The first thing Koji Saito does when I walk through the front door of his home in Sakaemura is laugh -- a raucous guffaw that leaves his eyes glistening with moisture. Minutes later, he is at it again as we take our places on the tatami mat floor of his living room while his wife and daughter-in-law pour cups of steaming green tea.

Saito has plenty to be happy about. At 88, he is the picture of health, the only obvious concession to age a hearing aid in his left ear. He is still fit enough to ride his motorcycle, at speeds that horrify his family, up the hill every morning after breakfast to perform the backbreaking task of pulling weeds from the deep, dark sludge of his rice paddies.

Should he ever feel the need for companionship, unlikely though that is for a married man who lives with three other generations of his family, he needn't venture far. In Sakaemura, a village of 2,500 people hidden among the mountains of Nagano prefecture, north-west of Tokyo, almost half of the inhabitants (1,061 people), are over 65.

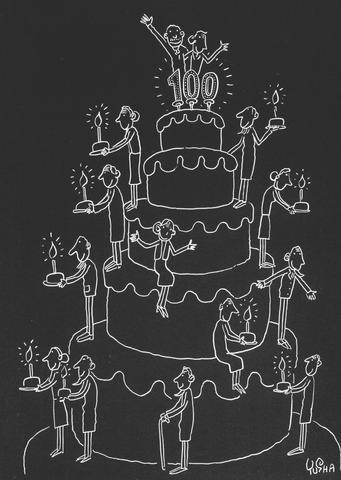

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

The men of Nagano prefecture live longer than those elsewhere in Japan. In 2000, according to the health ministry, they could expect to live until they were almost 79, while the women, with an average life expectancy of 85, ranked third nationally.

Similarly impressive statistics have been recorded across Japan, where life expectancy has increased dramatically during the past 80 years. In 1935, life expectancy was about 45. By 1950, that figure had risen to 60. Today it stands at 85 for women and 78 for men.

Japanese women live, on average, over five years longer than those in the US. Japanese men typically have more than four years on those in the US. The number of centenarians in Japan has doubled in the past five years and now stands at just over 20,000.

So what is behind the phenomenon of Japanese life expectancy? Most theories have centered on the low-fat diet of fish, rice and soy products such as tofu. But diet is just one of the factors that combine to make for a longer, healthier life. While few scientific studies point to definite explanations for Japan's long-living population, there is no shortage of possibilities. Universal health insurance, achieved in the early 1960s, undoubtedly has an impact, as does the generous state pension scheme. In Japan, poverty in old age is rare.

Education also plays a role.

"There is no illiteracy, even among people aged 70 and over," says Takao Suzuki, vice-director of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology. "They are very sensitive about information on health problems, so I would say education is one of the important factors."

Suzuki says the benefits of the traditional Japanese diet have been made possible by economic development. Before the Second World War, the average intake of animal protein was less than 7g a day, but has risen to a near-ideal 40g, along with a similar level of vegetable protein. While cholesterol intake is rising, it has not reached the levels seen in the west, where there are unprecedented levels of obesity.

The nanny state, guaranteed to cause hyperventilation on the British right, is alive and well in Japan. The elderly are an important part of "Healthy Japan 21," a collection of 70 public health targets the health ministry wants to achieve by 2010. They include reducing salt intake (from the current 13.5g to 10g a day) by persuading people to cut down on salty staples such as miso soup and pickled vegetables.

"That is not all," says Teiji Takei, deputy director in the ministry's office for lifestyle-related diseases. "Even the elderly should be encouraged to take regular exercise."

The ministry has devised walking targets for different age groups.

Local authorities encourage people of all ages to have regular health checkups. Officials in Nagano talk proudly of their network of health workers and volunteers who make regular house calls on elderly neighbors. Much is made, too, of the life-enhancing qualities of local food staples such as bamboo shoots and other root vegetables.

If contentment is the key, what the Japanese lose in terms of holidays and spacious homes, they gain in extended family ties and a sense of community, particularly in farming villages of the kind found all over Nagano.

"We know that social networking makes people healthier, happier and that means they live longer," says Kevin Kinsella, special assistant at the US census bureau's international programs centre in Washington.

Elderly Japanese appear just as gregarious as the urban young. According to government figures, a quarter of all over-65s socialize regularly with neighbors, with 20 percent preferring daily contact.

Kinsella suggests that lifetime employment, though under threat in post-bubble Japan, removes much of the stress experienced by workers in the more unpredictable job markets of Europe and North America and, as a result, produces a healthier retirement-age population. In 2002, some 4.8 million Japanese aged 65 or over were still part of the labor force, making up 7 percent of the total.

But even after the pieces of the longevity jigsaw have been put in place, the picture is still muddled. After all, the Japanese are not alone in reaping the dividends of economic development, such as greater variety of food, higher incomes, more leisure choices and advanced social security and health services. And though alcohol consumption is relatively low, the Japanese -- particularly men -- smoke far more than their G7 counterparts. Urban residents, meanwhile, with their long working hours, short holidays and cramped homes, are no strangers to stress, recognized as a contributor to potentially fatal illnesses.

The men and women of Okinawa, Japan's southernmost prefecture, top the national life expectancy table -- thanks, experts say, to the subtropical island's warm climate and unhurried pace of life. But environmental factors do not explain the extraordinarily long lives of residents of Nagano, where the winters are bitterly cold and daily routines are determined by the unforgiving demands of farming.

Theories abound, but science has yet to come up with a convincing answer.

"It is a mystery to everyone," says Kinsella. "There is no consensus on why they live so long, as there is no real empirical evidence to back up the various theories."

