I have been following the financial markets for more than 30 years. Crises have come and gone, but the one unfolding since August and which intensified last week is the most serious. It is not just that its impact is cascading around the world because of the new interconnectedness of global finance, it is that the authorities, particularly in Britain and the US, have lost control and do not have the means to regain it as quickly as we might hope. With an oil price approaching US$100 a barrel, we are in an uncharted and dangerous place.

After more than 15 years of extraordinarily benevolent economic conditions worldwide -- cheap oil, cheap money, growing trade, the Asia boom, rising house prices -- things are unraveling at a bewildering speed. The system might be able to handle one shock; it is undoubtedly too fragile to handle so many simultaneously.

The epicenter is the hegemonic London and New York financial system. No longer are these discrete financial markets; financial deregulation and the global ambitions of US and European banks have made them intertwined. They are one system that operates around the same principles, copying each other's methods, making the same mistakes and exposing themselves to each other's risks.

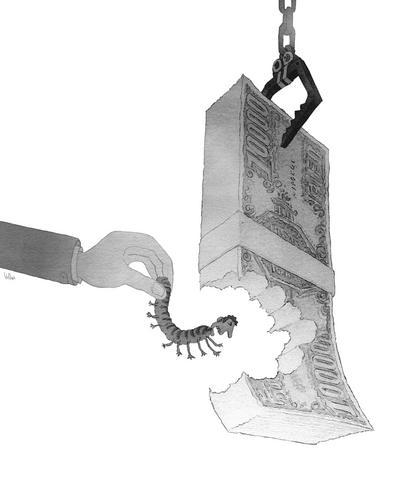

Thus the collapse of the US housing market, the explosive growth of US home repossessions and the discovery that structured investment vehicles (SIVs), the toxic newfangled financial instruments that own as much as US$350 billion of valueless mortgages, are not US problems. They are ours too.

The recent departure of the chief executive officers of two of the biggest investment banks -- UBS and Merrill Lynch -- after unexpected losses and loan write-offs running into many billions of dollars is not just a US problem, it's ours. It is also our problem that Credit Suisse last week announced more billions of write-offs, and Citigroup was rumored to be following suit with even bigger losses. When banks take hits as big as this, it hurts their capacity to lend, because prudence demands they have up to US$8 of their own capital to support every US$100 that they lend. If they don't, they have to lend less -- and that is called a credit crunch.

This crunch is already upon us -- hence the massive selling of bank shares at the end of last week and the extraordinary news that the taxpayer, one way or another, now has supplied ?40 billion (US$83.2 billion) to the stricken British mortgage lender Northern Rock, a sum that could climb to ?50 billion by Christmas. Stunningly, that represents 5 percent of GDP.

The bank got into trouble because it thought, under the chairmanship of free-market fundamentalist Viscount Ridley, that it could escape trivial matters like having savers' deposits to finance its adventurous lending. Instead, it could copy the Americans and sell SIVs to banks in London -- most of them the same banks that bought from New York -- and it could steal a march on its competitors.

But in the London-New York financial system, when things went wrong in the US they immediately went wrong for Northern Rock in Britain. The banks announcing those epic write-offs no longer wanted to buy Northern Rock's loans -- and neither did anybody else. The Bank of England and Treasury hoped to get by with masterly inactivity, but instead, as we know, there was a run on the bank. The government had to step in by guaranteeing ?20 billion of small savers' deposits -- but also, we now learn, by supplying ?30 billion of finance that the financial system will no longer supply itself.

This is testimony to the degree of fear that characterizes today's credit crunch -- and it bodes ill. What is worse, the Ridleyite maxims that got Northern Rock into trouble have also disabled the rescue, protracting rather than limiting the crisis.

What should have happened, of course, is that when the Bank of England found that it could not find a secret buyer for Northern Rock in the summer, it should have done what it did in the 1974 secondary banking crisis. It should have taken Northern Rock into the Bank of England's ownership.

Individual depositors and the City of London institutions alike would have been quickly reassured, and when the crisis passed the bank could have been sold back into the private sector.

But this year, the Ridley view of how to run a bank is also the authorities' view of how to respond to a crisis. There is a prohibition on even short-term public ownership. In a free-market fundamentalist world, this, like regulation, is regarded as wrong. Instead, the most expensive and riskier route has been taken so that Northern Rock remains part of the problem rather than the solution.

For when a central bank supplies rescue finance on this epic scale, it has wider implications. In effect it is printing money to bail out Northern Rock; good for the financial system, but bad for the rest of us because it will make it harder for the Bank of England to cut interest rates.

Already the British property market is in trouble. Given the absurd prices it is all too possible that we could follow the US market, with huge bad debts and mortgage repossessions.

The way Northern Rock has been rescued will make it hard for the Bank of England to cut interest rates and revive the property market, while remaining wedded to its inflation target. And if there are more Northern Rocks rescued in the same way, the dilemma will get worse.

Last week David Cameron, leader of the opposition Conservatives, proudly pronounced that his party was winning the battle of ideas in British politics. He could not be more wrong.

The credit crunch is testimony to the exhaustion of a conservative free-market world-view. To get through this crisis, the US and British governments are going to have to think what hitherto has been unthinkable.

Already the Americans are cutting interest rates careless of the inflationary consequences. Britain may have to follow suit. Both governments will have to do more. Banks may have to be taken into public ownership.

For 30 years we have been suckered into thinking that public authority has no business intervening in the wealth-generating, free-market financial system. This is the year when reality resurfaced with a vengeance.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s