Lingering at a day market for laborers in Panyu, an urban village on the outskirts of Guangzhou, Ms Qiu looks dejected. She is looking for a local factory that will hire her for the day to sew clothes — cheap tops and dresses that would be churned out onto China’s e-commerce platforms, or bundled up for export to western shoppers, but she is not having much luck.

“The whole industry is struggling, and now there is a high tariff on Chinese goods because of the trade war. Many foreign clients have decreased their orders from China,” she said, declining to give her first name.

Guangzhou, China’s southern metropolis and the capital of Guangdong Province, is home to nearly 20 million people. It is also the humming, whirring and buzzing heart of the global fast fashion industry.

Photo: AFP

In its urban villages, ramshackle settlements that have been absorbed into the city’s sprawl, millions of workers toil day and night in informal workshops to produce cheap garments.

In one small, crowded factory, women sit behind sewing machines next to teetering mountains of starched black tutus. In another, pink denim jeans destined to be sold on fast fashion Web site Shein are piled high on every available worktop.

Every morning, workers gather in informal labor markets like the one in Panyu to see if they can find work for the day sewing on hundreds of buttons or ironing hundreds of collars.

Photo: AFP

Depending on the complexity of the task, workers earn between one and 10 yuan (US$0.14 and US$1.39) per item, toiling for long hours in cramped conditions.

“This is hard-earned money,” said a worker in his 60s in Datang, another urban village about 16km north of Panyu. Ironing jackets at 8am, before packaging them up to be exported, the man, who declined to give his name, was partway through a shift that had started at 11pm the night before. He earned two yuan per jacket, he said.

More than a dozen garment workers said that a normal working day was 10 to 12 hours, with some saying they only took one rest day each month.

SMALLer PROFITS

While China’s domestic e-commerce market has boomed in the past few years, it is overseas orders that keep the factory lights on. About one-quarter of the more than US$100 billion of textiles and apparel imported to the US came from China last year.

Guangdong alone exported more than US$7 billion, according to data from the Global Trade & Industry Growth Lab by Sinoimex, a commercial data firm.

However, US President Donald Trump in April launched a trade war with China, which sent shockwaves through the global economy. Tariffs on Chinese goods reached 145 percent, with China responding with similar duties and trade restrictions, before the two countries agreed to a 90-day pause in May.

With an Aug. 12 deadline looming to reach a deal, workers in Guangzhou are wondering whether they will be able to keep selling clothes to Americans.

In Panyu, Yang Ruiping has run his small clothes factory, which specializes in tops and employs about 20 people, for two decades. About 30 percent of his orders are exported, mostly to Shein and Amazon, down from more than 50 percent before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although the pause in the trade war has eased the pressure on his business slightly, he still has “little confidence in the US.”

“In the recent US-China trade war, if the tariffs go up, we need to lower the production costs to combat it,” he said. “It leaves little room for profit.”

With no room to cut wages any lower, Yang said he is already losing money on every top he sells. He keeps accepting the orders to keep the factory open, but with the domestic market becoming increasingly competitive, he is aware he might not be able to operate much longer.

SHEIN

Shein is everywhere in Panyu. The China-founded, Singapore-headquartered company revolutionized the garment industry in Guangzhou, allowing small manufacturers like Yang to sell directly to Western customers and offering shoppers rock-bottom prices.

While big high street brands operate larger, dedicated factories, Shein places small batch orders directly with independent manufacturers, ramping up production for the designs that sell well online.

The flexibility of this model has fueled the company’s meteoric rise. Shein accounts for about 50 percent of the US fast fashion industry, according to Bloomberg Second Measure, a data analytics firm.

The company’s growth has also been driven by loopholes in the US customs regime, which allowed low-value goods to be imported free.

In 2022, more than 30 percent of all the small packages imported under the so-called de minimis exemption came from Shein and Temu, another Chinese e-commerce company. On May 2, Trump closed that loophole for goods from China and Hong Kong.

This week, he expanded that ban to goods from all countries, meaning that suppliers cannot avoid tariffs by shipping via third countries.

A recent analysis by Reuters found that prices on Shein increased by an average of 23 percent between April 24 and July 22.

