Steve Jordan, a self-published science fiction novelist, has to make lots of decisions. Although most of them have to do with plot points, narrative arcs and character development, Jordan has the added burden of deciding how to deliver the stories he creates to his online audience.

Some of those readers own dedicated devices like the Kindle, some plow through his books on smartphones, some use laptops and maybe even a few employ desktop PCs left over from the last century. (In true sci-fi fashion, Jordan doesn’t publish his novels on paper.)

The options are proliferating quickly for readers and the authors they love. While devices like the Kindle, the iPhone and the Sony Reader get much of the attention, practically any electronic device capable of displaying a few lines of text can be adapted as a reader. The result has been a glut of hardware, software and e-book file formats for readers to sift through in searching for the right combination.

“I’m already selling six different formats on my Web site,” Jordan said. “If they have a particular format they prefer, they can usually get it from me.”

The proliferation of formats has come about, in part, because most companies entering the e-book market have created a proprietary version.

This rugged individualism started falling out of favor several years ago, and today many companies have adopted the ePub format developed by the International Digital Publishing Forum, an industry consortium. Sony announced in August that it was switching to ePub as well.

“In the last two books I’ve put out,” Jordan said, ePub has been the most popular format.

Amazon.com, the dominant player in electronic books, still pushes its own format for the Kindle, its e-book reader. But it now also owns two companies — Mobipocket and Lexcycle — that sell e-books and reader software for smartphones.

Consumers may worry about issues like file compatibility, but publishers and software developers are more concerned over how to divide the proceeds of each sale. Jordan said he used to sell his books in the Kindle format but found the text conversion process onerous and Amazon’s high fees difficult to swallow. He now tells his fans who use the Kindle to buy Mobipocket editions, which can be displayed on that device, directly from his Web site.

The proliferation of formats has been a source of confusion and frustration for consumers, but it has been mitigated by the fact that consumers can load their smartphones and laptops with software for the various formats (which most of the major companies give away).

While a printed book has a fixed form, an e-book can change its spots. Even though most software packages offer similar interfaces, subtle differences exist, and many buyers choose a reader platform based on how they want a book to appear.

Neelan Choksi, one of the founders of Lexcycle, which developed the popular Stanza e-book reader for the iPhone and iPod Touch, said that was why he and his colleagues worked so hard to give users as many options as possible.

“All of the things that typesetters have done for a very long time,” Choksi said, “we mess up.” Customers can alter font styles, screen colors and a few other details, and they often have wildly different tastes.

The marketplace is also becoming more crowded as publishers sell stand-alone apps that display just one book. This simplifies the job for occasional e-book readers but doesn’t help those who want to build an extensive electronic library, but perhaps the ePub format will change that.

Hardware decisions can also be intensely personal. The Sony Reader and the Amazon Kindle, for example, employ power-saving LCD screens that help stretch out the time between battery charges.

But these dedicated readers compete with cell phones and computers that have brighter full-color displays illuminated by backlighting. The batteries may not last as long, but the screens can refresh much faster, allowing programmers to add animated visual gimmicks like simulated page-flipping.

Andrew Herdener, a spokesman for Amazon, said the company did not expect customers to do all of their reading on the Kindle.

“Our plan is to make the Kindle books available on many different devices and platforms,” he said. The company distributes a Kindle reader for the iPhone, for example.

Some companies are pursuing broader markets. Wattpad.com, which describes itself as a “community for publishing, reading and sharing” e-books, says its reader software works on hundreds of phone models. That has helped the company expand even in places like Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines, said Allen Lau, a co-founder of Wattpad.

“In those countries,” Lau said, “people are generally poorer and some of the operators don’t subsidize the phone. For them to spend a month or two of salaries to buy an iPhone, it doesn’t make sense.”

Wattpad allows e-books to be read on small, low-end phones that can display just a few lines of text at a time. Yet even in affluent tech-savvy countries like Japan, smaller devices are gaining in popularity because they are easier to carry around.

Lau said people were even writing entire novels on their cell phone, novels that might be 300 pages long as a paper book.

“I don’t know how they do it,” Lau said, “but they manage to do it.”

Writing the book itself is just the beginning. Nick Cave, a rock musician and sometime author, used an iPhone to write one chapter of his second novel, The Death of Bunny Munro. He and his longtime musical collaborator, Warren Ellis, then developed an original score for the book.

If more authors follow suit, readers will soon be fretting about the quality of their earphones, too.

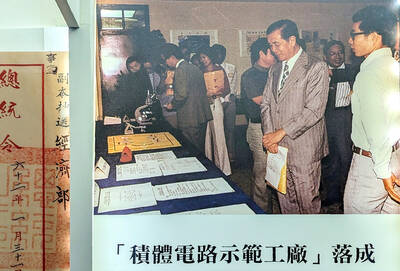

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

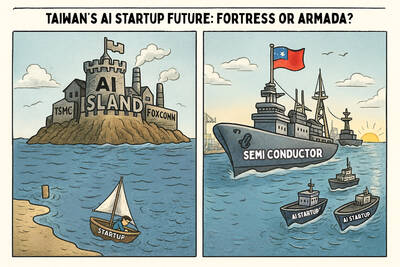

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage