Tang Xili came to Japan in 2013, hoping to earn enough in three years to build a new home for her daughter. Instead, she ended up in a labor-union shelter, after leaving an employer she says owes her about ¥3.5 million (US$31,000) in unpaid wages.

The 35-year-old from Yizheng City in China said she worked long hours, six days a week, was paid less than the minimum-wage rate for her overtime, and could not change her employer because of the terms of her visa.

“I really regret coming to Japan,” she said at the shelter in Hashima, Gifu Prefecture, in central Japan, where she is staying in an effort to get her back wages. “I won’t recommend that my friends come here to suffer.”

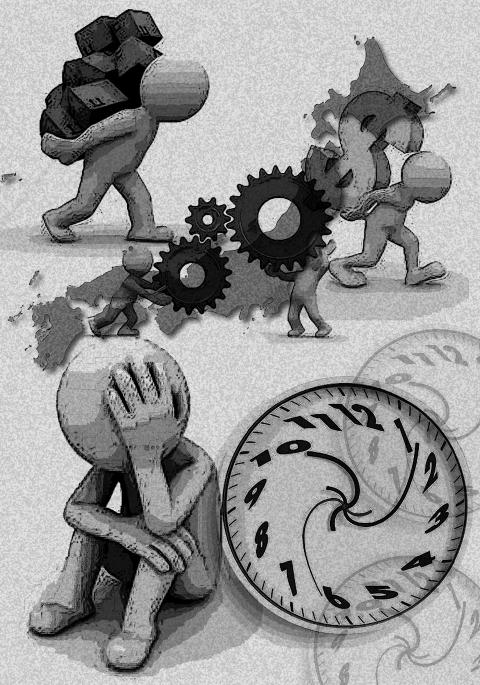

Illustration: Constance Chou

Tang is among more than 180,000 foreign workers in Japan who gained employment permits as part of a government program to train people from developing nations with skills they could use back home. Instead, the plan became a way for some Japanese companies to circumvent the nation’s strict foreign-labor rules and gain a supply of cheap workers, according to government documents and interviews with officials, employers and staff.

Tang’s former employer, Takara Seni, is a textile maker in Kagawa Prefecture in southern Japan. Managing director Yoshihiro Masago declined to discuss Tang’s position, but said his company needs the overseas workers.

“We can’t make it with Japanese alone,” he said in a telephone interview. “We can’t fill openings when we advertise them.”

Masago wants Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to create a proper immigration program for foreign workers to do low-paid and semi-skilled work. Abe, who just lost his economy minister over a graft scandal and is struggling to lift inflation from near zero, is unlikely to tackle that task.

“Abe’s administration isn’t pursuing an immigration policy,” said Kazuteru Tagaya, professor of law at Dokkyo University in Saitama Prefecture, who chaired a panel of experts to overhaul the so-called Technical Intern Training Program. “It’s a taboo because of the premise that Japan is racially homogeneous. A majority of the general public won’t accept it.”

Instead, to counter Japan’s shrinking workforce and high wages, Abe’s administration plans to extend the intern system, a back door into the country’s labor market that has seen increasing accusations of abuse. A bill in parliament aims to extend the program to five years from three and create a new watchdog to prevent exploitation of trainees.

The bill would require domestic agencies to obtain a permit, while the watchdog would review training plans for interns, keep track of companies using the program and investigate potential abuses. The bill also aims to define what constitutes “human rights violations against trainees” and decide on penalties for such violations as well as helping interns with consultation and information.

Tagaya, 67, is concerned that, without proper oversight, an expanded program would lead to continued abuses that include some companies paying agencies to supply workers and in effect deducting the costs from the workers’ wages.

“We can no longer let it go rampant when it’s being used for what appears to be human trafficking,” he said.

Some workers in the program “experience conditions of forced labor,” the US Department of State said in July last year’s Trafficking in Persons Report, which covers countries around the world. Japan has never identified a victim, “despite substantial evidence of trafficking indicators, including debt bondage, passport confiscation and confinement,” the report said.

The US report said some interns “pay up to US$10,000 for jobs and are employed under contracts that mandate forfeiture of the equivalent of thousands of dollars if workers try to leave.” There were reports of excessive fees, deposits, and “punishment” contracts, the State Department said.

