The nation's biggest brokerage firms have agreed to pay almost US$1 billion in fines to end investigations into whether they issued misleading stock recommendations and handed out hot new shares to curry favor with corporate clients, people involved in the negotiations said Thursday.

The firms have also agreed to sweeping changes in the way research is done on Wall Street and the way new stocks are distributed, moving away from the practices they used during the stock boom of the 1990s.

PHOTO: AP

As part of the settlement, which is expected to be announced Friday, the firms will pay an additional US$500 million over five years to buy stock research from independent analysts and distribute it to investors. The agreement is not final, but regulators were rushing Thursday to prepare an announcement to put an encouraging cap on a year fraught with corporate scandal.

The agreement is a result of roughly five months of fractious negotiations between the firms and securities regulators. It is intended to force Wall Street to produce honest stock research and to protect analysts from pressure within the firm to issue upbeat forecasts to attract investment banking fees. Under the terms of the deal, brokerage firms will also be barred from dispensing hot stocks to top executives or directors of public companies.

The broad agreement does not include the punishment of any Wall Street analysts or executives who supervised them, though state and national regulators may still pursue investigations of some analysts. That means Sanford I. Weill, the chairman of Citigroup, would not be charged with any violations of securities laws under the agreement. Weill has said that he asked Jack Grubman, who was a star analyst at Citigroup, to take a fresh look at his negative rating on AT&T stock in 1999.

Eyeing grubman

Grubman, who has been criticized as being too cozy with corporate clients, may still be punished. Regulators plan to fine him more than US$10 million and bar him from the securities industry for life in a separate settlement, people involved in the investigations said.

"The objective throughout this investigation has been to protect small investors by ensuring integrity in the marketplace," said Eliot Spitzer, the attorney general of New York, who was a lead negotiator of the settlement. "Hopefully, the rules that are embodied in this potential settlement will restore investor confidence by restoring integrity to the marketplace."

Regulators may not provide much more evidence of wrongdoing until the settlement is officially drawn up next year.

In agreeing to the fines, the firms would neither admit nor deny charges that they had misled investors. It is not clear how much of the fines will go to a restitution fund for investors.

The money will be split about evenly between the national regulators and the states. Half the proceeds will go to the national regulators, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the NASD and the New York Stock Exchange. The states will divide their share of the proceeds using a formula based largely on population.

Christine A. Bruenn, president of the North American Securities Administrators Association, said Thursday night: "We're very, very close to a resolution of these matters. A settlement will help restore faith in our markets if it changes the corporate culture, metes out meaningful penalties, gives investors independent research and the facts that they need."

Restitution fund

Under the corporate governance law passed this year, fines collected by the SEC must go to a restitution fund. But state regulators argue that it is too difficult to determine exactly who is owed restitution relating to research offenses. They say that some of the money may go toward investor education, but much of it may go into states' treasuries.

"It would be nice if some of the more egregious violators were punished," said Alan R. Bromberg, a professor of corporate and securities law at Southern Methodist University. Bromberg said he was disappointed that investors would not recoup more from the firms.

"To an extent, it's always individuals who are responsible for wrongdoing," Bromberg said. "This sort of settlement smooths that over so there's only corporate or institutional responsibility, not individual responsibility."

The expected settlement came roughly a year and a half after Spitzer began to uncover deep conflicts of interest in Wall Street research. Some analysts recommended stocks to investors not because of their prospects but because the analysts could share in the investment banking fees that the rosy research helped generate. Investigators from other regulatory organizations later joined Spitzer in putting Wall Street practices under the microscope.

Individual investors, meanwhile, were relying heavily on the research coming out of Wall Street firms, not knowing that much of it was biased. Individuals were typically shut out of new stock offerings and could buy such shares only after they had risen significantly in price.

As a result, dubious research and preferential treatment in the allocation of hot new shares contributed to vast losses by individual investors in the sharp stock market fall of the last two and a half years. Revelations about the nature and extent of the unfair practices have led to a significant decline in investor confidence in the financial markets.

Under the settlement, the type of selling activities that had become a large part of an analyst's job during the stock market mania will be curtailed. Analysts will no longer be allowed to helpsell stocks their firms are underwriting by accompanying investment bankers to meetings with investors. Neither will analysts' services be included in pitches made by their firms to companies hoping to sell shares or bonds to the public.

Bank pressure

In addition, a firm's investment bankers will be barred from putting pressure on analysts to change their views on a company. Bankers will not be involved in analysts' performance reviews or in discussions relating to their compensation. The firms will have to designate individuals in their legal and compliance departments to monitor the interaction between analysts and their colleagues in other departments.

To ensure that the principals abide by the terms of the settlement, regulators will conduct examinations of each firm beginning 18 months from now.

Each firm covered by the agreement will pay US$5 million to US$15 million annually for five years to obtain stock research from at least three sources that have no ties to an investment bank, people involved in the negotiations said. The firms would have to make those alternative views available to their customers by highlighting them in their regular communications, these people said.

The selection and purchase of the outside research would be overseen at each firm by an independent monitor appointed by regulators, they said. To improve transparency of their own investment recommendations, the big Wall Street firms would have to make their research available on their Web sites within 90 days of original publication, they said.

Some brokerage firms have agreed to pay larger fines than others and to pay different amounts for independent research and investor education. The final numbers were still being negotiated as late as Thursday night and could still change, people involved in the talks said.

The Salomon Smith Barney unit of Citigroup will pay the largest fine: US$325 million. Grubman, the firm's former telecommunications analyst, has been sued by NASD over his recommendations on the stock of a corporate client, Winstar Communications. He is also the subject of intense scrutiny for his unceasing support for companies whose stocks and bonds Salomon had underwritten but that in most cases lost almost all of their value. A spokesman for Grubman declined to comment Thursday night on any settlement talks.

