.

“That translates into 2,400 opportunities to put a politician in front of anywhere from 3,000 to 200,000 potential voters,” it reads. “An opportunity provided by Reynolds that’s too good to be true for the politician.”

The notes show the ambition of these relationships by crediting the company’s sponsorship of NASCAR racing for “killing tax increases in Florida and Alabama.”

Attempts to leverage the “soft power” of sport have not just been limited to tobacco companies.

Human rights organizations such as Amnesty International have repeatedly warned about how Saudi Arabia has bought up soccer clubs across the world as a way to water down criticism of human rights abuses.

Elsewhere, Russian state-owned oil giant Gazprom has spent billions sponsoring soccer clubs across Europe as it has expanded its gas infrastructure, even going so far as to sponsor the 2018 FIFA World Cup.

University of Melbourne marketing lecturer Robin Canniford said that sport in Australia is an obvious target for fossil fuel companies looking to protect their reputation as awareness of their role in the climate crisis grows.

“In Australia, sport is culture,” Canniford said. “Sport is special because of its emotional energy that you don’t get from many other areas of society anymore. Brands as symbols store, like a battery, emotional energy that sports fans love.”

Canniford said associating with sport in this way creates a “halo effect” for the company that allows it to “channel all that passion and energy” generated by sport.

LOOK TO THE FUTURE

While sport can be leveraged to further business interests, the UN attempted in 2018 to use sport to marshal support for meaningful action on climate change when it launched the Sports for Climate Action framework at COP24 in Katowice, Poland.

Although it has since attracted 273 signatories, only a handful of Australian sports institutions have signed on, including Tennis Australia and the Richmond Football Club. Both have yet to divest themselves of fossil fuel sponsorship, with United Petroleum still counted as a Richmond sponsor.

Former Socceroos captain Craig Foster said he welcomes Richmond’s work on climate change in other areas, but said “it has been very disappointing” to see the wider world of sport mute on the issue of climate change.

“Most of the advocacy is coming from athletes or former athletes in small groups, but the governing bodies that represent literally hundreds of millions of people, playing the most visible sports on the planet, have done next to nothing during the most important week when the planet is facing an existential crisis,” Foster said.

“I’ve said to these [sport] executives many times, get out of the past, get to the future,” he said. “Sports should recognize that dying industries such as fossil fuels do not represent the future of income.”

“Clean energy. Renewables. This is the new generation of sports sponsorships,” Foster said.

US President Donald Trump created some consternation in Taiwan last week when he told a news conference that a successful trade deal with China would help with “unification.” Although the People’s Republic of China has never ruled Taiwan, Trump’s language struck a raw nerve in Taiwan given his open siding with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression seeking to “reunify” Ukraine and Russia. On earlier occasions, Trump has criticized Taiwan for “stealing” the US’ chip industry and for relying too much on the US for defense, ominously presaging a weakening of US support for Taiwan. However, further examination of Trump’s remarks in

As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA) reach the point of confidence that they can start and win a war to destroy the democratic culture on Taiwan, any future decision to do so may likely be directly affected by the CCP’s ability to promote wars on the Korean Peninsula, in Europe, or, as most recently, on the Indian subcontinent. It stands to reason that the Trump Administration’s success early on May 10 to convince India and Pakistan to deescalate their four-day conventional military conflict, assessed to be close to a nuclear weapons exchange, also served to

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

China on May 23, 1951, imposed the so-called “17-Point Agreement” to formally annex Tibet. In March, China in its 18th White Paper misleadingly said it laid “firm foundations for the region’s human rights cause.” The agreement is invalid in international law, because it was signed under threat. Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, head of the Tibetan delegation sent to China for peace negotiations, was not authorized to sign the agreement on behalf of the Tibetan government and the delegation was made to sign it under duress. After seven decades, Tibet remains intact and there is global outpouring of sympathy for Tibetans. This realization