When India went into lockdown in March last year and Tota Rai lost his cleaning job in the textile hub of Surat, he knew that working in the illegal mica mining industry back home was his only option.

Rai, 45, and his three sons — two adults and one teenager — now spend their days scavenging for scraps of the valued mineral, used to put the sparkle into cosmetics, car paint and electronics, to sell to local traders in eastern Jharkhand state.

However, as the COVID-19 pandemic drives more families to mica, residents, researchers and campaigners have voiced concerns over failings by the Indian government and private sector to regulate the often fatal trade sourced from abandoned mines and to create other jobs.

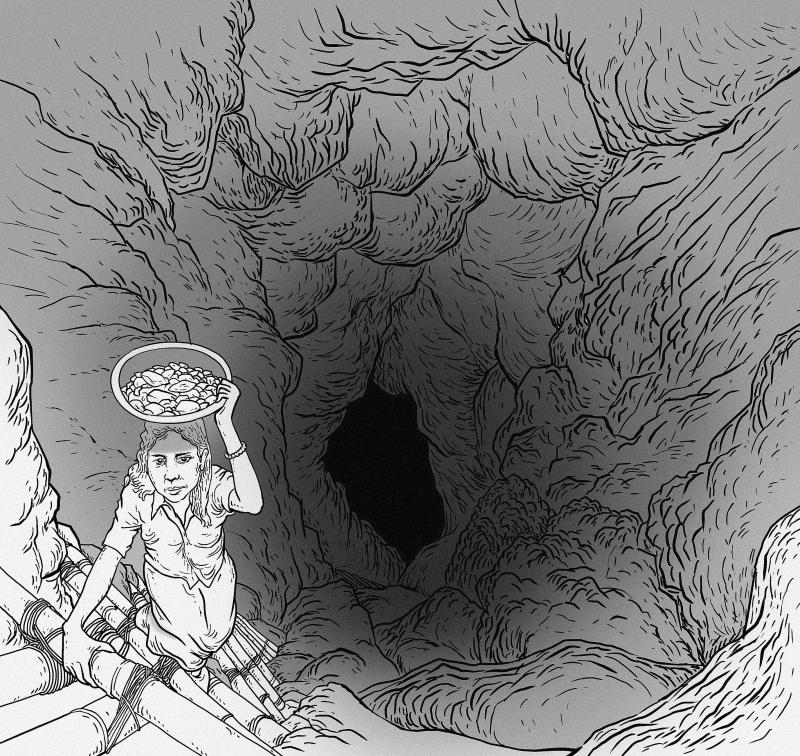

Illustration: Mountain People

A Thomson Reuters Foundation expose in 2016 found that the families of children who died in derelict mines in three Indian states were paid “blood money” to stay silent, prompting vows by brands to clean up supply chains, and authorities to legalize and regulate mica.

Rai said that his job as a hostel cleaner paid 5,000 rupees (US$68) monthly, but now he was fortunate to make 50 rupees a day selling mica gathered outside mines shuttered in the 1980s amid laws to limit deforestation and as alternatives to natural mica emerged.

“I reached home with great difficulty, but there was no other work here,” said Rai, who rode 2,000km on his bicycle over 10 days to return to his village in Giridih district, joining the ranks of millions of workers who headed home when COVID-19 struck India.

“Mica is our only hope to survive ... I just want to be allowed to pick mica,” he said by telephone from his mud hut in a region where even the roadside soil glitters with the mineral.

The Jharkhand government said that action was underway to legalize the sector, but progress had been slower than hoped.

K. Srinivasan, a secretary in the Jharkhand Department of Mines and Geology, said that a new policy was in the pipeline to “initiate mica mining legally” in the state and ensure jobs.

“We genuinely want to solve the problem,” he said.

India is one of the world’s top producers of mica. Once boasting more than 700 mines with more than 20,000 workers, the industry was hit by 1980s legislation to limit deforestation and the discovery of substitutes for natural mica — forcing most mines to close due to cost and stringent environmental rules.

Renewed interest in mica from China’s economic boom and a global craze for natural cosmetics in the past few years saw illegal operators reopen abandoned mines, creating a lucrative black market, but sometimes with tragic results.

Despite the dangers, Rai said that there was no choice but to pick mica.

After returning home in August, he joined a mica workers’ collective set up by local officials to help people find work through state schemes, but only secured eight days of work in four months, and his pay was delayed — which drove him back to mica.

