At the end of one of the most bizarre weather years in US history, climate research stands at a crossroads.

After extreme weather events like the drought in Texas and the floods in New England, scientists say they could, in theory, do a much better job of answering the question: “Did global warming have anything to do with it?”

However, for many reasons, efforts to put out prompt reports on the causes of extreme weather are essentially languishing. Chief among the difficulties that scientists face is that the political environment for new climate-science initiatives has turned hostile and, with the federal budget crisis, money is tight.

Photo: EPA

So, as the weather becomes more erratic by the year, the public is left to wonder what is going on.

When last year ended, it had seemed as if people had lived through a startling year of weather extremes, but in the US, if not elsewhere, this year has surpassed that.

A typical year in the US features three or four weather disasters whose costs exceed US$1 billion each, but this year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has tallied a dozen such events, including wildfires in the Southwest, floods in multiple regions of the country and a deadly spring tornado season — and the agency has not finished counting. The final costs are certain to exceed US$50 billion.

Photo: EPA

“I’ve been a meteorologist 30 years and never seen a year that comes close to matching 2011 for the number of astounding, extreme weather events,” Jeffrey Masters, a co-founder of the popular Web site Weather Underground, said last month. “Looking back in the historical record, which goes back to the late 1800s, I can’t find anything that compares, either.”

Many of the individual events this year do have precedents in the historical record and the nation’s climate has featured other concentrated periods of extreme weather, including severe cold snaps in the early 20th century and devastating droughts and heat waves in the Dust Bowl era of the 1930s.

However, it is unusual — if not unprecedented — for so many extremes to occur in such a short span. This year’s calamities included wildfires that scorched millions of acres, extreme flooding in the Upper Midwest and the Mississippi River valley and heat waves that shattered records in many parts of the country. Elsewhere, huge floods inundated Australia, the Philippines and large parts of Southeast Asia.

Photo: EPA

A major question nowadays is whether the frequency of particular weather extremes is being affected by human-induced climate change.

Climate science already offers some insight. Researchers have proved that the temperature of the earth’s surface is rising, and they are virtually certain that the human release of greenhouse gases, mainly from the burning of fossil fuels, is the major reason. For decades, they have predicted that this would lead to changes in the frequency of extreme weather events and statistics show that has begun to happen.

For instance, scientists have long expected that a warming atmosphere would result in fewer extremes of low temperature and more extremes of high temperature. In fact, research shows that about two record highs are being set in the US for every record low and similar trends can be detected in other parts of the world.

Likewise, a well-understood physical law suggests that a warming atmosphere should hold more moisture. Scientists have directly measured the moisture in the air and confirmed that it is rising, supplying the fuel for heavier rains, snowfalls and other types of storms.

“We are changing the large-scale properties of the atmosphere — we know that beyond a shadow of a doubt,” said Benjamin Santer, a leading climate scientist who works at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. “You can’t engage in this vast planetary experiment — warming the surface, warming the atmosphere, moistening the atmosphere — and have no impact on the frequency and duration of extreme events.”

If the human contribution to heat and precipitation is clear, scientists are on shakier ground analyzing many other events. Tornadoes, the deadliest weather disaster to hit the US this year, present a particularly thorny case.

On their face, weather statistics suggest that tornadoes are becoming more numerous as the climate warms, but tornadoes are small and hard to count and scientists have little confidence in the accuracy of older data, which means they do not know whether to believe the apparent increase. Likewise, the computer programs they use to analyze and forecast the climate do not do a good job of representing events as small as tornadoes.

Some scientists have offered theories about how increasing heat and moisture could have made tornado outbreaks more likely, but these have not yet been tested in rigorous analyses. Many other types of extreme weather fall into this category, with scientists lacking a strong basis for either attributing increases to human activity or discounting a human effect.

Some questions can be answered with focused studies of a specific weather event, but these are often finished years afterward. Lately, scientists have been discussing whether they can do a better job of analyzing events within days or weeks, not years.

“It’s clear we do have the scientific tools and the statistical wherewithal to begin answering these types of questions,” Santer said.

However, doing this on a regular basis would probably require new personnel spread across several research teams, along with a strong push by the federal government, which tends to be the major source of financing and direction for climate and weather research. Yet Washington is essentially frozen on the subject of climate change.

This year, when the NOAA tried to push through a reorganization that would have provided better climate forecasts to businesses, citizens and local governments, Republicans in the US House of Representatives blocked it. The idea originated in the administration of former US president George W. Bush, was strongly endorsed by an outside review panel and would have cost no extra money, but the House Republicans, many of whom reject the overwhelming scientific consensus about the causes of global warming, labeled the plan an attempt by the administration of US President Barack Obama to start a “propaganda” arm on climate.

