Chandrika Shenoy’s son, Mahesh, lies on the ground beside her on a mat, his limbs twitching as he moans, seemingly in distress.

Following a supreme court ruling last month, the family are waiting to receive the 500,000 rupees (US$7,455) the Government of Kerala, India, has been ordered to pay thousands of people whose lives have been permanently scarred by years of routine spraying of the cheap, highly toxic pesticide endosulfan.

“The compensation cannot give my son his childhood back,” said Shenoy from their home in Kasaragod, Kerala. “Or give me my life back. All it can do is help us provide him with the best care.”

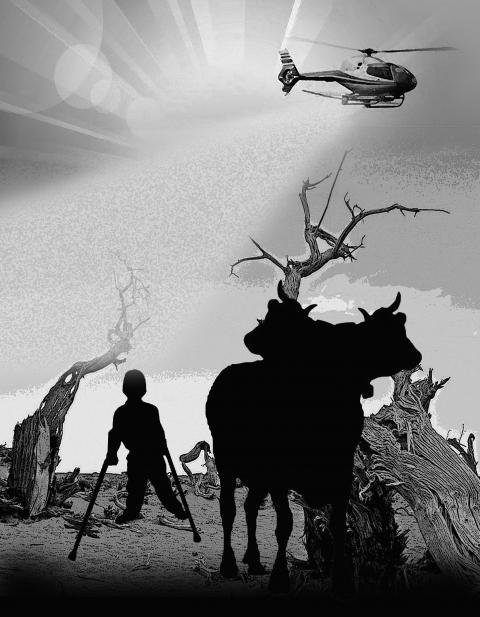

Illustration: Constance Chou

Her face bears the strain of caring for her son for 18 years. Shenoy knew instantly something was different about her son when he was born.

“Mahesh’s face and skin tone were beautiful, but his body structure was not right. He was dull and passive and slept all the time. When, at the age of three, he began to have fits that lasted all night, the doctors at Calicut Medical College said endosulfan was responsible for his condition,” she said.

His thick medical file says he has cerebral palsy with spastic quadriplegia.

Endosulfan is banned in 80 countries, but for more than 20 years, starting in 1973, it was sprayed from helicopters over a cashew crop in the lush, verdant landscape of this northernmost tip of Kerala three times a year.

Farmers heard helicopters roar over the cashew estates — a pleasing sound, as it meant their crops were protected against the tea mosquito bug. They called endosulfan marunnu, which means medicine.

The first symptoms of ill health, among humans and livestock, were detected in the 1990s. Farmers described seeing a pile of dead butterflies near a papaya tree and other insects dying in droves.

Frogs gobbled up the dead insects and died. Chickens that ate the frogs also died. Calves were born with twisted legs. One was born with two heads.

Among humans, doctors began noticing congenital disabilities, hydrocephalus, diseases of the nervous system, epilepsy, cerebral palsy and severe physical and mental disabilities. As activists exchanged notes, they realized these symptoms were confined to Kasaragod, the sole district where endosulfan was aerially sprayed.

In 2001, following protests, the Kerala State Pollution Control Board ordered the Plantation Corp of Kerala to stop aerial spraying.

That same year, a study by the Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi said its analysis strengthened the suspicion “that the Kerala pesticide tragedy is a government corporation’s creation.”

One woman’s blood showed 900 times the amount of endosulfan permitted in water.

In 2004, the High Court of Kerala banned the pesticide.

“It was too late,” Endosulfan Victims’ Support Aid Group founder MA Rahman said. “It had leached into the soil and water. No one told farmers to cover their wells during spraying. Children continued eating the cashew plant flower. Farmers would send cattle out to graze after the spraying.”

A 2008 report by the Kerala pollution board confirmed Rahman’s theory, showing the presence of endosulfan in water samples collected from sprayed areas.

Northern Kerala is full of bodies of water: lagoons, ponds, canals, open wells and 14 rivers. When it rained, the pesticide washed down the hills into the valleys and flatlands where people grew rice, vegetables and fruit for their own consumption.

