“Nowadays, nobody speaks much Patua. Only the old people speak Patua,” 102-year-old Aida de Jesus said as she sat across the table from her daughter inside Riquexo, the small Macanese restaurant that she runs to this day despite her grand age.

Patua is the name of De Jesus’ mother tongue and she is one of its last surviving custodians.

Known to those who speak it as “Maquista,” Patua is a creole language that developed in Malacca, Portugal’s main base in southeast Asia, during the first half of the 16th century and made its way to Macau when the Portuguese settled there.

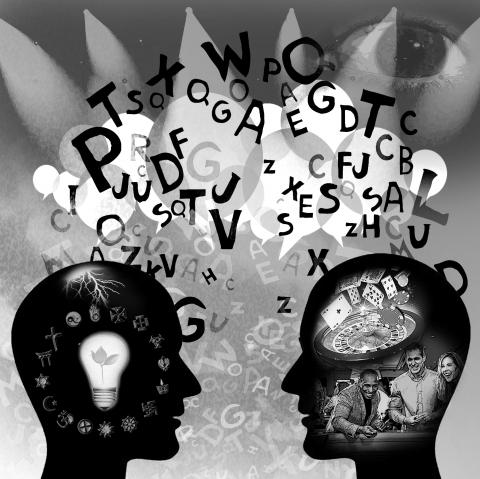

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

It blends Portuguese with Cantonese and Malay, and some traces of other languages from stops on the Portuguese trading route.

Patua developed to eventually become the language of Macau’s indigenous Eurasian community: the Macanese. They first arose from intermarriages between Portuguese colonizers and the Chinese — mostly Portuguese men marrying and starting families with Chinese women.

However, as of the second quarter of the 19th century, the strengthening of public education in Portuguese and the socio-economic advantages associated with the language led to the stigmatization of Patua. It was shunned as “broken Portuguese” and became a language confined mostly to the home.

In 2009, UNESCO classified Patua as a “critically endangered” language and as of the year 2000, there were estimated to be just 50 Patua speakers worldwide.

“At school, I was taught Portuguese and told not to speak Patua” De Jesus said. “If I spoke Patua at school, they would not understand, and so we had to speak Portuguese.”

Elisabela Larrea, a part-time PhD student and author of a blog that introduces Patua dialect flashcards to English and Chinese readers, learned of the challenges her ancestors faced speaking the language. She is now part of a small community in Macau that wants to help preserve it as a medium of Macanese culture.

“My mother once told me: ‘Our parents gave up what was ours for a language that is not; now we are left to grab back what truly represents our culture, our spirit. Patua is our language; it is ours,’” Larrea said.

“If you spoke in Patua you were seen as uneducated, so I can understand why parents, in the past, forbade children to learn their own Macanese language,” she said.

However, now “the Macanese are more proud of who they are compared to years ago, when Macanese culture was not held in high regard,” Larrea said.

This sea change has inspired efforts to revive the language.

Miguel de Senna Fernandes is a local lawyer and president of the board of the Macanese Association; he is also one of the main faces of the Patua revival.

Fernandes is director of Macau’s Patua language drama troupe, Doci Papiam di Macau, meaning “sweet language of Macau.” For more than 20 years, it has been preserving the language through original plays performed in Patua by local actors. The group’s work, presented with subtitles in English, Chinese and Portuguese, has become one of the most anticipated features at the annual Macau Arts Festival.

“When no one really speaks Patua anymore, people ask me: Why do we make all this fuss to write a play and engage so many people?” Fernandes said. “I say it’s like something that your dad left behind, like a jar or a notebook. You know that it belongs to one of your dearest, though you won’t likely use it — but you won’t throw it away because you feel connected to it. The same is true of Patua. We don’t speak it on a daily basis, it’s not useful anymore, but it links us to our ancestors and to a sense of our unique community.”

Since Macau was handed back to China in 1999, that distinct community and unique Macanese culture is again fighting to hold on. Macau has swelled into the world’s most successful gambling hub, with its booming casino industry accounting for about 80 percent of its economy.

While it has helped the city financially, this growth has done little to reflect Macau or its local culture. Instead, a number of local citizens say the favored strategy has been to copy and paste Las Vegas, casino resort by casino resort, with only one goal in mind: easy money.

