Cambridge University neuropsychiatrist Valerie Voon has recently shown that men who describe themselves as addicted to porn (and who lost relationships because of it) develop changes in the same brain area — the reward center — that changes in drug addicts. The study, not yet published, is featured this week in a program on British TV — Porn and the Teenage Brain. Neuroskeptics may argue that pictures of the brain lighting up in addicts tell us nothing new — we already know they are addicted. However, they do help: knowing the reward center is changed explains some porn paradoxes.

In the mid-1990s I, and other psychiatrists, began to notice the following. An adult male, in a happy relationship, being seen for some non-romantic issue, might describe getting curious about porn on the burgeoning Internet. Most sites bored him, but he soon noticed several that fascinated him to the point he was craving them. The more he used the porn, the more he wanted to.

Yet, though he craved it, he did not like it (porn paradox 1). The cravings were so intense, he might feel them while thinking about his computer (paradox 2). The patient would also report that, far from getting more turned on by the idea of sex with his partner, he was less attracted to her (paradox 3). Through porn he acquired new sexual tastes.

We often talk about addicts as though they simply have “quantitative problems.” They “use too much” and should “cut back.” However, porn addictions also have a qualitative component: they change sexual taste. Here’s how.

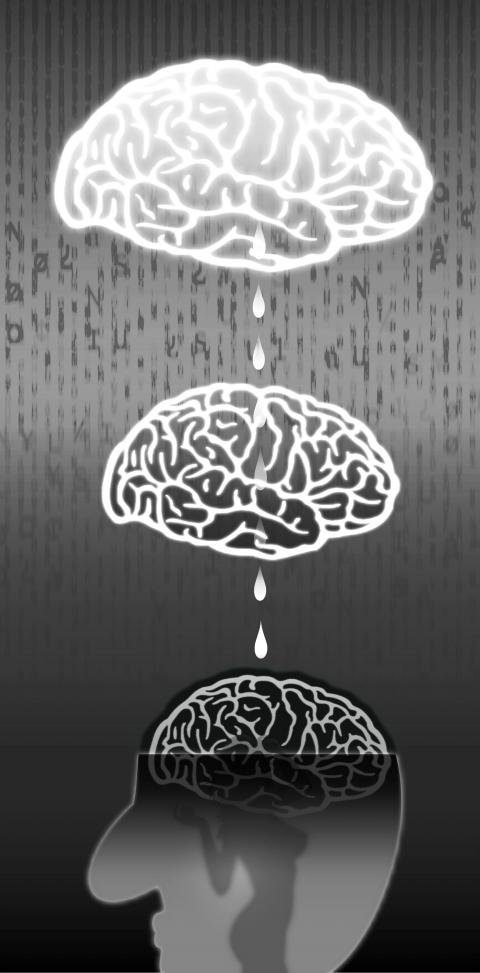

Until recently, scientists believed our brains were fixed, their circuits formed and finalized in childhood, or “hardwired.” Now we know the brain is “neuroplastic,” and not only can it change, but that it works by changing its structure in response to repeated mental experience.

One key driver of plastic change is the reward center, which normally fires as we accomplish a goal. A brain chemical, dopamine, is released, giving us the thrill that goes with accomplishment. It also consolidates the connections between neurons in the brain that helped us accomplish that goal. As well, dopamine is secreted at moments of sexual excitement and novelty. Porn scenes, filled with novel sexual “partners,” fire the reward center. The images get reinforced, altering the user’s sexual tastes.

Many abused substances directly trigger dopamine secretion — without us having to work to accomplish a goal. This can damage the dopamine reward system. In porn, we get “sex” without the work of courtship. Now, scans show that porn can alter the reward center too.

Once the reward center is altered, a person will compulsively seek out the activity or place that triggered the dopamine discharge. (Like addicts who get excited passing the alley where they first tried cocaine, the patients got excited thinking about their computers.) They crave despite negative consequences. (This is why those patients could crave porn without liking it.) Worse, a damaged dopamine system makes one more “tolerant” to the activity and needing more stimulation, to get the rush and quiet the craving. “Tolerance” drives a search for ramped-up stimulation, and this can drive the change in tastes towards the extreme.

