Landslides and flash floods in Indonesia that killed as many as 180 people have set off a heated debate over the role logging may have played in the disaster that covered scores of homes in mud and rock.

Local environmentalists say logging in central Java worsened the situation and exposed the government's failure to rein in illegal logging rampant across the archipelago.

But the administration of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono denies that logging was to blame and has found unlikely support from international conservation groups. Yudhoyono said the best way to avoid future disasters was to move people from hilly areas or near fertile, flood plains.

They said the cause of the landslide likely had more to do with the makeup of central Java, where thousands live in flood-prone areas and farmers have torn down forests to clear agriculture land and plantations.

"Often the knee-jerk reaction to such tragic disasters is to blame them on excessive tree logging," said Greg Clough, a spokesman with The Center for International Forestry Research, a conservation group.

"Sure, deforestation may play a small part in flooding," he said. "But strong scientific evidence suggests even good forest cover will not prevent flooding in cases like Jember, where reportedly heavy rains fell for several days. Exceptionally long and heavy downfalls saturate the forest soil, making them unable to absorb more water.''

The landslides have reignited the logging issue and pushed it onto the front pages of local papers. The concern has also put the government on the defensive.

"There is no illegal logging case as reported by the media. The disaster is caused by the conversion of many forest areas to become coffee plantations," Forestry Minister Malam Kaban said while visiting Jember.

Forest Watch Indonesia and other environmentalists are not convinced and have called on the government to get tough on logging, especially illegal cutting that contributes to 90 percent of all timber.

Indonesia yesterday began enforcing its newly ratified penal code, replacing a Dutch-era criminal law that had governed the country for more than 80 years and marking a major shift in its legal landscape. Since proclaiming independence in 1945, the Southeast Asian country had continued to operate under a colonial framework widely criticized as outdated and misaligned with Indonesia’s social values. Efforts to revise the code stalled for decades as lawmakers debated how to balance human rights, religious norms and local traditions in the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation. The 345-page Indonesian Penal Code, known as the KUHP, was passed in 2022. It

‘DISRESPECTFUL’: Katie Miller, the wife of Trump’s most influential adviser, drew ire by posting an image of Greenland in the colors of the US flag, captioning it ‘SOON’ US President Donald Trump on Sunday doubled down on his claim that Greenland should become part of the US, despite calls by the Danish prime minister to stop “threatening” the territory. Washington’s military intervention in Venezuela has reignited fears for Greenland, which Trump has repeatedly said he wants to annex, given its strategic location in the arctic. While aboard Air Force One en route to Washington, Trump reiterated the goal. “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security, and Denmark is not going to be able to do it,” he said in response to a reporter’s question. “We’ll worry about Greenland in

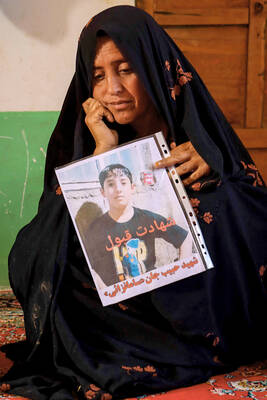

PERILOUS JOURNEY: Over just a matter of days last month, about 1,600 Afghans who were at risk of perishing due to the cold weather were rescued in the mountains Habibullah set off from his home in western Afghanistan determined to find work in Iran, only for the 15-year-old to freeze to death while walking across the mountainous frontier. “He was forced to go, to bring food for the family,” his mother, Mah Jan, said at her mud home in Ghunjan village. “We have no food to eat, we have no clothes to wear. The house in which I live has no electricity, no water. I have no proper window, nothing to burn for heating,” she added, clutching a photograph of her son. Habibullah was one of at least 18 migrants who died

Russia early yesterday bombarded Ukraine, killing two people in the Kyiv region, authorities said on the eve of a diplomatic summit in France. A nationwide siren was issued just after midnight, while Ukraine’s military said air defenses were operating in several places. In the capital, a private medical facility caught fire as a result of the Russian strikes, killing one person and wounding three others, the State Emergency Service of Kyiv said. It released images of rescuers removing people on stretchers from a gutted building. Another pre-dawn attack on the neighboring city of Fastiv killed one man in his 70s, Kyiv Governor Mykola