In an interview, Jane Lubchenco, the director of the NOAA, rejected that claim and said her agency had been deluged with information requests regarding future climate risks.

“It’s truly unfortunate that we are not allowed to become more effective and efficient in delivering that information,” she said.

The NOAA does finance research to understand the causes of weather extremes, as do the National Science Foundation and the US Department of Energy. However, with the strains on the federal budget, Lubchenco said, “it’s going to be more and more challenging to devote resources to many of our research programs.”

Some steps are being taken. Peter Stott, a leading climate scientist in Britain, has been pressing colleagues on both sides of the Atlantic to develop a robust capability to analyze weather extremes in real time. He is part of a group that expects to publish in summer the first complete analysis of a full year of extremes, focusing on this year.

In an interview, Stott said the goal was to get to a point where “the methodologies are robust enough that you can do it in a kind of handle-turning way.”

However, he added that it was important to start slowly and establish a solid scientific foundation for this type of work. That might mean that some of the early analyses would not be especially satisfying to the public.

“In some cases, we would say we have a confident result,” Stott said. “We may in some cases have to say, with the current state of the science, it’s not possible to make a reliable attribution statement at this point.”

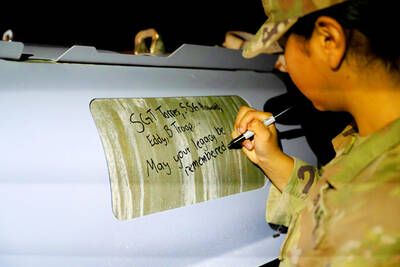

REVENGE: Trump said he had the support of the Syrian government for the strikes, which took place in response to an Islamic State attack on US soldiers last week The US launched large-scale airstrikes on more than 70 targets across Syria, the Pentagon said on Friday, fulfilling US President Donald Trump’s vow to strike back after the killing of two US soldiers. “This is not the beginning of a war — it is a declaration of vengeance,” US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth wrote on social media. “Today, we hunted and we killed our enemies. Lots of them. And we will continue.” The US Central Command said that fighter jets, attack helicopters and artillery targeted ISIS infrastructure and weapon sites. “All terrorists who are evil enough to attack Americans are hereby warned

Seven wild Asiatic elephants were killed and a calf was injured when a high-speed passenger train collided with a herd crossing the tracks in India’s northeastern state of Assam early yesterday, local authorities said. The train driver spotted the herd of about 100 elephants and used the emergency brakes, but the train still hit some of the animals, Indian Railways spokesman Kapinjal Kishore Sharma told reporters. Five train coaches and the engine derailed following the impact, but there were no human casualties, Sharma said. Veterinarians carried out autopsies on the dead elephants, which were to be buried later in the day. The accident site

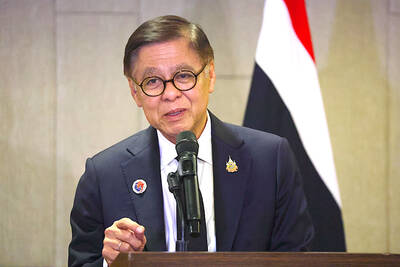

RUSHED: The US pushed for the October deal to be ready for a ceremony with Trump, but sometimes it takes time to create an agreement that can hold, a Thai official said Defense officials from Thailand and Cambodia are to meet tomorrow to discuss the possibility of resuming a ceasefire between the two countries, Thailand’s top diplomat said yesterday, as border fighting entered a third week. A ceasefire agreement in October was rushed to ensure it could be witnessed by US President Donald Trump and lacked sufficient details to ensure the deal to end the armed conflict would hold, Thai Minister of Foreign Affairs Sihasak Phuangketkeow said after an ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting in Kuala Lumpur. The two countries agreed to hold talks using their General Border Committee, an established bilateral mechanism, with Thailand

‘POLITICAL LOYALTY’: The move breaks with decades of precedent among US administrations, which have tended to leave career ambassadors in their posts US President Donald Trump’s administration has ordered dozens of US ambassadors to step down, people familiar with the matter said, a precedent-breaking recall that would leave embassies abroad without US Senate-confirmed leadership. The envoys, career diplomats who were almost all named to their jobs under former US president Joe Biden, were told over the phone in the past few days they needed to depart in the next few weeks, the people said. They would not be fired, but finding new roles would be a challenge given that many are far along in their careers and opportunities for senior diplomats can