“Long Live the Virgin of El Rocio!” Not the first words that would occur to me if I were the recipient of a 25cm abdominal goring that reached my spine — one of the many reasons I am unlikely to ever have a successful career as a matador.

The last words uttered by Francisco Rivera before receiving medical treatment in August for a potentially fatal injury not only revealed that bullfighting remains inextricably linked with religious iconography, they also illustrated that the ability to face death in both theatrical and stoical terms is crucial to its allure and romance.

In technical terms Rivera has never been a first-class torero, but this is not a necessary or sufficient condition for success. At the age of 10, the grandson of the late torero Antonio Ordonez — idolized by Ernest Hemingway in The Dangerous Summer — lost his father to a bull in 1984. Rivera senior, popularly known as Paquirri, was confirmed a martyr and a saint as video footage circulated of a brave bullfighter bleeding to death and, at the same time, comforting a visibly panicked and unprepared surgeon.

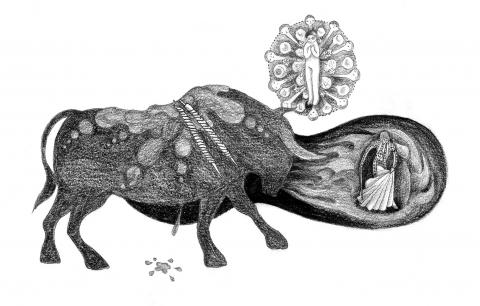

Illustration: Mountain People

Although vastly improved medical facilities have reduced fatalities, this year has been an unusually bloody year in human terms: As well as 13 fatalities in encierros (running with the bulls), several matadors endured life and career-threatening injuries in the ring.

For the first time in the modern age, the survival of what was once referred to as Spain’s national fiesta is also in jeopardy. Animal rights activists have found an audience among a significant proportion of the population who increasingly view bullfighting as a financial drain at a time of economic crisis and a symbol of the nation’s ills: Cruel, parasitical and out of touch with reality.

A profession with deep-seated internal divisions finds itself ill-equipped to defend itself against a concerted opposition and a rapid change in public mood. Funding cuts have put the future of training schools under threat. Controversial new plans by the Spanish Ministry of Education — run by the right-wing Popular Party — to safeguard their financial viability, by incorporating bullfighting into vocational training courses are meeting fierce opposition.

Former Spanish minister of culture Angeles Gonzalez-Sinde, of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, told me that young people who came of age in the early 1980s, in the aftermath of Franco’s death, often enjoyed going to watch the bulls, and that there was a strong admiration and affiliation with certain leading toreros who mixed with leading lights of La Movida, the drug-fueled youth movement that put film director Pedro Almodovar and his adopted city of Madrid on the international map. She believes this connection has been lost and that teenagers now see bullfighting as something alien to their increasingly globalized culture.

When I was at the Sonorama indie music festival this summer I had to go alone to a bullfight as none of my extended group wanted to accompany me. By contrast, two weeks later I found myself at a private beach club in Sotogrande — generally frequented by aging politicians, property tycoons, bankers and a diverse cast of players from the world of polo — and found the room where bullfights are broadcast on Canal+ to be a popular hotspot.

Retired Spanish monarch Juan Carlos is a fierce advocate of the bulls — his son, Spanish King Felipe VI, has retained a diplomatic silence — but this is of limited use to proponents of bullfighting when his standing in public opinion is at an all-time low. Images of the emeritus king in San Sebastian to celebrate the return of the bulls after three years did little to dispel ingrained prejudices about aficionados as cigar-smoking reactionary figures from an older generation.

The overturning of a prior prohibition in the Basque coastal city was the result of a change in municipal rule. In fact, it is impossible to understand the debates surrounding bullfighting without taking into account the territorial and political reality of a nation-state comprising 17 autonomous regions. Having been prohibited for many years in the Canary Islands, the 2011 ban in Catalonia fed into independence debates, evidence for nationalists of their distinction from the centralist state. This approach sidelined the tradition of bullfighting in and around Barcelona, while the dismissal of a cultural activity as the manifestation of a conservative Spanish heartland fails to mention that it continues to be practiced in much of southern France.

The world’s leading bullfighter Jose Tomas made a conscious decision to stage his comeback to a sold-out crowd in the Catalan capital in 2007; his 2012 solo performance in Nimes with six bulls — the standard format is for three toreros to take on two bulls each — is considered the finest corrida of the modern age.