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime says human trafficking is the acquisition of people by improper means such as force, fraud or deception, with the aim of exploiting them, while the UN says forced labor can involve “migrants trapped in debt bondage.”

Documents from Japan’s Labor Ministry, Justice Ministry and the government panel appointed to examine the program cite cases of companies paying less than the minimum wage, demanding deposits from workers and confiscating passports and mobile phones.

“Current regulations don’t work,” Tagaya said. “We have to tighten the legal framework.”

The number of interns has grown about 20 percent in the two-and-a-half years through June last year, according to the Japanese Ministry of Justice.

“The reality is, a lot of those who come for training work under poor labor conditions rather than as real trainees,” Shigeru Ishiba, Japan’s minister of regional revitalization, said in an interview on Jan. 25. “Before you talk about immigration policy, you first need to correct their treatment.”

The program, started in 1993, recruits trainees for 72 occupations in areas such as agriculture, fishing, construction, food processing and textiles. They erect scaffolding, stuff sausages and make cardboard boxes, among much else. In most cases, agencies in Japan and abroad match workers with companies. As of January last year, 31,320 companies used the program, according to the ministry.

Tang said she paid a recruiting agency in China more than 30,000 yuan (US$4,600) to find a place for her after it promised she would come home with savings of ¥5 million. She left her daughter, now 9, behind and joined about 30 Chinese trainees at Takara Seni.

On weekdays, they worked from 7am to 8:35pm with an hour break, Tang said.

Hourly pay was ¥700 for nine hours of the day during the week — around the minimum-wage rate — with overtime and Saturdays paid at ¥400 per hour, she said.

In a dormitory with up to five to a room, workers had the chance to earn extra money doing piecework, sewing buttons and cleaning lint, sometimes until 2am, she said.

Tang said she was earning about ¥140,000 per month after her employer subtracted rent, utilities, benefits and Internet service. While that is twice what she got in her hometown of Yizheng, it was also double the work hours. She said her boss banned her and colleagues from having a mobile phone and held their bankbooks when they visited home, preventing them from gaining access to their money.

Masago, the managing director, said it is getting harder to recruit Chinese workers with the minimum wage, but it is difficult to raise wages because of competition from cheap imported garments.

“They should be allowed to come as unskilled workers” as part of a proper immigration program, he said. “They come 100 percent for money. Japan lacks people. That is the only mutual interest.”

Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare investigated 3,918 companies with trainees and found 76 percent of them broke labor rules in 2014. Violations included an hourly pay of ¥310 per hour — less than half the national average minimum wage — 120 overtime hours in a month, compared with 45 allowed under the law, and the use of unsafe machinery. It did not identify the companies.

In 2014, the Japanese Ministry of Justice banned 241 agencies and companies from accepting trainees for up to five years for violations.

The Japan International Training Cooperation Organization, which is partly funded by membership fees from recruiting agencies, often warns employers before inspecting them and has no authority to punish violations, according to Akira Oike, a manager in the organization’s planning and coordination division.

He declined to comment on abuse or exploitation of trainees.

With tales of hardship from former interns and rising wages in China, the number of Chinese trainees has fallen 14 percent to 96,120 during the two-and-a-half years to June last year, according to the Ministry of Justice.

In Beijing, average monthly pay was 6,463 yuan in 2014, compared with about ¥124,800 per month for an eight-hour day in Japan at the national average minimum wage. The yen’s 21 percent plunge versus the yuan since Abe took office in late 2012 has cut the value of wages in Japan when repatriated to China.

That has led some Japanese employers to seek recruits in Vietnam, the Philippines and Indonesia.

TSS Co, a maker of industrial machinery, accepted six trainees from Vietnam last year for the first time. It employs eight Chinese women with its group firm Toyama Seikensha Co, according to Nobuyuki Arakawa, manager at TSS. They work on production lines in Toyama Prefecture in central Japan.

The two companies follow the rules and spend about ¥200,000 per month per trainee to cover base salary, overtime and agency fees, he said, adding that it is hard to promote interns, because they will only be with the company until their three-year visa expires.

“We want to invest in people who are committed to stay medium-to-long term,” Arakawa, 35, said. “If they stay only for three years, we cannot make that investment.”

