Air fares are up. Petrol prices are up. The leaders of the 2000 fuel protest in the UK have been making minatory noises. None of this was in the script a year ago, when US President George W. Bush was boasting of final victory in Gulf War 2, so it is hardly surprising that Prime Minister Tony Blair is concerned about rising oil prices. With the £0.88 per liter (US$1.55) in prospect for British motorists, he's a worried man.

For the first time, there is evidence that the ripple effects from the mess in postwar Iraq are lapping up on the shores of the domestic economy. And for a prime minister counting down the days to a general election, that's not good news.

Understandably, the economic effects of the war have attracted scant interest over the past couple of weeks as Bush and Blair have floundered around in response to the revelations of torture by US and British troops in Iraq. The worsening political and security situation has, however, made both leaders more vulnerable to the most obvious consequence of instability in the Middle East -- a higher oil price. Over the past month, the price of a barrel of crude in New York has risen to just under US$40 a barrel, leading some economists to predict pump prices in the UK could rise by 10 percent over the coming weeks.

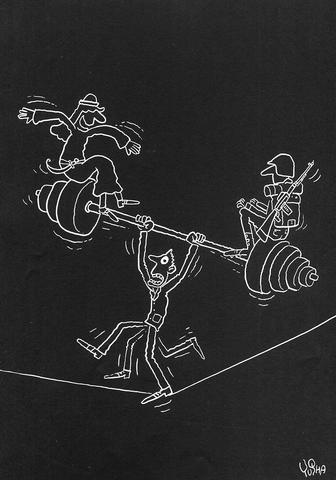

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

If you take the official statements from Washington and London at face value, Bush and Blair ought to consider this a price worth paying. They went to war because former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein was thoroughly wicked; the conflict had nothing -- absolutely nothing -- to do with the fact that Iraq has the second highest levels of oil reserves after Saudi Arabia and that global stocks of easily obtainable crude are diminishing.

If you believe that, of course, you'll believe anything. It beggars belief that an oil president from an oil state surrounded by former oil executives paid no heed to the West's strategic interests.

Certainly the idea that Saddam posed a threat to the West's economic security was a lot more credible than the notion that he posed a military threat.

And, naturally, there were sighs of relief all round when the immediate impact of war was positive for the global economy, prompting lower oil prices and a recovery in share prices and business confidence. Victory removed the uncertainties created by the long build-up to war.

Now it's a rather different story. Iraqi crude exports were disrupted earlier this month by sabotage to a pipeline carrying oil to the key loading terminal at Basra, target of failed suicide bomb attacks three weeks ago. There are fears about the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Saudi Arabia, the world's biggest oil producer and traditionally a staunch ally of Washington. Far from making oil supplies more secure, the events of the past 12 months have raised concerns that supplies could be disrupted at a time when global demand is high and rising. Limited supplies plus higher demand mean only one thing: prices go up. That's why crude is at US$40 a barrel.

Bush and Blair know their history. There have been three global recessions in the past 30 years, and all of them were pre-dated by a sharp rise in oil prices. Britain and the US may be able to weather the storm better this time because lower levels of inflation mean that there is less pressure to push interest rates up to cripplingly high levels, but there will still be a dampening effect on living standards and growth.

A second problem -- and this applies to the UK especially -- is that even before oil prices began to rise, the war in Iraq was crowding out good news on the economy. With a year to go before the possible date of the election, Labour ought to be banging on nonstop about last Wednesday's fall in jobless claimants to the lowest in almost 30 years and the longest period of sustained growth since the industrial revolution. Worryingly, a poll in The London Times earlier this month showed the economy well down the list of voter concerns. Even worse, the collapse in trust in the government over Iraq has spawned cynicism about claims that the extra billions spent on public services are making a difference. Given that investment in schools and hospitals was the centerpiece of Labour's domestic agenda for the second term, this is unhelpful, to say the least.

Up until now, however, the war has at least been kept discrete from the economy. Labour's strategists have comforted themselves that once the political agenda can be prised away from Iraq and on to "bread and butter" issues, the strength of the economy will prove decisive.

The nightmare scenario for Blair is that voters blame the mess in Iraq for higher prices at the petrol pumps, dearer air fares and -- depending on how policymakers respond to a rise in oil prices on inflation -- higher interest rates. Labour is expecting a pasting at next month's local and European elections, but will put defeat down to a protest vote. This argument will be tested fully over the coming months should oil prices remain at US$40 a barrel. If they do, recapturing support of lost voters will not be easy.

Larry Elliott is The Guardian's economics editor.

When US budget carrier Southwest Airlines last week announced a new partnership with China Airlines, Southwest’s social media were filled with comments from travelers excited by the new opportunity to visit China. Of course, China Airlines is not based in China, but in Taiwan, and the new partnership connects Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport with 30 cities across the US. At a time when China is increasing efforts on all fronts to falsely label Taiwan as “China” in all arenas, Taiwan does itself no favors by having its flagship carrier named China Airlines. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is eager to jump at

The muting of the line “I’m from Taiwan” (我台灣來欸), sung in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), during a performance at the closing ceremony of the World Masters Games in New Taipei City on May 31 has sparked a public outcry. The lyric from the well-known song All Eyes on Me (世界都看見) — originally written and performed by Taiwanese hip-hop group Nine One One (玖壹壹) — was muted twice, while the subtitles on the screen showed an alternate line, “we come here together” (阮作伙來欸), which was not sung. The song, performed at the ceremony by a cheerleading group, was the theme

Secretary of State Marco Rubio raised eyebrows recently when he declared the era of American unipolarity over. He described America’s unrivaled dominance of the international system as an anomaly that was created by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Now, he observed, the United States was returning to a more multipolar world where there are great powers in different parts of the planet. He pointed to China and Russia, as well as “rogue states like Iran and North Korea” as examples of countries the United States must contend with. This all begs the question:

In China, competition is fierce, and in many cases suppliers do not get paid on time. Rather than improving, the situation appears to be deteriorating. BYD Co, the world’s largest electric vehicle manufacturer by production volume, has gained notoriety for its harsh treatment of suppliers, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability. The case also highlights the decline of China’s business environment, and the growing risk of a cascading wave of corporate failures. BYD generally does not follow China’s Negotiable Instruments Law when settling payments with suppliers. Instead the company has created its own proprietary supply chain finance system called the “D-chain,” through which