A new national campaign against food waste has sparked a rare bout of speculation over Beijing’s ability to safely feed 1.4 billion Chinese when faced with floods, epidemics, locusts and rising tensions with some of its biggest trading partners.

The sudden and massive push to curb the problem of discarded leftovers — known as the “Clean Plates Campaign” — has puzzled experts who keep a close watch on the world’s biggest consumer of everything from grains to meat.

Chinese government officials have stressed that the country’s food reserves are ample, but some observers nevertheless questioned the timing of a campaign aimed at reducing consumption when China’s economy is still recovering from the effects of COVID-19.

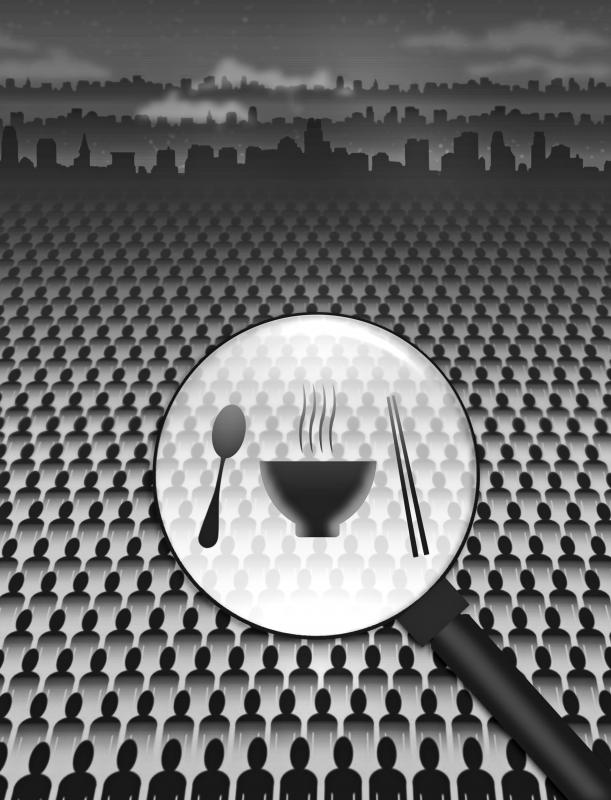

Illustration: Yusha

Bloomberg this week spoke with almost a dozen agricultural traders, food company officials and industry researchers about the initiative, the majority of whom said they believed the push was targeted at reducing dependence on food imports in preparation for possible supply disruptions. The Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

“Fears of supply disruptions due to COVID-19 have caused China’s leaders to re-emphasize food security and self-sufficiency,” StoneX senior Asia commodity analyst Darin Friedrichs said. “This includes diversifying where grain is sourced from abroad, but also making efforts to reduce food waste domestically.”

Political tensions have threatened trade flows in some market segments, and earlier this year, national governments started reducing exports and safeguarding local supplies because of worries over the COVID-19 pandemic — limiting the availability of food shipments to other countries.

Heavily reliant on protein imports to feed its people, concerns about breaks in the global food supply chain are particularly salient for China, whose leaders have long made economic development and personal enrichment a centerpiece of their rule.

The world could be facing “multiple famines of biblical proportions within a short few months,” World Food Programme Executive Director David Beasley said in April, citing the impact of the pandemic as well as more frequent natural disasters and changing weather patterns.

MASSIVE FLOODING

Biblical developments have contributed to concerns over China’s food supply this year. The country’s southern provinces have experienced massive flooding and swarms of locusts. Pork prices are beginning to tick up, even as China attempts to rebuild its supply of pigs after an outbreak of African swine fever-devastated herds, contributing to an overall jump in food inflation.

Fears that imported goods might be contaminated by COVID-19 have added to the pressure, with the southern city of Guangzhou ordering cold storage companies to suspend imports of frozen meat and seafood from pandemic-hit regions after the local government in nearby Shenzhen discovered COVID-19 on chicken wings imported from Brazil.

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) push to tackle the “shocking and distressing” problem of discarded leftovers has been swift and intense, with the national legislature scheduled to fast-track new rules as part of the effort. Livestreamers who film themselves eating huge amounts of food have been censured, while catering associations have urged restaurants to put limits on the number of dishes patrons can order.