Credit Suisse First Boston, a powerhouse in technology investment banking and research during the late 1990s, will pay US$150 million. Merrill Lynch has already paid a US$100 million fine to the states.

Seven other firms have agreed to pay about US$50 million each. They are Bear Stearns, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase, Lehman Brothers, Morgan Stanley and UBS Warburg. Two smaller firms, US Bancorp Piper Jaffray and Thomas Weisel Partners, have tentatively agreed to pay a combined US$50 million, people close to the negotiations said.

Including the money already paid by Merrill, the total of fines paid by the firms covered in the settlement rises to US$975 million.

The settlement is the second instance in less than a decade that Wall Street firms have agreed to pay about US$1 billion to settle regulatory charges of anti-investor practices. In 1997, about 30 brokerage firms and NASDAQ agreed to pay about US$1 billion to settle an investor lawsuit that they had colluded to keep costs unnaturally high in the trading of NASDAQ stocks.

But that case was overseen by federal investigators at the SEC and the Justice Department, while the investigation into Wall Street research was begun by Spitzer, a state official. Indeed,federal regulators seemed late to recognize the severity of the conflicts among Wall Street analysts and joined in the investigation only this year, after Spitzer released e-mail messages written by Merrill Lynch analysts that showed them privately deriding some of the same companies whose shares they were recommending to the public. Investigators subsequently released damaging e-mails messages written by analysts at Salomon Smith Barney and Credit Suisse First Boston.

In settling with the SEC, NASD, the New York attorney general and other state regulators, the 12 firms hope to put an end to the drumbeat of disclosures about dubious conduct that has damaged their reputations among investors.

The shift that transformed many research analysts into stock salespeople became most intense during the stock market bubble of the late 1990s, when Wall Street firms were generating enormous fees helping startup and established companies issue new shares or debt.

STARS were born

Analysts, who had previously worked in the background assessing companies' financial positions and business prospects, became stars in their own right, touting shares of companies they followed on television and in other media.

As the shares rose, so did analysts' credibility among investors and their power within the firms. Soon analysts were making millions of dollars a year, with a good part of their compensation coming from investment banking deals they helped bring to their firms.

But after the frenzied stock market peaked in March 2000, investors began to be suspicious of analysts' unrelenting bullishness on companies whose shares were plummeting. Last April, when Spitzer released the Merrill Lynch e-mails, investors began to see how promotional and prone to conflict stock analysts had become during the mania.

"The most notable achievement of Mr. Spitzer was publicizing these abuses," said John Coffee, a professor of law at Columbia University. "No firm could continue to maintain that there was value in securities research once he was waving their e-mails around.

"We can't say there won't again be bubbles," Coffee said. "But we've convinced investors that they cannot rely on gurus."

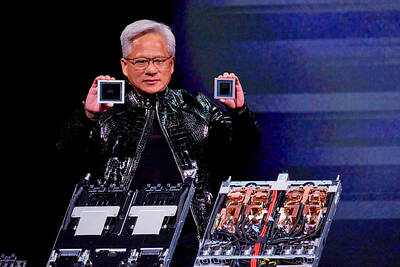

Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Monday introduced the company’s latest supercomputer platform, featuring six new chips made by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), saying that it is now “in full production.” “If Vera Rubin is going to be in time for this year, it must be in production by now, and so, today I can tell you that Vera Rubin is in full production,” Huang said during his keynote speech at CES in Las Vegas. The rollout of six concurrent chips for Vera Rubin — the company’s next-generation artificial intelligence (AI) computing platform — marks a strategic

REVENUE PERFORMANCE: Cloud and network products, and electronic components saw strong increases, while smart consumer electronics and computing products fell Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (鴻海精密) yesterday posted 26.51 percent quarterly growth in revenue for last quarter to NT$2.6 trillion (US$82.44 billion), the strongest on record for the period and above expectations, but the company forecast a slight revenue dip this quarter due to seasonal factors. On an annual basis, revenue last quarter grew 22.07 percent, the company said. Analysts on average estimated about NT$2.4 trillion increase. Hon Hai, which assembles servers for Nvidia Corp and iPhones for Apple Inc, is expanding its capacity in the US, adding artificial intelligence (AI) server production in Wisconsin and Texas, where it operates established campuses. This

Garment maker Makalot Industrial Co (聚陽) yesterday reported lower-than-expected fourth-quarter revenue of NT$7.93 billion (US$251.44 million), down 9.48 percent from NT$8.76 billion a year earlier. On a quarterly basis, revenue fell 10.83 percent from NT$8.89 billion, company data showed. The figure was also lower than market expectations of NT$8.05 billion, according to data compiled by Yuanta Securities Investment and Consulting Co (元大投顧), which had projected NT$8.22 billion. Makalot’s revenue this quarter would likely increase by a mid-teens percentage as the industry is entering its high season, Yuanta said. Overall, Makalot’s revenue last year totaled NT$34.43 billion, down 3.08 percent from its record NT$35.52

PRECEDENTED TIMES: In news that surely does not shock, AI and tech exports drove a banner for exports last year as Taiwan’s economic growth experienced a flood tide Taiwan’s exports delivered a blockbuster finish to last year with last month’s shipments rising at the second-highest pace on record as demand for artificial intelligence (AI) hardware and advanced computing remained strong, the Ministry of Finance said yesterday. Exports surged 43.4 percent from a year earlier to US$62.48 billion last month, extending growth to 26 consecutive months. Imports climbed 14.9 percent to US$43.04 billion, the second-highest monthly level historically, resulting in a trade surplus of US$19.43 billion — more than double that of the year before. Department of Statistics Director-General Beatrice Tsai (蔡美娜) described the performance as “surprisingly outstanding,” forecasting export growth