Flanked by green cricket fields where he once played and a university from which he graduated, Arvind Vaghela tries not to notice the stream of students walking past. "I used to be like them, attending lectures and going out on the fields. But now I just hide my face," he said.

The reason for his shame is the broom in his hand. Despite a masters degree in economics from Gujarat University in Ahmedabad, the best job Vaghela, 24, could get was one done by generations of his family: roadsweeper.

"I wanted to work in sales for a bank, but you needed to have your own vehicle. I come from a poor family, so how could I afford that? When my father died I was offered his job and I took it," he said.

As a Dalit, or untouchable, Vaghela's story is familiar in this sprawling west Indian city. Nearly 100 of its council sanitation workers have degrees in subjects ranging from computing to law, but cannot get better jobs because they are Dalits.

Their experience is part of an increasingly heated debate in India, where the government has announced that it will consider extending public-sector job quotas for people from the lowest castes to the private sector.

Industrialists, who insist private-sector jobs and promotions are earned on merit, say that this will make businesses inefficient and uncompetitive.

Rahul Bajaj, who chairs a large motorcycle manufacturer, wrote in the Times of India that public-sector job quotas had reduced the "effectiveness of government" because decisions were not made on the basis of ability.

This argument leaves Ahmedabad's roadsweeping graduates unimpressed. Most say that they have had to face discrimination or exploitation in the private sector.

"I got a job with a firm of accountants and then had to present my qualifications. On one school certificate it mentioned my caste.

"The next day I was told there had been a mistake -- I was not required any more," said Dalit sweeper Prakash Chauhan, 32, who has a a degree in commerce.

Chauhan stresses he is relatively well paid, at 4,000 rupees (US$87) a month, and his job is secure.

"This is a job for life. But it was my father's life. Our parents had a dream that education would mean we would not have to do the jobs they did. It did not turn out that way," he said.

Dalits, the lowest caste, have endured centuries of discrimination and violence because of a social order that consigns them and their descendants to jobs nobody else wants and a tradition that all humans are created unequal.

In rural India Dalits have been murdered for proposing to marry somebody further up the social ladder, barred from temples, forced into bonded labor and made to carry human waste from the homes of high-caste Hindus.

In the cities, where it is easier to change one's name and slip into the crowd, Dalits say economic exclusion is now the biggest issue.

The ingrained unfairness of the caste system has brought pressure for reform on human rights grounds against Western firms doing business in India. Unions have written to 300 companies in Europe which outsource work to India to check that their subcontractors do not discriminate on the basis of caste.

"There are many parallels with the situation in South Africa in the [1960s], when foreign companies needed to be persuaded to address the discrimination in the system of apartheid,' said David Haslam, the London-based chair of the Dalit Solidarity Network.

Chandra Bhan Prasad, a Dalit writer, says businesses should look for inspiration to the US, where firms carry out diversity audits and give contracts to firms from minority groups.

NOT JUSTIFIED: The bank’s governor said there would only be a rate cut if inflation falls below 1.5% and economic conditions deteriorate, which have not been detected The central bank yesterday kept its key interest rates unchanged for a fifth consecutive quarter, aligning with market expectations, while slightly lowering its inflation outlook amid signs of cooling price pressures. The move came after the US Federal Reserve held rates steady overnight, despite pressure from US President Donald Trump to cut borrowing costs. Central bank board members unanimously voted to maintain the discount rate at 2 percent, the secured loan rate at 2.375 percent and the overnight lending rate at 4.25 percent. “We consider the policy decision appropriate, although it suggests tightening leaning after factoring in slackening inflation and stable GDP growth,”

DIVIDED VIEWS: Although the Fed agreed on holding rates steady, some officials see no rate cuts for this year, while 10 policymakers foresee two or more cuts There are a lot of unknowns about the outlook for the economy and interest rates, but US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell signaled at least one thing seems certain: Higher prices are coming. Fed policymakers voted unanimously to hold interest rates steady at a range of 4.25 percent to 4.50 percent for a fourth straight meeting on Wednesday, as they await clarity on whether tariffs would leave a one-time or more lasting mark on inflation. Powell said it is still unclear how much of the bill would fall on the shoulders of consumers, but he expects to learn more about tariffs

Greek tourism student Katerina quit within a month of starting work at a five-star hotel in Halkidiki, one of the country’s top destinations, because she said conditions were so dire. Beyond the bad pay, the 22-year-old said that her working and living conditions were “miserable and unacceptable.” Millions holiday in Greece every year, but its vital tourism industry is finding it harder and harder to recruit Greeks to look after them. “I was asked to work in any department of the hotel where there was a need, from service to cleaning,” said Katerina, a tourism and marketing student, who would

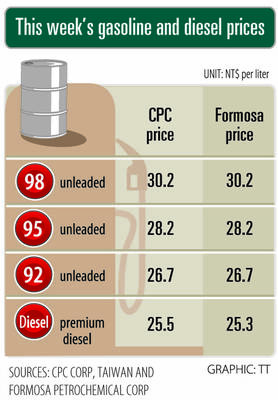

i Gasoline and diesel prices at fuel stations are this week to rise NT$0.1 per liter, as tensions in the Middle East pushed crude oil prices higher last week, CPC Corp, Taiwan (台灣中油) and Formosa Petrochemical Corp (台塑石化) said yesterday. International crude oil prices last week rose for the third consecutive week due to an escalating conflict between Israel and Iran, as the market is concerned that the situation in the Middle East might affect crude oil supply, CPC and Formosa said in separate statements. Front-month Brent crude oil futures — the international oil benchmark — rose 3.75 percent to settle at US$77.01