Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter, has committed to ending planet-warming emissions by 2060, but made clear that the new plan would not work if the country is stopped from continuing to pump millions of barrels per day for decades.

It is “an aim that enables us to say to the world: We are with you. We share the same concern. We want to evolve,” Saudi Arabian Minister of Energy Abdulaziz bin Salman said.

The country would take a “holistic and technological” approach in meeting the target, he added.

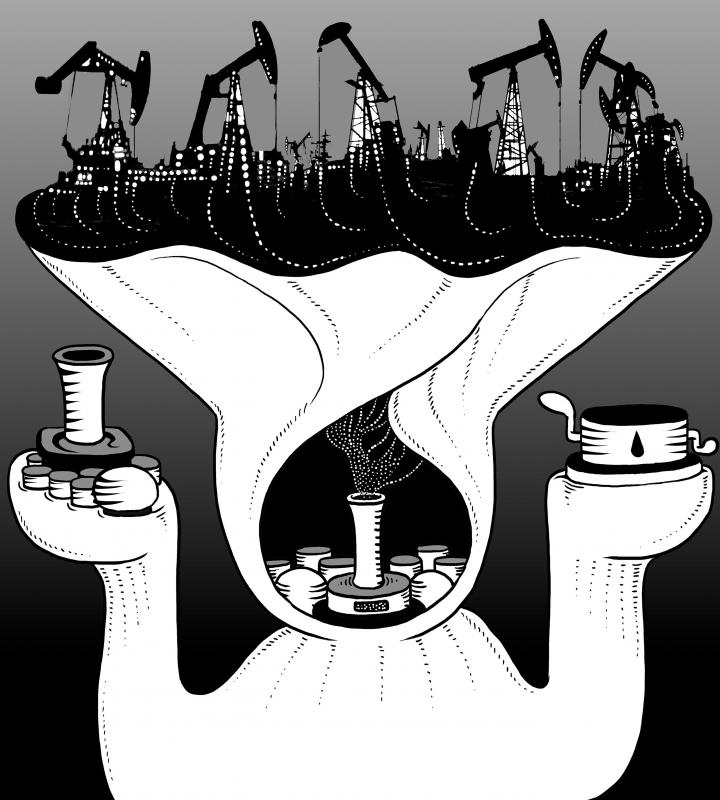

Illustration: Mountain People

The announcement might prove to be a boost for the COP26 climate summit that starts in Glasgow, Scotland, on Sunday, even as experts raise questions about the credibility of the goals set by the fossil-fuel giant.

The world “cannot operate without fossil fuels, without hydrocarbons, without renewables ... none of these things will be the savior,” bin Salman told the Saudi Green Initiative Forum. “It has to be a comprehensive solution.”

In global talks, such as G20 meetings or COP summits, Saudi Arabia often pushed for ensuring that fossil fuels have a longer-lasting role in the energy transition.

Only months ago, the energy minister told a private event that “every molecule of hydrocarbon will come out.”

The energy supply crisis the world is facing has given the country and its allies in OPEC more reasons to double down on the message, even though the reasons behind the shortages have less to do with green policies and more with a rapid rise in demand for energy after COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns.

“The world has sleepwalked into the supply crunch,” United Arab Emirates (UAE) Minister of State Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, who is chief executive officer at Abu Dhabi National Oil Co, told a panel discussion at the forum. “We cannot underestimate the importance of oil and gas in meeting global energy demands.”

While developing countries are seeking about US$100 billion annually to help finance the energy transition and build resilience against climate change, Saudi Arabia would not look to tap those sources.

“We are not seeking grants,” bin Salman said. “We are not seeking finance. We are not seeking any monetary support.”

Saudi Arabia, which relies on fossil fuel exports for the majority of its GDP, has struggled to diversify its economy.

The country’s cash cow, state-owned oil giant Saudi Arabian Oil Co, also set a goal to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, but only for emissions from its own operations.

More than 80 percent of the company’s total emissions come from customers burning its fossil fuels, which are not covered by the pledge.

Without continuing to export oil, the energy minister said that the country might not have the ability to reach those goals.

The nation has the highest per-capita emissions among G20 countries.

No country has a detailed plan for reaching net-zero emissions apart from the UK, which released a strategy document earlier this month.

