Apple Inc is on the verge of doing what few others have: Change the English language.

When you have a boo-boo, you reach for a Band-Aid, not a bandage. When you need to blow your nose, you ask for Kleenex, not tissues. If you decide to look up something online, you Google instead of search for it. And if you want to buy a tablet computer, there’s a good chance there’s only one name you’ll remember.

“For the vast majority, the idea of a tablet is really captured by the idea of an iPad,”’ says Josh Davis, a manager at Abt Electronics in Chicago. “They gave birth to the whole category and brought it to life.”

Companies trip over themselves to make their brands household names, but only a few brands become so engrained in the lexicon that they’re synonymous with the products themselves. This so-called “genericization” can be both good and bad for companies like Apple, which must balance its desire for brand recognition with its disdain for brand deterioration.

It’s one of the biggest contradictions in business. Companies spend millions to create a brand. Then, they spend millions more on marketing that can have the unintended consequence of making those names so popular that they become shorthand for similar products. It’s like if people start calling station wagons Bentleys. It can diminish a brand’s reputation.

“There’s tension between legal departments concerned about ‘genericide’ and marketing departments concerned about sales,” says Michael Atkins, a Seattle trademark attorney. “Marketing people want the brand name as widespread as possible and trademark lawyers worry ... the brand will lose all trademark significance.”

It doesn’t happen often. In fact, it’s estimated that fewer than 5 percent of US brand names become generic. Those that do typically are inventions or products that improve on what’s already on the market. The brand names then become so popular that they eclipse rivals in sales, market share and in the minds’ of consumers. And then they spread through the English language like the common cold in a small office.

“There’s nothing that can be done to prevent it once it starts happening,” says Michael Weiss, professor of linguistics at Cornell University. “There’s no controlling the growth of language.”

A company’s biggest fear is that its brand name becomes so commonly used to describe a product that a judge rules that it’s too “generic” to be a trademark. That means that any product — even inferior ones — can legally use the name. A brand is usually declared legally generic after a company sues another firm for using its name and the case goes to a federal court.

Drug maker Bayer lost trademarks for the names “aspirin” and “heroin” this way in the 1920s. So did B.F. Goodrich, which sued to protect its trademark of “zipper” in the 1920s after the name joined the world of common nouns. Similar cases deemed “escalator” generic in 1950, “thermos” generic in 1963 and “yo-yo” generic in 1965.

It’s difficult to quantify how much revenue a company loses when its brand is deemed generic. However, companies worry that it breeds confusion among consumers.

To prevent their names from becoming generic, some companies use marketing to reinforce their trademarks. For instance, after its Band-Aid brand name started becoming commonly used to refer to adhesive bandages, Johnson & Johnson changed its jingle in ads from “I’m stuck on Band-Aid” to “I’m stuck on Band-Aid brand.”

Kleenex uses “Kleenex brand” instead of just “Kleenex” on its packaging and in marketing, and places ads to remind people Kleenex is trademarked. The company also contacts some people who use Kleenex generically to refer to tissue to correct them.

Xerox is taking a similar route. The company, which introduced the first automatic copier in the US in 1959, has been on a public crusade for decades to keep its brand from becoming generic. The machine’s success has led people to start using “Xerox” to refer to any copying machine, copies made from one and the act of copying.

“In the mid to late-1970s, we ran dangerously close to Xerox becoming genericized,” says Barbara Basney, vice president of global advertising. “That prompted a lot of proactive action to protect our trademark.”

Xerox has spent millions taking out ads aimed at educating so-called “influencers” like lawyers, journalists and entertainers about its brand name. A 2003 ad said: “When you use ‘Xerox’ the way you use ‘aspirin,’ we get a headache.” More recently, a 2007 ad read: “If you use ‘Xerox’ the way you use ‘zipper,’ our trademark could be left wide open.”

While people still use “Xerox” generically — the Merriam-Webster dictionary lists the word as both a lower-case verb with the definition “to copy on a xerographic copier” and a trademarked noun — the brand says its campaign has been a success.

Xerox is still popular: It’s ranked the 57th-most valuable global brand, worth US$6.4 billion, according to brand consultancy Interbrand. And perhaps most importantly, Xerox hasn’t lost its trademark.

Sometimes companies embrace when their brands become common nouns.

Perhaps the best example of this is Google, a company created in 1998 when Alta Vista and Yahoo.com were the top online search engines. Google, which created a formula that returned more accurate results than its competitors, became so popular that people began saying “Google” to refer to a Web search in general. Experts say Google has benefited from its name becoming a part of the lexicon.

“You don’t say ‘Why don’t I Google it’ and go to Yahoo or Bing,” says Jessica Litman, professor of copyright law at the University of Michigan Law School, referring to other search engines.

