Thousands of Central American migrants trudging through Mexico toward the US have regularly been described as either fleeing gang violence or extreme poverty, but another crucial driving factor behind the migrant caravan has been harder to grasp: climate change.

Most members of the migrant caravans come from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador — three countries devastated by violence, organized crime and systemic corruption, the roots of which can be traced back to the region’s cold war conflicts.

Experts say that alongside those factors, climate change in the region is exacerbating — and sometimes causing — a miasma of other problems, including crop failures and poverty.

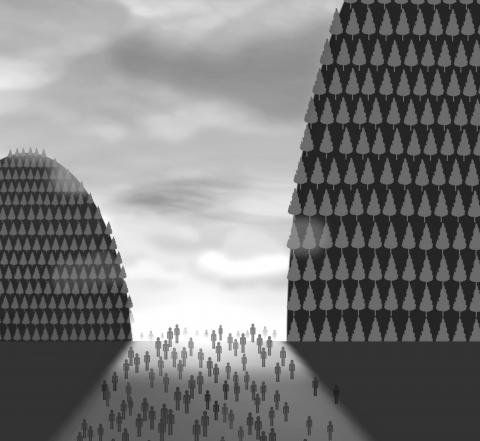

Illustration: Yusha

They also warn that in the coming decades, it is likely to push millions more people north toward the US.

“The focus on violence is eclipsing the big picture, which is that people are saying they are moving because of some version of food insecurity,” said Robert Albro, a researcher at the Center for Latin American and Latino Studies at American University.

“The main reason people are moving is because they don’t have anything to eat. This has a strong link to climate change — we are seeing tremendous climate instability that is radically changing food security in the region,” Albro said.

Migrants do not often specifically mention “climate change” as a motivating factor for leaving, because the concept is so abstract and long-term, Albro said.

However, people in the region who depend on small farms are painfully aware of changes to weather patterns that can ruin crops and decimate incomes.

Pausing for a rest as the first of the three recent migrant caravans passed through the Mexican town of Huixtla last week, Jesus Canan described how he used to sow corn and beans on a hectare of land near the ancient Copan ruins in western Honduras.

An indigenous Ch’orti’ Maya, Canan abandoned his lands this year after repeated crop failures, which he attributed to drought and changing weather patterns.

“It didn’t rain this year. Last year it didn’t rain,” he said softly. “My corn field didn’t produce a thing. With my expenses, everything we invested, we didn’t have any earnings. There was no harvest.”

Desperate and dreaming of the US, Canan hit the road early last month and joined the migrant caravan. He left behind a wife and three children — ages 16, 14 and 11 — who were forced to abandon school because Canan could not afford to pay for their supplies.

“It wasn’t the same before. This is forcing us to emigrate,” he said. “In past years, it rained on time. My plants produced, but there’s no longer any pattern [to the weather].”

US Customs and Border Patrol data show a surge in outward migration from western Honduras, a prime coffee-producing area, said Stephanie Leutert, an expert in Central American migration and security at the University of Texas.

Many of those are farmers or agricultural workers who take to the road when coffee growing is no longer profitable — such as Antonio Lara, 25, from the city of Ocotepeque, Honduras, who joined the caravan with his wife and children, aged six and 18 months.

“Coffee used to be worth something, but it’s been seven years since there was a decent price,” he said.

Lara said he thought that changing weather patterns had a lot to do with the problem, although he also blamed his plight on greedy bosses and coffee dealers.

“I didn’t leave my country because I wanted to. I left because I had to,” he said.

A third of all employment in Central America is linked to agriculture, so any disruption to farming practices can have devastating consequences. Since about 2012, coffee plants across Central America have been ravaged by an epidemic called leaf rust, which according to some estimates has affected 70 percent of farms.

Normally, the fungus dies when temperatures drop in the evening, but warmer nights are allowing it to thrive, said Sam Dupre, a researcher at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

The effect of climate change on the fungus is being debated, but Dupre said the situation in Guatemala “shows even without a direct climate change link what happens when these global commodities fail.”

“One of the things I found was that people, largely because they weren’t able to pay their debts, to get money for food, they started to migrate,” Dupre said. “People were telling me before the coffee leaf rust hit, we didn’t migrate. Now we do. It’s normal.”

A study of Central American migrants by the UN World Food Program last year found that nearly half described themselves as food insecure. The research found an increasing trend of young people moving as a result of knock-on poverty and lack of work.

Climate change is bringing more extreme and unpredictable weather to the region: Summer rainfall is starting later and has become more irregular. Drought fueled by El Nino has gripped much of Central America over the past four years, but the period has been occasionally punctuated by disastrous flooding rains.

As a result, more than 3 million people have struggled to feed themselves.

“Coffee and corn are sensitive to temperature and rainfall changes,” Albro said. “If a coffee crop fails you can’t just turn on a dime and do something else, it takes a long time to recover. There have been several lost crops in a row and it’s caused tremendous hardship for small-scale farming.”

Farmers first migrate to urban areas, where they confront a new set of problems, which in turn prompt them to consider an international odyssey.

“There’s an internal movement where someone will go to, say, Guatemala City and then perhaps get extorted by a gang and then move to the US,” Leutert said. “When they get here they will say they’ve moved because of violence, but climate change was the exacerbating factor.”

More than 50,000 Guatemalan families were apprehended trying to cross the US border in the first 10 months of the year, double the number of the previous year, US Customs and Border Protection said.

People move for a tangle of different reasons, and climate change’s influence is often far-reaching and hard to measure, but the World Bank estimates that warming temperatures and extreme weather will force an estimated 3.9 million climate migrants to flee Central America in the next 30 years.

This mass movement of people risks destabilizing their home countries and presents a challenge for destinations such as the US.

The 1951 UN refugee convention sets out clear criteria for the granting of asylum, such as persecution and war, but climate change is not on the list.

With an estimated 150 million to 300 million climate refugees set to be displaced worldwide by 2050, a new international framework will be needed to accommodate them.

“If your farm has been dried to a crisp or your home has been inundated with water and you’re fleeing for your life, you’re not much different from any other refugee,” said Michael Doyle, an international relations scholar at Columbia University. “The problem is that other refugees fleeing war qualify for that status, while you don’t.”

Doyle is part of a group of academics and advocates pushing for a new treaty that would focus on the needs of displaced people, rather than their exact reason for leaving, in order to cover the expected wave of climate migrants.

Any reform of the landmark refugee agreement is “quite unlikely at present,” Doyle said, due to the complexity of such a new arrangement, as well as the rise of nationalist governments in places such as the US.

“The president of the US is using migrant caravans as a political wedge issue as a way to get elected,” Doyle said. “If we reopen the 1951 convention, it’s more likely to be weakened than strengthened. We aren’t in a state where reforms, however sensible, can be made. There just isn’t the global statesmanship at the moment, nowhere near it.”

A failure by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to respond to Israel’s brilliant 12-day (June 12-23) bombing and special operations war against Iran, topped by US President Donald Trump’s ordering the June 21 bombing of Iranian deep underground nuclear weapons fuel processing sites, has been noted by some as demonstrating a profound lack of resolve, even “impotence,” by China. However, this would be a dangerous underestimation of CCP ambitions and its broader and more profound military response to the Trump Administration — a challenge that includes an acceleration of its strategies to assist nuclear proxy states, and developing a wide array

Eating at a breakfast shop the other day, I turned to an old man sitting at the table next to mine. “Hey, did you hear that the Legislative Yuan passed a bill to give everyone NT$10,000 [US$340]?” I said, pointing to a newspaper headline. The old man cursed, then said: “Yeah, the Chinese Nationalist Party [KMT] canceled the NT$100 billion subsidy for Taiwan Power Co and announced they would give everyone NT$10,000 instead. “Nice. Now they are saying that if electricity prices go up, we can just use that cash to pay for it,” he said. “I have no time for drivel like

Twenty-four Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers are facing recall votes on Saturday, prompting nearly all KMT officials and lawmakers to rally their supporters over the past weekend, urging them to vote “no” in a bid to retain their seats and preserve the KMT’s majority in the Legislative Yuan. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which had largely kept its distance from the civic recall campaigns, earlier this month instructed its officials and staff to support the recall groups in a final push to protect the nation. The justification for the recalls has increasingly been framed as a “resistance” movement against China and

Jaw Shaw-kong (趙少康), former chairman of Broadcasting Corp of China and leader of the “blue fighters,” recently announced that he had canned his trip to east Africa, and he would stay in Taiwan for the recall vote on Saturday. He added that he hoped “his friends in the blue camp would follow his lead.” His statement is quite interesting for a few reasons. Jaw had been criticized following media reports that he would be traveling in east Africa during the recall vote. While he decided to stay in Taiwan after drawing a lot of flak, his hesitation says it all: If