For a long time, playing pickup basketball as an Asian-American guy involved the considerable likelihood that someone would call you Yao Ming (姚明).

Yao is Asian. You are Asian. That was the joke.

That formulation began to fade, though, about four years ago, when Jeremy Lin (林書豪), a Taiwanese-American point guard from Palo Alto, California, playing at the time for the New York Knicks, became a household name in a blinding, month-long metamorphosis still referred to today as Linsanity.

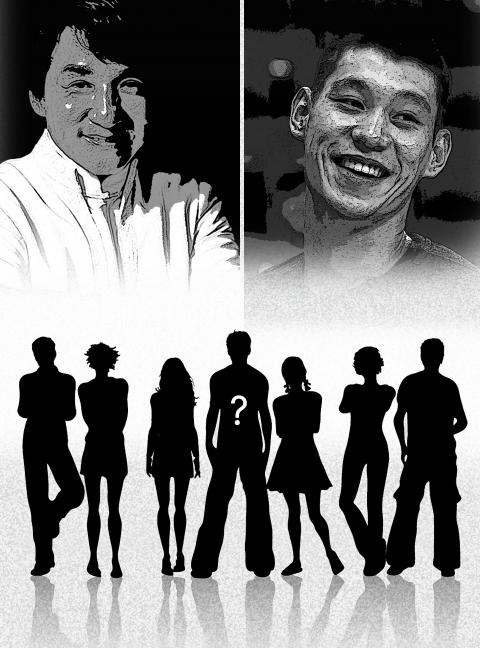

Illustration: Constance Chou

I felt things shift about two weeks into his rise. I was covering spring training baseball in Port St Lucie, Florida, that month for The New York Times. One afternoon, I drove to a public basketball court to find a game.

“Jeremy Lin is here,” someone announced.

At one point, I caught a pass on the move, juked to my left, then hopped to the basket for a layup.

“He’s nice like Lin, too,” somebody joked.

This is how it is going to be now, I guessed.

And I was right: Weeks later, back home in Manhattan, I held the door open for a man at a bank and instead of saying thank you — the two-word phrase we’re conditioned to expect in that situation — he looked at me and said: “Jeremy Lin.”

It is common as an Asian-American to feel like an unwilling participant in society’s lazy word-association game: See someone Asian, say something Asian.

An absence of reference points for Asian identity in popular culture has helped create a perpetual stream of hackneyed encounters, for men and women, children and adults.

“In elementary school, it was Jackie Chan (成龍),” my friend Daniel Sin, a fellow hoops addict and Korean-American, told me about playing pickup ball. “In high school, it was Yao Ming. At the gym now, it’s Jeremy Lin. When it first happened, around Linsanity, I thought: ‘Nice. At least I’m a guard now.’”

Lin has returned to the public eye in New York as he prepares to begin his first season as a member of the Brooklyn Nets. His narrative continues to resonate with Asian-Americans, in part, because of the way his skin color has shaped the substance of his life.

During a talk at the New Yorker festival this month, Lin recalled that as a little-known high-school basketball player he dreaded the moments before games when he knew he would hear those familiar taunts from people in the stands: “Yao Ming, Yao Ming.”

Nicknames on a court, of course, can be wielded with affection or respect, and rhetorical sparring can be one of basketball’s auxiliary pleasures.

However, as Ren Hsieh (謝仁), the Taiwanese-American commissioner of the Dynasty League, a recreational basketball organization in Chinatown, pointed out, the intent of words is usually pretty clear.

“I’m a 5-foot-9 [1.75m] point guard,” Hsieh said, laughing. “If you call me Yao Ming, I know what you’re saying.”

Lin might be too famous today for those proper-noun taunts, but he remains a magnet for abuse.

“Even now, to this day, you go to NBA arenas, guys will say racist things, ‘chicken lo mein’ or whatever, which is a really good dish, by the way, but I don’t like being called that,” Lin said at the New Yorker event.

Likewise: Jeremy Lin is a good player, but we do not like being called that.

Eddie Huang, a Taiwanese-American chef, writer, and television host, recalled an interaction three years ago, on St Patrick’s Day, in which a group of men emerged from a bar near his restaurant on 14th Street and shouted to him: “Yo, Jeremy Lin.”

Huang felt tempted to throw a punch before checking himself.

“I don’t want nobody calling me Jeremy, because it reminds me of being called Long Duk Dong or reminds me of being called things like Jackie when I was a kid,” Huang said. “I don’t like that. I’m Eddie Huang, you know what I mean?”

This was the landscape of Linsanity. Along with whatever euphoria Lin’s unexpected success engendered among Asians, we remember, too, all the residual messiness as people around us betrayed an inability, or a lack of desire, to treat him with basic decency.

As his name was added to the shortlist of famous Asian people invoked in racist taunts, it was an uncomfortable evidence again of the dearth of Asian representation in media and popular culture.

I started covering the NBA for this newspaper a year and a half after Linsanity — Lin was playing for the Houston Rockets at that point — and it took precisely three games for a stranger at an arena to call me Jeremy Lin.

I was leaving the visitors’ locker room that night in Orlando, where the Magic had just hosted the Nets. A big crowd of autograph seekers perked up as they sensed me approaching and deflated again when they realized who it was.

However, a second or two later, there it was: “It’s Jeremy Lin!” someone yelled, making the crowd laugh.

“That’s racist,” I said, halfheartedly.

“He said: ‘That’s racist!’” someone said, and everyone laughed again.

This is as good a time as any to write: If you think Lin and I look alike, you may be the type of person who thinks all Asian people look alike.

A few weeks later, I walked into the Nets’ locker room in Houston as they dressed to play the Rockets. Lin was on the injured list for Houston that night. Seeing me, one Nets player could not resist: “I thought Jeremy Lin was out tonight,” he said, feigning surprise.

I gave the player an incredulous stare.

He broke the silence.

“You aren’t going to tweet about that are you?” he said, suddenly serious.

Racism has far more dire consequences than asinine name-calling, but it will serve always as a barefaced reminder of the extent to which we remain alien in people’s minds.

Respite from this, realistically, feels far-off.

So you stare ahead. You laugh things off. You do not lash out because do you really want to spend your days lashing out?

You wait for another Yao Ming, another Jeremy Lin, and another, and another, until maybe the names begin to lose their meaning.

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

Heavy rains over the past week have overwhelmed southern and central Taiwan, with flooding, landslides, road closures, damage to property and the evacuations of thousands of people. Schools and offices were closed in some areas due to the deluge throughout the week. The heavy downpours brought by the southwest monsoon are a second blow to a region still recovering from last month’s Typhoon Danas. Strong winds and significant rain from the storm inflicted more than NT$2.6 billion (US$86.6 million) in agricultural losses, and damaged more than 23,000 roofs and a record high of nearly 2,500 utility poles, causing power outages. As

The greatest pressure Taiwan has faced in negotiations stems from its continuously growing trade surplus with the US. Taiwan’s trade surplus with the US reached an unprecedented high last year, surging by 54.6 percent from the previous year and placing it among the top six countries with which the US has a trade deficit. The figures became Washington’s primary reason for adopting its firm stance and demanding substantial concessions from Taipei, which put Taiwan at somewhat of a disadvantage at the negotiating table. Taiwan’s most crucial bargaining chip is undoubtedly its key position in the global semiconductor supply chain, which led