The most obvious change in porn is how sex is so laced with aggression and sadomasochism. As tolerance to sexual excitement develops, it no longer satisfies; only by releasing a second drive, the aggressive drive, can the addict be excited. And so — for people psychologically predisposed — there are scenes of angry sex, men ejaculating insultingly on women’s faces, angry anal penetration, etc. Porn sites are also filled with the complexes Freud described: “Milf” (“mothers I’d like to fuck”) sites show us the Oedipus complex is alive; spanking sites sexualize a childhood trauma and many other oral and anal fixations. Porn does not “cause” these complexes, but it can strengthen them, by wiring them into the reward system. The porn triggers a “neo-sexuality” — an interplay between the pornographer’s fantasies, and the viewer’s.

Teenagers’ brains are especially plastic. Now, 24/7 access to Internet porn is laying the foundation of their sexual tastes. In Beeban Kidron’s InRealLife, a film about the effects of the Internet on teenagers, a 15-year-old boy of extraordinary honesty and courage articulates what is going on in the lives of millions of teen boys. He shows her the porn images that excite him and his friends, and describes how they have molded their “real life” sexual activity. He says:

“You’d try out a girl and get a perfect image of what you’ve watched on the Internet... you’d want her to be exactly like the one you saw on the Internet ... I’m highly thankful to whoever made these Web sites, and that they’re free, but in other senses it’s ruined the whole sense of love. It hurts me because I find now it’s so hard for me to actually find a connection to a girl,” he says.

The sexual tastes and the romantic longings of these boys have become dissociated from each other. Meanwhile, the girls have “downloaded” on to them the expectation that they play roles written by pornographers. Once, porn was used by teens to explore, prepare and relieve sexual tension, in anticipation of a real sexual relationship. Today, it supplants it.

In her book, Bunny Tales: Behind Closed Doors at the Playboy Mansion, Izabella St James, one of Playboy magazine publisher Hugh Hefner’s former “official girlfriends,” described sex with Hef. Hef, in his late 70s, would have sex twice a week, sometimes with four or more of his girlfriends at once. He had novelty, variety, multiplicity and women willing to do what he pleased. At the end of the happy orgy, wrote St James, came “the grand finale: he masturbated while watching porn.”

Here, the man who could actually live out the ultimate porn fantasy, with real porn stars, instead turned from their real flesh and touch, to the image on the screen. Now, I ask you: “What is wrong with this picture?”

Norman Doidge, a physician, is author of The Brain That Changes Itself.

As former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) concludes his fourth visit to China since leaving office, Taiwan finds itself once again trapped in a familiar cycle of political theater. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has criticized Ma’s participation in the Straits Forum as “dancing with Beijing,” while the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) defends it as an act of constitutional diplomacy. Both sides miss a crucial point: The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world. The disagreement reduces Taiwan’s

A foreign colleague of mine asked me recently, “What is a safe distance from potential People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force’s (PLARF) Taiwan targets?” This article will answer this question and help people living in Taiwan have a deeper understanding of the threat. Why is it important to understand PLA/PLARF targeting strategy? According to RAND analysis, the PLA’s “systems destruction warfare” focuses on crippling an adversary’s operational system by targeting its networks, especially leadership, command and control (C2) nodes, sensors, and information hubs. Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, noted in his 15 May 2025 Sedona Forum keynote speech that, as

Former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) is visiting China, where he is addressed in a few ways, but never as a former president. On Sunday, he attended the Straits Forum in Xiamen, not as a former president of Taiwan, but as a former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chairman. There, he met with Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Chairman Wang Huning (王滬寧). Presumably, Wang at least would have been aware that Ma had once been president, and yet he did not mention that fact, referring to him only as “Mr Ma Ying-jeou.” Perhaps the apparent oversight was not intended to convey a lack of

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) last week announced that the KMT was launching “Operation Patriot” in response to an unprecedented massive campaign to recall 31 KMT legislators. However, his action has also raised questions and doubts: Are these so-called “patriots” pledging allegiance to the country or to the party? While all KMT-proposed campaigns to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers have failed, and a growing number of local KMT chapter personnel have been indicted for allegedly forging petition signatures, media reports said that at least 26 recall motions against KMT legislators have passed the second signature threshold