While the unpredictability of an event that depends as much on an animal as a human being is crucial to the frisson of live performance, the communion between a torero, bull and audience rarely achieves the degree of synchronicity to satisfy the purist’s definition of art. This is a serious obstacle for the casual attendee, especially when decent tickets generally cost upwards of 50 euros (US$55.25) each. Hence the appeal of flamboyant showman and celebrity toreros that prove particularly popular in provincial bullrings.

In terms of pure entertainment, Juan Jose Padilla, replete with his now trademark eyepatch — the result of a near-fatal goring in 2011 — and pirate paraphernalia is difficult to beat, at least until one becomes (over-) familiar with some of his trademark tricks. I watched Morante de la Puebla, many aficionados’ matador of choice, booed for an under-par performance with a bull in Antequera last summer. The audience was more indulgent of a chaotic display by El Pana, a septuagenarian Mexican who smokes a cigar before taking his sword. The maverick, undeterred by the fact it took him six inelegant and cruel attempts to kill his second bull, lapped the ring at an ever-increasing speed, whipping the crowd into a frenzy as if he had just delivered a masterful piece de resistance.

The sanctity of the ritual has also been disrupted repeatedly this year by protesters jumping over the barrier.

Peter Janssen has been particularly active in this regard. In August the Dutch national jumped into a ring alongside a fellow protester in Marbella during an appearance by Morante, who subsequently refused to kill the second bull in protest against the police chastising his team for manhandling the intruders. The bullfighter has also taken legal action against activists for calling him a murderer.

The pro-bullfighting lobby often accuses their critics of anthropomorphism — the attribution of human qualities to animals — although they are hardly immune from this tendency. Fighting bulls always have names and commentators on Canal+ have been known to talk of how an under-performing animal is “lucky” to have a skilled torero able to bring out their best qualities.

Popular chants and slogans on demonstrations include “bullfights, the animal Guantanamo,” and “bullfighting, shame of the nation,” as well as “torture is not culture.”

The bigger and more troubling question is: does bullfighting’s cultural status justify its continued existence?

Artists Federico Garcia Lorca and Pablo Picasso were great aficionados, and individuals who would normally be considered civilized continue to take great pleasure in the act of watching a man face a potentially deadly animal.

Reared on processed meat, Anglo-American audiences increasingly have little direct contact with the harsh realities of nature and often lack a sensibility or vocabulary with which to discuss death.

However, perhaps the strongest argument against bullfighting is that aestheticization can distract from the reality of what is taking place. The moral challenge is to resist simplistic rejection without lapsing into a pastiche of Hemingway.

Duncan Wheeler is an associate professor in Spanish studies at the University of Leeds, and a visiting fellow of St Catherine’s College, Oxford.

As former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) concludes his fourth visit to China since leaving office, Taiwan finds itself once again trapped in a familiar cycle of political theater. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has criticized Ma’s participation in the Straits Forum as “dancing with Beijing,” while the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) defends it as an act of constitutional diplomacy. Both sides miss a crucial point: The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world. The disagreement reduces Taiwan’s

Former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) is visiting China, where he is addressed in a few ways, but never as a former president. On Sunday, he attended the Straits Forum in Xiamen, not as a former president of Taiwan, but as a former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chairman. There, he met with Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Chairman Wang Huning (王滬寧). Presumably, Wang at least would have been aware that Ma had once been president, and yet he did not mention that fact, referring to him only as “Mr Ma Ying-jeou.” Perhaps the apparent oversight was not intended to convey a lack of

A foreign colleague of mine asked me recently, “What is a safe distance from potential People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force’s (PLARF) Taiwan targets?” This article will answer this question and help people living in Taiwan have a deeper understanding of the threat. Why is it important to understand PLA/PLARF targeting strategy? According to RAND analysis, the PLA’s “systems destruction warfare” focuses on crippling an adversary’s operational system by targeting its networks, especially leadership, command and control (C2) nodes, sensors, and information hubs. Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, noted in his 15 May 2025 Sedona Forum keynote speech that, as

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) last week announced that the KMT was launching “Operation Patriot” in response to an unprecedented massive campaign to recall 31 KMT legislators. However, his action has also raised questions and doubts: Are these so-called “patriots” pledging allegiance to the country or to the party? While all KMT-proposed campaigns to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers have failed, and a growing number of local KMT chapter personnel have been indicted for allegedly forging petition signatures, media reports said that at least 26 recall motions against KMT legislators have passed the second signature threshold