“There is nothing here except mica ... all the children in my village go to collect mica,” he said.

A follow-up investigation by the Thomson Reuters Foundation in 2019 found that adults and children were still dying in the mines, with the global attention making people less likely to report deaths for fear of arrest or losing their earnings.

Traders and campaigners in two mica-rich districts in Jharkhand — Giridih and Koderma — estimate that thousands of people last year joined the ranks of about 50,000 mica miners and pickers due to job losses and school closures caused by the pandemic.

“People at the lowest level of the mica supply chain are children and the poorest of the poor, often with no land holding,” said Bhuwan Ribhu, a children rights activist who has worked for years with mica-dependent communities in Jharkhand.

Due to COVID-19, “their debts have increased, and we are worried that it might lead to a bonded labor situation,” he said, referring to people taking out loans from money lenders at high interest rates, a practice known to fuel modern slavery.

Activists and academics said that the pandemic had exposed the slow pace and limited scope of promised reforms by the Jharkhand government and the Responsible Mica Initiative (RMI), set up in 2016 to end child labor and improve conditions in mica mines.

The state government and the RMI have been criticized for focusing on modest community-level measures at the expense of pushing to legalize the sector and create alternative jobs.

“The policies [of the RMI and Jharkhand government] were limited to withdrawing children from mines,” said Sanjai Bhatt, a professor at the Delhi School of Social Work, who over the past decade researched mica-dependency in villages in Jharkhand.

“Livelihood was seen as a separate problem. There was no connection,” he said. “The RMI is a good, but toothless initiative in that regard ... of bringing about a policy change. And the government says it has offered jobs, but how many?”

The RMI, whose 60 or so members include cosmetics firm L’Oreal and drugs and chemical group Merck, raised about 880,000 euros (US$1.08 million) last year — down 30,000 euros from 2019 — to fund projects in dozens of villages across India’s mica belt.

The Paris-based coalition said it has put hundreds of children back in schools, and helped families find other sources of income and get connected to state welfare schemes.

“It’s a shared responsibility,” RMI executive director Fanny Fremont said, adding that governments, charities and companies needed to work together to “implement solutions with long-lasting impacts.”

The Thomson Reuters Foundation questioned several RMI brands such as L’Oreal, Merck and Porsche, which joined the initiative last year, about mica mining in Jharkhand and their own financial contributions.

L’Oreal and Merck said they were aware of unsafe conditions and the risk of child labor, but continued to source Indian mica so as not to “further weaken the situation in the region.”

Porsche, a subsidiary of Germany’s biggest automaker Volkswagen, did not respond to request for comment.

The RMI last year announced a sustainable mica mining policy that aimed to create jobs for 210,000 workers in Jharkhand and boost exports from this year, but two state government officials said that the plan was not feasible while the industry was still illegal.

Srinivasan said that regulating the industry required investment from the private sector, and past attempts to sell mica blocks to mining firms in 2018 and 2019 failed, with traders blaming the high price of 50 million rupees. No auction was held last year.

Srinivasan said that Jharkhand officials were now considering “ways to modify the bid price” for the blocks.

The Jharkhand Department of Women, Child Development and Social Security said it ensured that children received schooling from home during the pandemic with lessons broadcast on loudspeakers, adding that district offices were informed of human trafficking risks.

In Mansadi, a village in Giridih, community leader Anasiah Hembrom said that school attendance and literacy rates in the past few years improved, but COVID-19 had resulted in more children and returning migrant workers picking mica to earn a living.

Some returnees have found work under a rural government job scheme, but demand has far outstripped supply and issues such as delayed payments mean that many people have dropped out, he said.

“Mica promises guaranteed income at the end of a day’s work,” Hembrom said by telephone, but added that the price of mica from traders had last year more than halved to 5 rupees per kilogram.

Meanwhile, people are continuing to die in the mines.

Giridih police recorded two mica mine accidents last year — in March and November — that resulted in seven deaths. In both cases, police did not find the bodies, but recorded the deaths based on testimonies of villagers and visits to the mica mines.

For campaigners, the solution is clear: regulate the trade.

“The number of people mining mica has increased,” said Om Prakash, director of the Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation, which works with the state government to end child labor in mines.

“That is why it is important that people get the permission to mine legally, since it is the only livelihood option,” Prakash said.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.