The US market is “volatile and risky,” said Peng Jianshen, the boss of a medium-sized denim clothes factory in Zengcheng, another of Guangzhou’s urban villages.

“When tariffs were suddenly increased, the entire US-focused production stopped. No one dared to continue,” he said.

LOWER WAGES

Experts say that the uncertainty of the trade war could have a negative impact on working conditions, encouraging workers to add hours to their already punishingly long shifts.

“Generally, when we’re talking about the garment industry in China, workers don’t have rest days,” said Li Qiang (李強), founder of China Labor Watch, a US-based non-governmental organization. “They’re paid by piece rate. So they work as much as possible when the orders are still there.”

UKRAINE WAR

However, factory bosses in Guangzhou say the trade war is only the latest in a series of problems facing their industry. Global conflicts and low consumer spending in China mean that it is hard to pivot away from the US and toward other markets.

Li Jun, a chain-smoking factory boss, runs a denim clothing factory that sells jeans to Russia. He said the economic impact of the war in Ukraine, plus the fact that many of his would-be customers have been drafted to fight in the conflict, has been bad for business.

“The economy is not doing well anywhere,” he said. “A lot of factories are shutting down.”

At his peak, he was exporting 100,000 pairs of jeans per month, with more than half going to Russia, but now it is 30,000 to 40,000 pairs each month, meaning that he just about breaks even.

Manufacturers in places like Guangzhou have long been the engine room of China’s growth, but in recent years, keen to shed the label of being the world’s factory, Beijing has been pouring all its political and economic support into high-tech industries, such as artificial intelligence and semiconductors.

“The Chinese government no longer supports these kinds of light industries or small individual businesses,” Li said. “It’s really hard to keep things going.”

In Italy’s storied gold-making hubs, jewelers are reworking their designs to trim gold content as they race to blunt the effect of record prices and appeal to shoppers watching their budgets. Gold prices hit a record high on Thursday, surging near US$5,600 an ounce, more than double a year ago as geopolitical concerns and jitters over trade pushed investors toward the safe-haven asset. The rally is putting undue pressure on small artisans as they face mounting demands from customers, including international brands, to produce cheaper items, from signature pieces to wedding rings, according to interviews with four independent jewelers in Italy’s main

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has talked up the benefits of a weaker yen in a campaign speech, adopting a tone at odds with her finance ministry, which has refused to rule out any options to counter excessive foreign exchange volatility. Takaichi later softened her stance, saying she did not have a preference for the yen’s direction. “People say the weak yen is bad right now, but for export industries, it’s a major opportunity,” Takaichi said on Saturday at a rally for Liberal Democratic Party candidate Daishiro Yamagiwa in Kanagawa Prefecture ahead of a snap election on Sunday. “Whether it’s selling food or

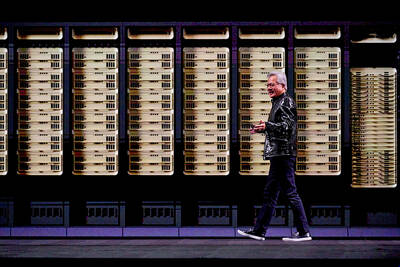

CONCERNS: Tech companies investing in AI businesses that purchase their products have raised questions among investors that they are artificially propping up demand Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Saturday said that the company would be participating in OpenAI’s latest funding round, describing it as potentially “the largest investment we’ve ever made.” “We will invest a great deal of money,” Huang told reporters while visiting Taipei. “I believe in OpenAI. The work that they do is incredible. They’re one of the most consequential companies of our time.” Huang did not say exactly how much Nvidia might contribute, but described the investment as “huge.” “Let Sam announce how much he’s going to raise — it’s for him to decide,” Huang said, referring to OpenAI

The global server market is expected to grow 12.8 percent annually this year, with artificial intelligence (AI) servers projected to account for 16.5 percent, driven by continued investment in AI infrastructure by major cloud service providers (CSPs), market researcher TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. Global AI server shipments this year are expected to increase 28 percent year-on-year to more than 2.7 million units, driven by sustained demand from CSPs and government sovereign cloud projects, TrendForce analyst Frank Kung (龔明德) told the Taipei Times. Demand for GPU-based AI servers, including Nvidia Corp’s GB and Vera Rubin rack systems, is expected to remain high,