The general contours involve increasing the share of renewables in the electricity sector, converting as much of the transportation sector to run on battery-powered vehicles as possible and then focusing on technology development for harder-to-abate sectors like industry and agriculture.

So what is Saudi Arabia’s plan for cutting emissions?

“We believe that carbon capture, utilization and storage, direct air capture, hydrogen, and low-carbon fuels are the things that will develop the necessary ingredients,” the energy minister said, adding that it would require “international cooperation in research, developing technologies and, most importantly, deploying these technologies.”

Saudi Arabia has also announced that it would join 35 other countries, led by the US and the EU, to cut methane emissions by 30 percent by 2030, relative to last year’s levels.

Scientists say that cutting leaks of the super-warming greenhouse gas is one of the quickest ways to slow down climate change.

Even though scientists have been warning about climate change for more than 30 years, it is only in the past few years that countries have come out and set net-zero emissions goals that are crucial if global temperatures are to be stabilized.

Green technologies would play an essential role in helping the world meet climate targets, but scientists agree that those objectives would not be within reach without reducing fossil-fuel extraction and use.

“Why 2060? Because most of these technologies may not mature before 2040,” bin Salman said.

The target year of 2060 matches the ambitions set by Russia and China, but it lags those set by other large economies like the US, the UK and the EU.

Even among petrostates, the UAE earlier this month set a net-zero goal for 2050.

“It’s an aspirational goal,” said Karen Young, a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute. “In some ways, it’s more of a branding exercise than an actual long-term policy commitment.”

Bin Salman reiterated a goal that the kingdom plans to increase the share of renewables to 50 percent of its energy mix, with natural gas covering the other half, by 2030.

That would require a huge change in less than nine years for a country where solar power barely registers today.

The country committed to investing 700 billion riyals (US$187 billion) in the green economy, without specifying the period over which that money would be spent.

“This will change the balance of COP,” said Marco Alvera, chief executive officer of gas logistics company Snam. “The private sector is very excited by all that’s happening in the Middle East and in the kingdom.”

The COP26 summit has been labeled a “make or break” moment for the planet.

UN officials welcomed Saudi Arabia’s announcement, saying that it would help the testy negotiations set to happen over the next few weeks.

“The existence of humanity on this planet is at risk because of climate change, so the announcement today is really a very, very powerful signal at the right moment,” said Patricia Espinosa, executive secretary at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, which organizes COP meetings.

As part of the Paris climate agreement, which Saudi Arabia signed onto, countries must present plans setting targets for reducing emissions for the next decade.

Bin Salman showed an official letter to the forum audience confirming that the country had submitted its so-called “nationally determined contributions” toward global climate goals.

He said that the country would reduce emissions by 278 million tonnes of carbon dioxide by 2030, relative to a business-as-usual baseline.

The nation’s emissions would be between 741 million tonnes and 849 million tonnes that year, he said.

Comparing those figures with data from the Global Carbon Project shows that the actual emissions in 2030 might be 27 to 45 percent higher than in 2019.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

After more than a year of review, the National Security Bureau on Monday said it has completed a sweeping declassification of political archives from the Martial Law period, transferring the full collection to the National Archives Administration under the National Development Council. The move marks another significant step in Taiwan’s long journey toward transitional justice. The newly opened files span the architecture of authoritarian control: internal security and loyalty investigations, intelligence and counterintelligence operations, exit and entry controls, overseas surveillance of Taiwan independence activists, and case materials related to sedition and rebellion charges. For academics of Taiwan’s White Terror era —

After 37 US lawmakers wrote to express concern over legislators’ stalling of critical budgets, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) pledged to make the Executive Yuan’s proposed NT$1.25 trillion (US$39.7 billion) special defense budget a top priority for legislative review. On Tuesday, it was finally listed on the legislator’s plenary agenda for Friday next week. The special defense budget was proposed by President William Lai’s (賴清德) administration in November last year to enhance the nation’s defense capabilities against external threats from China. However, the legislature, dominated by the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), repeatedly blocked its review. The

In her article in Foreign Affairs, “A Perfect Storm for Taiwan in 2026?,” Yun Sun (孫韻), director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said that the US has grown indifferent to Taiwan, contending that, since it has long been the fear of US intervention — and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) inability to prevail against US forces — that has deterred China from using force against Taiwan, this perceived indifference from the US could lead China to conclude that a window of opportunity for a Taiwan invasion has opened this year. Most notably, she observes that