"Become who you are," wrote Friedrich Nietzsche. A century later, millions of people are taking Nietzsche's advice to heart. But instead of turning to philosophy, they are using drugs and surgery.

"I feel like myself again on Paxil," says the woman in advertisements for that antidepressant; so, supposedly, do users of Prozac, Ritalin, Botox, Propecia, Xenical, anabolic steroids, cosmetic surgery, hormone replacement therapy and sex-reassignment surgery.

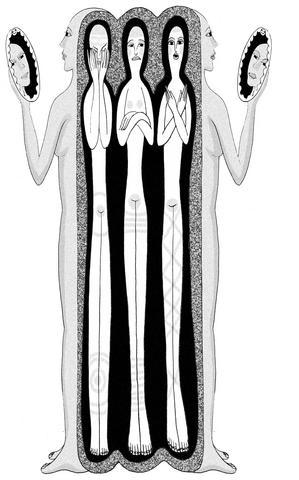

Even as people undergo dramatic self-transformations, altering their personalities with psychoactive drugs and their bodies with surgery, they describe the transformation as a matter of becoming "who they really are."

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

"It was only by using steroids," writes the bodybuilder Samuel Fussell, "that I looked on the outside the way I felt on the inside."

With sex-reassignment surgery, writes Jan Morris, "I achieved Identity at last."

If Nietzsche were alive today, he might be pitching antidepressants for Pfizer.

Many people nowadays do not expect to find the meaning of their lives by looking to God, truth, or any other external moral framework. Instead, they expect to find it by looking inward.

Being in touch with one's inner feelings, desires and aspirations is now seen as a necessary part of living a fully human life. To be fulfilled, you must be in touch with yourself.

The language of authenticity has come to feel like a natural way to describe our aspirations, our psychopathologies, even our self-transformations.

What is new is the involvement of doctors in fulfilling this desire for self-transformation. In recent decades, doctors have become much more comfortable giving physical treatments to remedy psychological and social problems.

Today, doctors give synthetic growth hormone to short boys, or Propecia to middle-aged men to remedy the shame of baldness. Now that the enhancement of psychological well-being is regarded by some as a proper medical goal, the range of potentially treatable conditions has expanded enormously.

Is the success of these technologies a problem? Not necessarily. Some drugs and procedures alleviate the darkest of human miseries. For every person using an anti-depressant to become "better than well," another is using it for a life-threatening sense of hopelessness.

If sex-reassignment surgery can relieve a person's suffering, then the question of whether or not it is treating a conventionally defined illness seems beside the point.

Yet remaining untroubled by all this medically induced self-transformation is hard.

One worry is about what the philosopher Margaret Olivia Little calls "cultural complicity." As difficult as we may find it to condemn individuals who use drugs and surgery to transform themselves in accordance with dominant aesthetic standards, on a social level these procedures compound the problems they are meant to fix.

The more Asians get plastic surgery to make their eyes look European, for example, the more entrenched will become the social norm that says Asian eyes are something to be ashamed of. The same goes for light skin, large breasts, gentile noses or a sparkling personality.

Market pressures compound this worry. For several years now, antidepressants have been the most profitable class of drugs in the US.

These antidepressants are not used simply to treat severe clinical depression. They are also widely used to treat social anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorders and sexual compulsions, as well as premenstrual-dysphoric disorder.

Many of these disorders were once thought to be rare, even non-existent. But once a pharmaceutical company develops a treatment for a psychiatric disorder, it acquires a financial interest in making sure that doctors diagnose the disorder as often as possible.

This may transform what was once seen as an ordinary human variation -- being shy, uptight or melancholy -- into a psychiatric problem.

The more people who are persuaded that they have a disorder that can be medicated, the more medication the company can sell.

Perhaps the hardest worry to pin down is what Harvard political theorist Michael Sandel calls "the drive to mastery." Sandel is worried less about the possible consequences of enhancement technologies than about the sensibility they reflect -- a sensibility that sees the world as something to be manipulated and controlled.

As Sandel points out, perhaps we could design a world in which we all have access to mood-brightening drugs and cosmetic surgery; in which athletes have access to safe, performance-enhancing drugs; in which we could safely choose and manipulate the genetic traits of our children; and in which we eat factory-farmed pigs and chickens that are genetically engineered not to feel pain.

Many of us would resist such a world -- not because such a world would be unjust, or because it would lead to more pain and suffering, but because of the extent to which it has been planned and engineered.

We would resist the idea that the world exists merely to be manipulated for human ends.

Carl Elliott teaches at the Center for Bioethics at the University of Minnesota and is a visiting professor at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University. He is the author of Better Than Well: American Medicine Meets the American Dream. Copyright: Project Syndicate

When US budget carrier Southwest Airlines last week announced a new partnership with China Airlines, Southwest’s social media were filled with comments from travelers excited by the new opportunity to visit China. Of course, China Airlines is not based in China, but in Taiwan, and the new partnership connects Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport with 30 cities across the US. At a time when China is increasing efforts on all fronts to falsely label Taiwan as “China” in all arenas, Taiwan does itself no favors by having its flagship carrier named China Airlines. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is eager to jump at

The muting of the line “I’m from Taiwan” (我台灣來欸), sung in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), during a performance at the closing ceremony of the World Masters Games in New Taipei City on May 31 has sparked a public outcry. The lyric from the well-known song All Eyes on Me (世界都看見) — originally written and performed by Taiwanese hip-hop group Nine One One (玖壹壹) — was muted twice, while the subtitles on the screen showed an alternate line, “we come here together” (阮作伙來欸), which was not sung. The song, performed at the ceremony by a cheerleading group, was the theme

Secretary of State Marco Rubio raised eyebrows recently when he declared the era of American unipolarity over. He described America’s unrivaled dominance of the international system as an anomaly that was created by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Now, he observed, the United States was returning to a more multipolar world where there are great powers in different parts of the planet. He pointed to China and Russia, as well as “rogue states like Iran and North Korea” as examples of countries the United States must contend with. This all begs the question:

In China, competition is fierce, and in many cases suppliers do not get paid on time. Rather than improving, the situation appears to be deteriorating. BYD Co, the world’s largest electric vehicle manufacturer by production volume, has gained notoriety for its harsh treatment of suppliers, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability. The case also highlights the decline of China’s business environment, and the growing risk of a cascading wave of corporate failures. BYD generally does not follow China’s Negotiable Instruments Law when settling payments with suppliers. Instead the company has created its own proprietary supply chain finance system called the “D-chain,” through which