Finally, in 2011, the supreme court banned endosulfan throughout India.

Activists have called the tragedy India’s “secret Bhopal” — a reference to the 1984 disaster when toxic gas leaked from the Union Carbide factory in Bhopal, India. Unlike Bhopal, where victims were concentrated in the shantytown around the factory, victims in Kerala were dispersed across tiny hamlets and the disaster is largely unknown outside the area.

Kasaragod resident Aisha Shakira lives in Adhur village with her two daughters.

Abida, 21, has mental health problems and has been bedridden since she was five. She has fits, but the frequency has reduced with treatment at Kerala’s Pariyaram Medical College.

Fatima, 15, smiles easily and is happy to pose for photographs, but does not comprehend anything.

When asked for her reaction to the Supreme Court ruling, Shakira shrugs.

“I suppose we can improve our house to make it nicer and more cheerful for my girls, but they lost their childhood and I have had no life. I can’t remember the last time I left the house. Weddings in the family, engagements, births, festivals — I had to miss them all. I can’t leave them alone for a minute,” she said.

A short distance away, the concern of Abu Bakr, a daily wage laborer, is for the future. His sons Ashiqi, 24, and Shafiq, 17, need constant attention.

Shafiq has cerebal palsy and requires 24-hour care. Ashiqi is slightly less physically challenged, but cannot function on his own.

They are lying on a bed in the neat and clean living room watching a TV serial with their father.

“What I need from the government is a basic income so that I don’t need to worry about working and can devote myself to the boys. My wife can’t lift them. I need to be around all the time. The compensation will only go so far,” he said.

The government plans to act on the court ruling soon. A huge medical camp with doctors from different specialties will be held in the first week of next month to finalize the list of casualties and sift through any possible false claims.

Jeevan Babu, district collector in Kasaragod, believes the final number is likely to be about 6,000 people.

“One gray area in the ruling is what level of disability warrants compensation. We need to figure that out, but we aim to err on the side of being generous,” he said.

When US budget carrier Southwest Airlines last week announced a new partnership with China Airlines, Southwest’s social media were filled with comments from travelers excited by the new opportunity to visit China. Of course, China Airlines is not based in China, but in Taiwan, and the new partnership connects Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport with 30 cities across the US. At a time when China is increasing efforts on all fronts to falsely label Taiwan as “China” in all arenas, Taiwan does itself no favors by having its flagship carrier named China Airlines. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is eager to jump at

The muting of the line “I’m from Taiwan” (我台灣來欸), sung in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), during a performance at the closing ceremony of the World Masters Games in New Taipei City on May 31 has sparked a public outcry. The lyric from the well-known song All Eyes on Me (世界都看見) — originally written and performed by Taiwanese hip-hop group Nine One One (玖壹壹) — was muted twice, while the subtitles on the screen showed an alternate line, “we come here together” (阮作伙來欸), which was not sung. The song, performed at the ceremony by a cheerleading group, was the theme

Secretary of State Marco Rubio raised eyebrows recently when he declared the era of American unipolarity over. He described America’s unrivaled dominance of the international system as an anomaly that was created by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Now, he observed, the United States was returning to a more multipolar world where there are great powers in different parts of the planet. He pointed to China and Russia, as well as “rogue states like Iran and North Korea” as examples of countries the United States must contend with. This all begs the question:

In China, competition is fierce, and in many cases suppliers do not get paid on time. Rather than improving, the situation appears to be deteriorating. BYD Co, the world’s largest electric vehicle manufacturer by production volume, has gained notoriety for its harsh treatment of suppliers, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability. The case also highlights the decline of China’s business environment, and the growing risk of a cascading wave of corporate failures. BYD generally does not follow China’s Negotiable Instruments Law when settling payments with suppliers. Instead the company has created its own proprietary supply chain finance system called the “D-chain,” through which