“I think the casinos definitely could have tried harder to represent something local in Macau — something that will make tourists wonder and think about and discover Macau,” Fernandes said.

“Out of nowhere you have an Eiffel tower in Macau, a Venetian [hotel] in Macau and now they are building a mini-London. From our perspective, as culturally aware citizens, this is all rubbish — it says absolutely nothing about what Macau is,” he said.

Others, such as Larrea, said they feel that the work of promoting Macanese culture lies firmly with the community itself.

“I think the problem is that the Macanese don’t come out enough — it’s our responsibility,” she said. “We can’t just say: Why isn’t the government doing more or why aren’t the casinos doing more to promote our culture? We have to do it ourselves.”

One thing that brings consensus is that time is running out to save Patua — and indeed the Macanese community overall. With it facing larger cultural forces than ever before, the likelihood of extinction is inevitable, some believe.

“I think the Macanese community will die out,” Larrea said. “95 percent of Macau’s population is now Chinese. Even my husband is Chinese. So, if I have kids, I will try to pass on Macanese values to them, but I doubt that my grandchildren will even hear Patua. I think, three or four generations from now, the language will no longer be used.”

It is not just Macau’s local population that is majority Chinese. Of the city’s 30.95 million tourists in 2016, about 28 million came from the Chinese mainland.

“You just can’t ignore this mainland China absorption, because it’s everywhere and it’s daily,” Fernandes said. “Macau is so tiny. We used to say that if every Chinese from the mainland spat on Macau, we would be drowned. I think everyone has their own way to resist the absorption and the Macanese community by nature are survivors.”

However, as resilient as the Macanese are, Fernandes is only too aware of how “monolithic and exclusivist the Chinese culture can be,” he said.

It remains to be seen if the unique Macanese language and Eurasian community can resist being absorbed by Chinese influence for much longer.

Fernandes said he believes the resilient Macanese spirit will prevail and the community will survive for as long as it is able to hold on to a sense of what makes it unique.

“The old Macanese community will fade away, but the new generation of Macanese still has a sense of what makes them different — they know about their ancestry, they know about the Portuguese,” he said.

“How can you claim identity if you don’t feel different from the rest?” Fernandes asked. “So, fortunately, I see that the new generation of Macanese is aware of this and they are holding on. At least for now, I am optimistic.”

When US budget carrier Southwest Airlines last week announced a new partnership with China Airlines, Southwest’s social media were filled with comments from travelers excited by the new opportunity to visit China. Of course, China Airlines is not based in China, but in Taiwan, and the new partnership connects Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport with 30 cities across the US. At a time when China is increasing efforts on all fronts to falsely label Taiwan as “China” in all arenas, Taiwan does itself no favors by having its flagship carrier named China Airlines. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is eager to jump at

The muting of the line “I’m from Taiwan” (我台灣來欸), sung in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), during a performance at the closing ceremony of the World Masters Games in New Taipei City on May 31 has sparked a public outcry. The lyric from the well-known song All Eyes on Me (世界都看見) — originally written and performed by Taiwanese hip-hop group Nine One One (玖壹壹) — was muted twice, while the subtitles on the screen showed an alternate line, “we come here together” (阮作伙來欸), which was not sung. The song, performed at the ceremony by a cheerleading group, was the theme

Secretary of State Marco Rubio raised eyebrows recently when he declared the era of American unipolarity over. He described America’s unrivaled dominance of the international system as an anomaly that was created by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Now, he observed, the United States was returning to a more multipolar world where there are great powers in different parts of the planet. He pointed to China and Russia, as well as “rogue states like Iran and North Korea” as examples of countries the United States must contend with. This all begs the question:

In China, competition is fierce, and in many cases suppliers do not get paid on time. Rather than improving, the situation appears to be deteriorating. BYD Co, the world’s largest electric vehicle manufacturer by production volume, has gained notoriety for its harsh treatment of suppliers, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability. The case also highlights the decline of China’s business environment, and the growing risk of a cascading wave of corporate failures. BYD generally does not follow China’s Negotiable Instruments Law when settling payments with suppliers. Instead the company has created its own proprietary supply chain finance system called the “D-chain,” through which