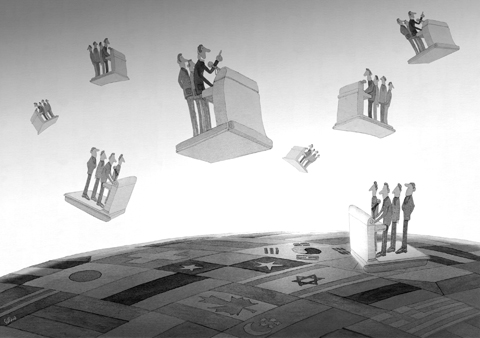

International climate change negotiations are to be renewed this year. To be successful, they must heed the lessons of the Copenhagen summit in December.

The first lesson is that climate change is a matter not only of science, but also of geopolitics. The expectation at Copenhagen that scientific research would trump geopolitics was misguided. Without an improved geopolitical strategy, there can be no effective fight against climate change.

The second lesson from Copenhagen is that to get a binding international agreement, there first must be a deal between the US and China. These two countries are very dissimilar in many respects, but not in their carbon profiles — each accounts for between 22 percent and 24 percent of all human-generated greenhouse gases in the world. If a deal can be reached between the world’s two greatest polluting nations, which together are responsible for more than 46 percent of all greenhouse-gas emissions, an international accord on climate change would be easier to reach.

In Copenhagen, China cleverly deflected pressure by hiding behind small, poor countries and forging a negotiating alliance, known as the BASIC bloc, with three other major developing countries — India, Brazil and South Africa.

The BASIC bloc, however, is founded on political opportunism and is therefore unlikely to hold together for long. The carbon profiles of Brazil, India, South Africa and China are wildly incongruent. For example, China’s per-capita carbon emissions are more than four times higher than India’s.

China rejects India’s argument that per-capita emission levels and historic contributions of greenhouse gases should form the objective criteria for carbon mitigation. China, as the factory to the world, wants a formula that marks down carbon intensity linked to export industries. As soon as the struggle to define criteria for mitigation action commences in future negotiations, this alliance will quickly unravel.

A third lesson from Copenhagen is the need for a more realistic agenda. Too much focus has been put on carbon cuts for nearly two decades, almost to the exclusion of other elements. It is now time to disaggregate the climate change agenda into smaller, more manageable parts. After all, a lot can be done without a binding agreement that sets national targets on carbon cuts.

Consider energy efficiency, which can help bring a quarter of all gains in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Energy inefficiency is a problem not only in the Third World, but also in the developed world. The US, for instance, belches out twice as much carbon dioxide per capita as Japan, although the two countries have fairly similar per-capita incomes.

Furthermore, given that deforestation accounts for as much as 20 percent of the emission problem, carbon storage is as important as carbon cuts. Each hectare of rainforest, for example, stores 500 tonnes of carbon dioxide. Forest conservation and management therefore are crucial to tackling climate change. In fact, to help lessen the impact of climate change, states need to strategically invest in ecological restoration — growing and preserving rainforests, building wetlands and shielding species critical to our ecosystems.

The international community must also focus on stemming man-made environmental change. Environmental change is distinct from climate change, although there is a tendency on the part of some enthusiasts to blur the distinction and turn climate change into a blame-all phenomenon.

Man-made environmental change is caused by reckless land use, overgrazing, depletion and contamination of surface freshwater resources, overuse of groundwater, degradation of coastal ecosystems, inefficient or environmentally unsustainable irrigation practices, waste mismanagement and the destruction of natural habitats. Such environmental change has no link to climate change, yet, ultimately, it will contribute to climate variation and thus must be stopped.

Climate change and environmental change, given their implications for resource security, and social and economic stability, are clearly threat multipliers. While continuing to search for a binding international agreement, the international community should also explore innovative approaches, such as global public-private partnership initiatives.

As the international community’s experience since the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change shows, it is easier to set global goals than to implement them. The non-binding political commitments reached in principle at Copenhagen already have run into controversy, as well as varying interpretations, dimming the future of the so-called “Copenhagen Accord,” an ad hoc, face-saving agreement stitched together at the 11th hour to cover up the summit’s failure. Only 55 of the 194 countries submitted their national action plans by the accord’s Jan. 31 deadline.

The climate change agenda has become so politically driven that important actors have tagged onto it all sorts of competing interests, economic and otherwise. That should not have been allowed to happen, but it has, and there can be no way forward unless and until we confront that fact.

Brahma Chellaney is professor of strategic studies at the Center for Policy Research in New Delhi.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

A failure by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to respond to Israel’s brilliant 12-day (June 12-23) bombing and special operations war against Iran, topped by US President Donald Trump’s ordering the June 21 bombing of Iranian deep underground nuclear weapons fuel processing sites, has been noted by some as demonstrating a profound lack of resolve, even “impotence,” by China. However, this would be a dangerous underestimation of CCP ambitions and its broader and more profound military response to the Trump Administration — a challenge that includes an acceleration of its strategies to assist nuclear proxy states, and developing a wide array

Eating at a breakfast shop the other day, I turned to an old man sitting at the table next to mine. “Hey, did you hear that the Legislative Yuan passed a bill to give everyone NT$10,000 [US$340]?” I said, pointing to a newspaper headline. The old man cursed, then said: “Yeah, the Chinese Nationalist Party [KMT] canceled the NT$100 billion subsidy for Taiwan Power Co and announced they would give everyone NT$10,000 instead. “Nice. Now they are saying that if electricity prices go up, we can just use that cash to pay for it,” he said. “I have no time for drivel like

Twenty-four Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers are facing recall votes on Saturday, prompting nearly all KMT officials and lawmakers to rally their supporters over the past weekend, urging them to vote “no” in a bid to retain their seats and preserve the KMT’s majority in the Legislative Yuan. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which had largely kept its distance from the civic recall campaigns, earlier this month instructed its officials and staff to support the recall groups in a final push to protect the nation. The justification for the recalls has increasingly been framed as a “resistance” movement against China and

Jaw Shaw-kong (趙少康), former chairman of Broadcasting Corp of China and leader of the “blue fighters,” recently announced that he had canned his trip to east Africa, and he would stay in Taiwan for the recall vote on Saturday. He added that he hoped “his friends in the blue camp would follow his lead.” His statement is quite interesting for a few reasons. Jaw had been criticized following media reports that he would be traveling in east Africa during the recall vote. While he decided to stay in Taiwan after drawing a lot of flak, his hesitation says it all: If