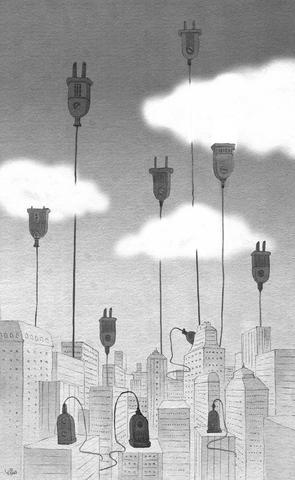

Across the world, doomsayers are smiling. The mounting signs of climate change have forced onto center stage the challenges of reducing carbon emissions and quickly adapting human activities to thrive in higher temperatures and more unpredictable weather.

Alas, the bad news about climate change is good news for business.

A curious feature of capitalism is that threats, or more precisely, the human response to them, are economically and technologically stimulating.

Or, to put it another way, "Necessity is the mother of invention."

There will always be doomsayers, and fantasies about the end of human society are a staple of Hollywood and science fiction. But these days, a lot of smart people are seriously contemplating the looming destruction of human society, whether through a cascade of natural disasters, nuclear wars, uncontrolled terrorism, novel pandemics or, of course, climate change. Because I attended the Woody Allen school of futurism and generally find humanity poised between the horrible and the terrible, I always remember the childhood story of the boy who cried wolf.

Cry too often about ill-formed threats and you lose all credibility. But there are good reasons to believe that crying wolf is exactly what the brightest innovators ought to be doing, and not only in response to the challenge of climate change. As a general matter, high anxiety will lead to more intense pursuit of innovation.

In the history of economics, the ultimate wolf-crier was Joseph Schumpeter. An Austrian economist who taught at Harvard, Schumpeter in 1942 coined the term "creative destruction" to describe what he viewed as the engine of capitalism: how new products and processes constantly overtake existing ones. In his classic work, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, he described how unexpected innovations destroyed markets and gave rise to new fortunes.

The historian Thomas McCraw writes in his new biography of Schumpeter, Prophet of Innovation: "Schumpeter's signature legacy is his insight that innovation in the form of creative destruction is the driving force not only of capitalism but of material progress in general. Almost all businesses, no matter how strong they seem to be at a given moment, ultimately fail and almost always because they failed to innovate."

Schumpeter's concept of creative destruction is justly celebrated. The economics writer David Warsh calls it the most memorable economic phrase since Adam Smith's "invisible hand." Peter Drucker, the late business guru, went so far as to declare Schumpeter the most influential economist of the last century.

Clearly, any quick survey of technological change validates Schumpeter's essential insight. The DVD destroyed the videotape (and the businesses around it). The computer obliterated the typewriter. The automobile turned the horse and buggy into an anachronism. Today, the Web is destroying many businesses even as it gives rise to others. Though the compact disc still lives, downloadable music is threatening to make the record album history.

"Schumpeter's central idea is just as important now as ever," says Louis Galambos, a business historian at Johns Hopkins University. "The heart of capitalism and its claim as an efficient economic system over the long term is the role that innovation plays."

Schumpeter brilliantly realized that innovation -- so often extolled as the purest expression of the human spirit -- has a dark, violent, even nasty side. Every innovator, in short, makes a declaration of war. And every successful innovation is a destroyer. To be sure, in these wars only technologies die, not the people who stand behind them. Yet people suffer nevertheless. Richard Fisher, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, said in a speech last month that he knew firsthand of "the painful adjustments that economic advancement inflicts upon displaced workers."

"I grew up in a household where my father suffered more than his fair share of the destructive side of that process," Fisher said. "It was difficult for him to grasp the allure of the creative side of the equation, and I am more familiar with the anguish that comes when a breadwinner loses his job."

Fisher dwelled on the anguish felt by the losers in technological battles to point up the need for government and society to treat the losers with compassion. Yet liberal impulses to both embrace the new and assist those swept aside by technological change ignore an enigma: that destruction itself is often liberating, unleashing waves of innovation.

Even all-out war can lay the seeds of creative destruction. The leveling of Germany and Japan at the end of World War II forced the rebuilding of factories in those countries with the latest technologies, catapulting them into the first ranks of industrial powers. In addition to wiping out old physical structures, wars can obliterate old intellectual and organizational structures that restrain innovators.

"Violence breaks old relationships and upends people in power," says Joel Migdal, a professor of international studies at the University of Washington. "Once these structures and people are swept away, all sorts of things can happen."

Economic growth isn't guaranteed after an all-out war, naturally. Liberia and Sierra Leone are proof of that. But the hope that creation can follow destruction is motivating the leaders of Rwanda, where the 1994 genocide wiped out the country's social networks. Rwandans are supporting a range of initiatives, like new universities, a movie-making center and investments in technology from companies like Google, that they hope will promote an innovative economy based on creativity.

War, of course, is only the most dramatic form of destruction. In the case of climate change, humanity faces a hydra-headed threat, where the risks remain hard to identify with precision and the costs, at least for now, are borne chiefly in the poorest parts of the tropics.

Until recently, environmental wolf-criers emphasized the need to reduce emissions drastically, thus ensuring stability for human communities at some date in the future. Now experts are increasingly convinced that new technologies are widely and urgently needed, including drought-resistant crops, more efficient uses of water, new sources of energy and new building materials.

These new technologies, publicized by wolf-criers and driven by the impulse for self-preservation, will ultimately supplant existing products and processes -- and remind us anew that the pursuit of innovation is the moral equivalent of war.

G. Pascal Zachary teaches journalism at Stanford University

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s