While the proposed changes may extend that to five years, they would not allow trainees to change jobs freely.

“It is telling these people to shut up and work even if they get paid ¥300 per hour, even if they are sexually harassed,” said Shoichi Ibusuki, a Tokyo-based lawyer who supports troubled trainees.

He said many cannot leave because they borrowed money to pay agency fees to get the job. “If they can’t recover at least their initial investment, all they have will be debt.”

Even so, many flee. In 2014, 4,847 trainees went missing — almost two thirds of them Chinese — and last year’s total is expected to increase, according to the Ministry of Justice.

Last month, Tang and eight other Chinese workers were staying in the shelter in a run-down part of Hashima, which calls itself “Textile Town.” Zhang Wenkun, 36, had been there for months. He worked at Nobe Kogyo, a construction-waste recycling firm in Tochigi Prefecture, north of Tokyo, and had his hand injured by a wood grinder.

He said he received insurance payments while he was off work for three months recovering. However, when he returned to work his hand began to hurt again and the company threw out his belongings and told him to quit, he said.

“The program is a big failure,” Zhang said, showing his scarred wrist. “It’s dead and meaningless.”

Three of his former colleagues went missing from their jobs, said Zhang, who used to work in Dalian, China. One of them, Lin Xijun said he fled because his Japanese colleagues bullied him. He held temporary jobs hiding his identity in Japan, before making his way back to China, almost broke. He paid more than 60,000 yuan to an agency to come to Japan.

“They ruined my dream,” he said by telephone from Wafangdian, a suburb of Dalian. “Reality turned out to be much more cruel.”

Nobe Kogyo, the company Zhang worked for, declined an interview request and would not comment on the accusations.

Motohiro Onda, who works for the labor standards bureau at the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, would not say whether there was an investigation into Takara Seni or Nobe Kogyo, because the bureau does not disclose information about individual cases.

Industry in Hashima, the town where Tang is staying at the shelter, has been hollowed out as overseas competition caused mills to shut down. If it is going to survive, Japan needs to change its attitude toward foreign workers, Hashima Mayor Satoshi Matsui said.

“We need to have people willing to work hard with us in the global society,” Matsui, 64, said. “We need to make our community a place where those people can live with us, rather than huddling in their own group.”

Labubu, an elf-like plush toy with pointy ears and nine serrated teeth, has become a global sensation, worn by celebrities including Rihanna and Dua Lipa. These dolls are sold out in stores from Singapore to London; a human-sized version recently fetched a whopping US$150,000 at an auction in Beijing. With all the social media buzz, it is worth asking if we are witnessing the rise of a new-age collectible, or whether Labubu is a mere fad destined to fade. Investors certainly want to know. Pop Mart International Group Ltd, the Chinese manufacturer behind this trendy toy, has rallied 178 percent

My youngest son attends a university in Taipei. Throughout the past two years, whenever I have brought him his luggage or picked him up for the end of a semester or the start of a break, I have stayed at a hotel near his campus. In doing so, I have noticed a strange phenomenon: The hotel’s TV contained an unusual number of Chinese channels, filled with accents that would make a person feel as if they are in China. It is quite exhausting. A few days ago, while staying in the hotel, I found that of the 50 available TV channels,

There is no such thing as a “silicon shield.” This trope has gained traction in the world of Taiwanese news, likely with the best intentions. Anything that breaks the China-controlled narrative that Taiwan is doomed to be conquered is welcome, but after observing its rise in recent months, I now believe that the “silicon shield” is a myth — one that is ultimately working against Taiwan. The basic silicon shield idea is that the world, particularly the US, would rush to defend Taiwan against a Chinese invasion because they do not want Beijing to seize the nation’s vital and unique chip industry. However,

Life as we know it will probably not come to an end in Japan this weekend, but what if it does? That is the question consuming a disaster-prone country ahead of a widely spread prediction of disaster that one comic book suggests would occur tomorrow. The Future I Saw, a manga by Ryo Tatsuki about her purported ability to see the future in dreams, was first published in 1999. It would have faded into obscurity, but for the mention of a tsunami and the cover that read “Major disaster in March 2011.” Years later, when the most powerful earthquake ever