In 28 years in India’s pharmaceuticals sector, Rajiv Desai has never been busier.

Most of the last six months on his desk calendar is marked green, indicating visits to the 12 plants of Lupin Pharmaceuticals Inc, India’s No. 2 drugmaker, where Desai is a senior quality control executive. Only one day is red — a day off.

That is what is needed these days to satisfy the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that standards are being met.

“In this sector, you’re only as good as your last inspection,” Desai said in his office in suburban Mumbai.

Often dubbed “the pharmacy of the world,” India is home to the most FDA-approved plants outside of the US and supplies about 40 percent of the US$70 billion worth of generic drugs sold in the country.

However, sanctions and bans have badly damaged India’s reputation and slowed growth in the US$16 billion sector. Drug exports fell in the fiscal year ending in March.

More than 40 plants have been banned by the FDA for issues ranging from data fraud to hygiene since India’s then-largest drugmaker Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd was pulled up for serious violations in 2008.

Drug companies have spent millions of dollars on training, new equipment and foreign consultants.

Yet the Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance of the top 20 firms says its members still need at least five more years to get manufacturing standards and data reliability up to scratch.

The case of Lupin shows why.

The FDA is in the next few months expected to clear Lupin’s Goa plant, which supplies around a third of its US sales, of problems found in 2015, Desai said.

However, the agency also published a new notice just last week citing issues with data storage at its plant in Pithampur, central India.

If companies want to continue to sell into the world’s biggest health care market, they must keep constant vigilance.

“A lot of companies will struggle to meet the requirements that are the need of the day, and I would expect to see additional consolidation on the supply side,” Lupin chief executive officer Vinita Gupta told analysts last month.

India has its own standards body, the Central Drug Standard Control Organization (CDSCO), which maintains that its quality controls are stringent enough to ensure drugs are safe.

“India’s standards are different,” Indian Drug Controller General and head of CDSCO G.N. Singh said in an interview in his New Delhi office. “Indian companies are compliant with our manufacturing standards. We cannot regulate them according to the US standards.”

The FDA has taken matters into its own hands and gradually expanded in India to more than a dozen full-time staff.

Inspections are frequent and increasingly unannounced. If the agency finds problems, it issues a Form 483 — a notice outlining the violations — which, if not resolved, can lead to a “warning letter” and in worst case, a ban.

Violations range from hygiene problems, such as rat traps and dirty laboratories, to inadequate controls on systems that store data, leaving it open to tampering.

None of the violations the FDA has cited in India have explicitly said the drugs are unsafe and when companies are banned by the FDA, they can sell into other markets, including in the developing world, until the bans are lifted.

Industry watchers say Lupin, which specializes in oral contraceptives and drugs for diabetes and hypertension, is doing better than most, as so far, none of its infractions have extended to a ban.

On a recent visit by reporters to its Goa plant, blue-uniformed employees could be seen working on giant machines, then making notes in hardbound registers. These are being phased out as Lupin transitions to more secure e-files.

Employees are often videotaped to ensure they follow standard operating procedure. Manufacturers have cut back to focus on quality over quantity: Five years ago, Lupin was making 1 billion pills a month at one of its Goa plants — now it makes just 450 million.

Both the company and employees needed to be willing to acknowledge errors, as the first impulse in the past was often “don’t tell anyone,” Desai said.

As recently as three years ago, training was a “formality,” Desai said. Now, when an error is traced to an employee, the entire team undergoes fresh training.

The companies also have to be willing to spend big. Lachman Consultants, PwC and Boston Consulting Group conduct mock audits at the Goa plant every three to six months, at a cost of up to US$400 an hour.

DIVIDED VIEWS: Although the Fed agreed on holding rates steady, some officials see no rate cuts for this year, while 10 policymakers foresee two or more cuts There are a lot of unknowns about the outlook for the economy and interest rates, but US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell signaled at least one thing seems certain: Higher prices are coming. Fed policymakers voted unanimously to hold interest rates steady at a range of 4.25 percent to 4.50 percent for a fourth straight meeting on Wednesday, as they await clarity on whether tariffs would leave a one-time or more lasting mark on inflation. Powell said it is still unclear how much of the bill would fall on the shoulders of consumers, but he expects to learn more about tariffs

Meta Platforms Inc offered US$100 million bonuses to OpenAI employees in an unsuccessful bid to poach the ChatGPT maker’s talent and strengthen its own generative artificial intelligence (AI) teams, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has said. Facebook’s parent company — a competitor of OpenAI — also offered “giant” annual salaries exceeding US$100 million to OpenAI staffers, Altman said in an interview on the Uncapped with Jack Altman podcast released on Tuesday. “It is crazy,” Sam Altman told his brother Jack in the interview. “I’m really happy that at least so far none of our best people have decided to take them

PLANS: MSI is also planning to upgrade its service center in the Netherlands Micro-Star International Co (MSI, 微星) yesterday said it plans to set up a server assembly line at its Poland service center this year at the earliest. The computer and peripherals manufacturer expects that the new server assembly line would shorten transportation times in shipments to European countries, a company spokesperson told the Taipei Times by telephone. MSI manufactures motherboards, graphics cards, notebook computers, servers, optical storage devices and communication devices. The company operates plants in Taiwan and China, and runs a global network of service centers. The company is also considering upgrading its service center in the Netherlands into a

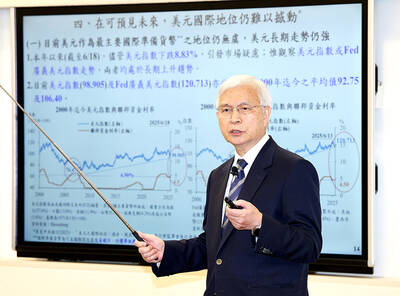

NOT JUSTIFIED: The bank’s governor said there would only be a rate cut if inflation falls below 1.5% and economic conditions deteriorate, which have not been detected The central bank yesterday kept its key interest rates unchanged for a fifth consecutive quarter, aligning with market expectations, while slightly lowering its inflation outlook amid signs of cooling price pressures. The move came after the US Federal Reserve held rates steady overnight, despite pressure from US President Donald Trump to cut borrowing costs. Central bank board members unanimously voted to maintain the discount rate at 2 percent, the secured loan rate at 2.375 percent and the overnight lending rate at 4.25 percent. “We consider the policy decision appropriate, although it suggests tightening leaning after factoring in slackening inflation and stable GDP growth,”