If the government reaches its health targets, the Japanese could add a year, possibly two, to their life expectancy over the next six years.

"I wouldn't be surprised if they manage an increase of a year, but two years would be a real achievement," says Kinsella. "There is no sign of slowing down in Japan."

There certainly isn't. By 2030, the over-65s will account for almost 30 percent of the projected population of 117 million.

Some gerontologists argue that reductions in mortality could see people in Japan living an average of 100 years in about six decades' time. But the country faces new health threats that could knock it off course. Top of the list is the emergence of lung cancer and diabetes. While stomach cancer, the most common cause of cancer deaths 20 years ago, has declined significantly thanks to improvements in diet, screening and treatment, lung cancer is now a leading cause of death.

In addition, the feted traditional Japanese diet that sustains Saito and his neighbors in Sakaemura is no longer to everyone's taste. "Younger people are eating far more processed and fast food than their predecessors, so we're trying to get them to look again at their eating habits," Takei says.

Warnings about the dangers of eating too much salt have seen intake fall after the war. As a result, strokes are no longer the No. 1 killer in Japan -- that dubious honor belongs to cancer, followed by heart disease.

According to Suzuki, a new system of more sophisticated health checks is needed to take into account the different risks facing men and women. The key to increasing longevity among men is still stroke prevention, while for women, it is arresting the decline in muscle and bone strength. "This is something we can focus on over the next 10 or 20 years," he says.

Saito says he has little idea why he remains so active. Though he is just one of many Japanese to see out his eighties in robust health, his life story offers several clues. To begin with, he nurtured the habits that have ensured a healthy retirement decades ago, when, as a 15-year-old school-leaver, he started his first job, helping his father take parcels on foot from the village to the collection point in Akiyama -- a daily round-trip of 24km.

He has never been a drinker or smoker, and eats three modest meals every day, seated at the table with the rest of his family. He eats lots of fruit and vegetables, and prefers rice to bread. His daughter-in-law adds to the list as she offers us his favorite "longevity food" -- a selection of mountain roots simmered in soy sauce.

He never loses his temper, she says, and gives himself a regular mental workout by reading the newspaper and writing frequently to his siblings. He goes to bed as soon as he finishes his dinner, and is up at 6am.

But there is another side to his life that has little to do with sensible lifestyle choices or government health policy.

"Look at what I have," Saito says as his great-granddaughter crawls into the room. "I'm living here among four generations of my family. We are all healthy and have lots of fun together. Whenever I see the children playing around the house, I think how nice it would be to be able to enjoy at least another year of this."

Dos and don'ts - how the Japanese live long and prosper

Drink in moderation and don't smoke. Go to bed early and get up early. Eat plenty of fish, fruit and vegetables. Avoid red meat, salty and processed food. Eat three meals a day, ideally at the same time each day. Eat tofu at least once a week. Drink green tea once a day. Eat less as you grow older. Take daily exercise, even if it is just walking to the shops rather than driving. Grow your own vegetables.

Prevention, or at least early detection, of disease, is better than cure. Take a health examination at least once a year. New screening technology has dramatically cut the death toll from stomach cancer in Japan.

Talk to your neighbors, however hard that may be. Japanese health experts believe that being active in the community and having regular face-to-face contact with friends and neighbors reduces stress.

Keep a lid on your temper. Laugh in the face of adversity.

Read and learn, even if failing eyesight means resorting to the use of a magnifying glass. Take advantage of the courses on offer for retired people.

Work beyond retirement age if possible, provided, of course, that you enjoy your job. Millions of Japanese do this, and apparently feel better for it.

Try to negotiate a semi-retirement buffer period before putting your feet up for good. Plan ahead and decide what you're going to do with all that free time.

Move back in with your children in old age, if they'll have you.

Immerse yourself in the youth of your grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

When US budget carrier Southwest Airlines last week announced a new partnership with China Airlines, Southwest’s social media were filled with comments from travelers excited by the new opportunity to visit China. Of course, China Airlines is not based in China, but in Taiwan, and the new partnership connects Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport with 30 cities across the US. At a time when China is increasing efforts on all fronts to falsely label Taiwan as “China” in all arenas, Taiwan does itself no favors by having its flagship carrier named China Airlines. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is eager to jump at

The muting of the line “I’m from Taiwan” (我台灣來欸), sung in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), during a performance at the closing ceremony of the World Masters Games in New Taipei City on May 31 has sparked a public outcry. The lyric from the well-known song All Eyes on Me (世界都看見) — originally written and performed by Taiwanese hip-hop group Nine One One (玖壹壹) — was muted twice, while the subtitles on the screen showed an alternate line, “we come here together” (阮作伙來欸), which was not sung. The song, performed at the ceremony by a cheerleading group, was the theme

Secretary of State Marco Rubio raised eyebrows recently when he declared the era of American unipolarity over. He described America’s unrivaled dominance of the international system as an anomaly that was created by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Now, he observed, the United States was returning to a more multipolar world where there are great powers in different parts of the planet. He pointed to China and Russia, as well as “rogue states like Iran and North Korea” as examples of countries the United States must contend with. This all begs the question:

In China, competition is fierce, and in many cases suppliers do not get paid on time. Rather than improving, the situation appears to be deteriorating. BYD Co, the world’s largest electric vehicle manufacturer by production volume, has gained notoriety for its harsh treatment of suppliers, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability. The case also highlights the decline of China’s business environment, and the growing risk of a cascading wave of corporate failures. BYD generally does not follow China’s Negotiable Instruments Law when settling payments with suppliers. Instead the company has created its own proprietary supply chain finance system called the “D-chain,” through which