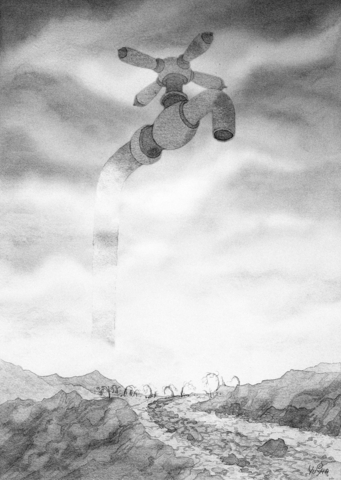

Some economic booms grind to a halt, others run out of steam, but in China the biggest risk is that growth will dry up. Water, the country's scarcest resource, is running out. Pollution, waste and over-exploitation have combined with the expansion of mega-cities to foul up wells and suck rivers dry.

Signs of a crisis are apparent everywhere. In the arid north, four-fifths of the wetlands along the region's biggest river system have dried up. In the west, desert sands are encroaching on many cities. In the south, the worst drought in 50 years has ruined crops and prompted water shortages even along the banks of the Yangtze River, the nation's biggest waterway.

Domestic newspapers are increasingly filled with grim statistics and reports of the latest pollution spill. In June, the state environment protection agency estimated that 90 percent of urban water supplies were contaminated with organic or industrial waste. According to the water resources ministry, 400 of the country's 600 cities are short of water.

Water has always been China's Achilles heel. The world's most populous country has per capita water resources of 2,200m3 -- less than a quarter of the world average. The shortfall between supply and demand is estimated at 6 billion cubic meters. The gap is likely to widen as the population grows from 1.3 billion people to an estimated 1.6 billion by 2030.

Worsening the problem is the stark regional variation between the dry north and the wet south. Beijing -- one of 110 cities deemed to suffer from "extreme shortages" -- has been forced to import supplies from a widening circle of sources.

In short, China's development model is unsustainable. For the past 30 years the government has emphasized the quantity rather than the quality of growth. Spectacular expansion figures of almost 10 percent a year mask dire inefficiency and environmental damage. For most of the past 30 years, financial resources have been invested in new factories rather than treatment plants, water recycling facilities or replacements for leaky pipes.

Only 52 percent of the country's 2 billion cubic meters of sewage is treated before it goes into rivers and lakes. This has expensive health implications. Each year, filthy water is a big factor in the 800 million cases of diarrhea, 650,000 cases of dysentery and 500 million cases of intestinal worms.

Industrial pollution creates political as well as physical concerns. Suspicions are rife that factory owners collaborate with government officials to cover up toxic spills in the interests of social stability and economic growth. But China's water crisis is not only the responsibility of officials and developers. Scientists blame global warming for the shrinking of glaciers and the disappearance of thousands of lakes in the Himalayas and other mountain regions in the west of China.

Climate change is also thought to have contributed to the worst drought in 50 years in Chongqing and Sichuan. No rain has fallen for 10 weeks and two-thirds of the rivers have dried up. Worse may be yet to come.

The head of the China Meteorological Administration has told China Energy Weekly that global warming will lead to shortages of 20 billion cubic meters of water in western China by 2030. There are signs that the government is taking these warnings more seriously.

President Hu Jintao (

Yet the prevailing ethos is that the problems of growth and science can be solved by more growth and more science. Cloud seeding is being used to induce precipitation artificially. Despite the increasingly evident environmental impact of giant hydroelectric plants such as the Three Gorges Dam, the nation's thirst for energy has pushed policy makers to announce plans for dozens of dams along the tributaries of the Yangtze, the Yellow and the Nu rivers.

The biggest hydro-engineering plan of all has just started. The US$63 billion north-south water diversion plan involves the construction of three giant canals from the Yangtze up to the arid north and west. The work is expected to take 50 years. Once completed, it will channel 44 billion cubic meters of water across the Chinese landmass.

Environmentalists argue that China needs a fundamental change of philosophy. Although Hu's administration has promoted sustainable development for three years, local governments do not appear to be listening. Why should they? With no elections and no free media, cadres are more worried about their superiors than the people they are supposed to serve.

The government admits that the problems of water shortages and pollution are getting worse. Clean-up goals set last year already look unattainable. In the first six months of this year the government's key index of water pollution -- chemical oxygen demand -- rose 3.7 percent and discharges of sulphur dioxide increased 4.2 percent.

If there is a positive side, it is that the water crisis could help to open up a closed society and make it more environmentally conscious. In recent years, Beijing has shown a willingness to listen to green non-governmental organizations, which would have been unthinkable in the past.

Ma Jun (馬軍), author of China's Water Crisis, says the next step is to foster greater public accountability so that people can act as a brake on unsustainable development of their communities.

"China has the technology and the money to solve this problem. But environmental departments usually find it difficult to enforce the law because local governments protect business first. What is needed is the involvement of the public," Ma said.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.