Apple also has gotten a boost from its brand names becoming synonymous with products. The iPod, which was the first digital music player when it came out in 2001, is still the name people use for “digital music player” or “MP3 player.” And it appears Apple’s iPad is headed down the same path.

For consumers like Mary Schmidt, 58, the “iPad” is generic for “tablet.” Schmidt, a Baltimore marketing executive, owns an iPad and doesn’t know the names of any other tablets.

“When I think of tablets, I think of an iPad,” she says. “I think it’s going to be the generic name. They were first.”

It remains to be seen if the iPad will maintain its name domination in the tablet market. Apple declined to comment for this article.

For now, Apple has a majority of the tablet category, which includes Amazon’s Kindle Fire and Samsung Electronics Co’s Galaxy Tablet. The iPad accounted for about 73 percent of the estimated 63.6 million tablets sold globally last year, according to research firm Gartner.

Apple’s market share is likely to decline as more rivals roll out tablets, but experts say that won’t necessarily diminish iPad’s name recognition.

“Apple is actually pretty good at this,” Litman says. “It’s able to skate pretty close to the generics line while making it very clear the name is a trademark of the Apple version of this general category.”

When the iPad debuted in 2010, some people offered up “Apple Tablet” or the “iTab” as better names. Others even suggested that the name sounded more like a feminine hygiene product than a tablet: “Get ready for Maxi pad jokes and lots of ‘em!” tech site Gizmodo wrote at the time.

Two years later, those complaints are all but forgotten.

“At the end of the day, the product was so successful that even if it wasn’t the ‘quote unquote’ best name, it made the name synonymous with the category,” says Allen Adamson, managing director at branding firm Landor.

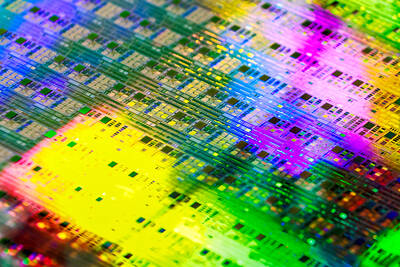

SEMICONDUCTOR SERVICES: A company executive said that Taiwanese firms must think about how to participate in global supply chains and lift their competitiveness Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) yesterday said it expects to launch its first multifunctional service center in Pingtung County in the middle of 2027, in a bid to foster a resilient high-tech facility construction ecosystem. TSMC broached the idea of creating a center two or three years ago when it started building new manufacturing capacity in the US and Japan, the company said. The center, dubbed an “ecosystem park,” would assist local manufacturing facility construction partners to upgrade their capabilities and secure more deals from other global chipmakers such as Intel Corp, Micron Technology Inc and Infineon Technologies AG, TSMC said. It

NO BREAKTHROUGH? More substantial ‘deliverables,’ such as tariff reductions, would likely be saved for a meeting between Trump and Xi later this year, a trade expert said China launched two probes targeting the US semiconductor sector on Saturday ahead of talks between the two nations in Spain this week on trade, national security and the ownership of social media platform TikTok. China’s Ministry of Commerce announced an anti-dumping investigation into certain analog integrated circuits (ICs) imported from the US. The investigation is to target some commodity interface ICs and gate driver ICs, which are commonly made by US companies such as Texas Instruments Inc and ON Semiconductor Corp. The ministry also announced an anti-discrimination probe into US measures against China’s chip sector. US measures such as export curbs and tariffs

The US on Friday penalized two Chinese firms that acquired US chipmaking equipment for China’s top chipmaker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC, 中芯國際), including them among 32 entities that were added to the US Department of Commerce’s restricted trade list, a US government posting showed. Twenty-three of the 32 are in China. GMC Semiconductor Technology (Wuxi) Co (吉姆西半導體科技) and Jicun Semiconductor Technology (Shanghai) Co (吉存半導體科技) were placed on the list, formally known as the Entity List, for acquiring equipment for SMIC Northern Integrated Circuit Manufacturing (Beijing) Corp (中芯北方積體電路) and Semiconductor Manufacturing International (Beijing) Corp (中芯北京), the US Federal Register posting said. The

India’s ban of online money-based games could drive addicts to unregulated apps and offshore platforms that pose new financial and social risks, fantasy-sports gaming experts say. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government banned real-money online games late last month, citing financial losses and addiction, leading to a shutdown of many apps offering paid fantasy cricket, rummy and poker games. “Many will move to offshore platforms, because of the addictive nature — they will find alternate means to get that dopamine hit,” said Viren Hemrajani, a Mumbai-based fantasy cricket analyst. “It [also] leads to fraud and scams, because everything is now