Xi has been encouraging his country to build up its domestic economic strength in the face of intensifying external risks, including rising tensions with the US. Some veteran China experts believe the food waste campaign, launched on Aug. 11, is part of a similar long-term effort to increase food self-sufficiency.

Chinese Minister of Agriculture Han Changfu (韓長賦) this month stressedthe importance of keeping the people’s rice bowl filled with locally grown grain.

The campaign suggests that Beijing has started preparing for a theoretical worst-case scenario of a food supply shortage, three of the people surveyed by Bloomberg said. They asked to remain anonymous given the topic’s sensitivity in a country where food holds pride of place in many homes, and where memories of the Great Famine under former Chinese leader Mao Zedong (毛澤東) still linger.

“Food security is an important foundation for state security. Food wastage appears to be about individual behavior, but it could lead to extensive perils,” a People’s Daily analysis said last week.

About 35 million tonnes of food are wasted in China every year, representing almost 6 percent of its total output, the analysis said, adding that food supply in China would be tightly balanced for an extended period given rising costs, limited resources and solid demand.

China’s rapid economic development has drastically altered the nation’s food needs, with residents in cosmopolitan coastal provinces demanding ever more meat, chocolate, wine and coffee. That has contributed to skyrocketing consumption of animal feed, and dramatically increased China’s dependence on foreign crops including US soybeans, Australian barley and African cocoa and coffee beans.

So far, there is no sign that China has been procuring less food from overseas. Imports of farm products have been growing fast this year, with purchases of US corn and soybeans accelerating in the past few months. China has also boosted this year’s estimate for soybean imports to a record of 96 million tonnes, citing strong demand for protein-rich soybean meal for animal feed.

BILATERAL TENSIONS

However, rising political tensions between China and the US threaten to derail future orders, or force China to boost procurement from other trading partners at a time of uncertainty.

US exports of agricultural and related products to China in the first two quarters reached about 20 percent of this year’s target of US$36.5 billion agreed under the US-China phase one trade deal, even as the shipments were 6.3 percent higher year-on-year, according to US Department of Agriculture data.

China also halted some beef imports from Australia, and in May placed tariffs on the country’s barley shipments following the conclusion of an earlier anti-dumping probe. The Chinese embassy in Canberra in April said that Chinese consumers might choose to boycott Australian goods.

“In the context of the Great Decoupling, Beijing will, where possible, buy from countries in its sphere of political and economic influence,” Enodo Economics chief economist Diana Choyleva wrote in a report published earlier this month, noting that China’s large grain reserves were likely “overstated.”

A spokesman for the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics said at a press conference this month that the country has relatively sufficient grain stocks due to bumper harvests over the past five years. Grains harvested this summer — which include wheat and early rice — have increased by 0.9 percent year-on-year to a new record despite the floods, the spokesman said. Grains harvested in the fall account for over 70 percent of the nation’s total production and should be unscathed by the summer flooding, he added

While the intrusiveness of Xi’s anti-food waste campaign has led to it being dissected and occasionally criticized on social media, some have interpreted the move as a simple reminder to avoid unnecessary excess. Two industry executives interviewed by Bloomberg said that the campaign was a continuation of policies to reduce waste going back to at least 2013.

Meanwhile, the Chinese state-run Global Times has rejected the “media hype” and suggestions that the campaign might be connected to a looming food shortage, saying that it is merely about “an issue that deserves more attention.”

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

On today’s page, Masahiro Matsumura, a professor of international politics and national security at St Andrew’s University in Osaka, questions the viability and advisability of the government’s proposed “T-Dome” missile defense system. Matsumura writes that Taiwan’s military budget would be better allocated elsewhere, and cautions against the temptation to allow politics to trump strategic sense. What he does not do is question whether Taiwan needs to increase its defense capabilities. “Given the accelerating pace of Beijing’s military buildup and political coercion ... [Taiwan] cannot afford inaction,” he writes. A rational, robust debate over the specifics, not the scale or the necessity,