Dec. 2 to Dec 8

In March 1980, almost everyone in Taiwan knew about the foreign “big beard” (大鬍子) whom the major newspapers just couldn’t stop talking about. He was allegedly involved somehow with a brutal incident that rocked society — the murders of former politician and activist Lin I-hsiung’s (林義雄) mother and twin daughters on Feb. 28, 1980.

This “big beard” was J. Bruce Jacobs, an American-born Australian academic who first came to Taiwan in 1965 as a postgraduate student, going on to become a renowned expert in Taiwan studies. After the murders, Jacobs was placed under police protection and barred from leaving the country for three months in an absurd debacle that he details in his his 2016 book, The Kaohsiung Incident in Taiwan and Memoirs of a Foreign Big Beard. The book is dedicated to the victims, with whom Jacobs was friendly with.

Photo: CNA

Jacobs was put on a government blacklist and couldn’t return to Taiwan until 1992; he made his final visit in November last year when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs awarded him with the Order of Brilliant Star with Grand Cordon for his contributions to democratization and human rights in Taiwan.

Jacobs died in Melbourne last Sunday at the age of 76. The Lin family murders remain unsolved.

FRIEND OF THE OPPOSITION

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

According to his book, Jacobs was interested in totalitarian regimes during college and planned to become a Soviet specialist. He signed up for an Oriental Civilizations class thinking, “I should know something about Asia and be done with it,” but soon became fascinated with China.

When he graduated in 1965, the Cultural Revolution had just begun and traveling to China was impossible. So like most academics interested in that country, Jacobs headed to Taiwan. He studied Chinese for a year in Taipei, and later returned to conduct a field study of local politics in rural Taiwan, where he grew used to “swearing rather automatically” in Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese) like the best of them.

As Jacobs rose up in the academic ladder, he kept returning to Taiwan. In 1979, he was hoping to meet with the newly appointed Government Information Office director-general James Soong (宋楚瑜). Soong was busy, and meanwhile he became friends with many dangwai (黨外, “outside the party”) politicians opposing the authoritarian Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), including Lin.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The dangwai politicians were angry at the government. While they were allowed to run in elections since 1969, the KMT suspended all electoral activities in 1978 in response to the US cutting relations with Taiwan. Lin was one of the core members of the dangwai magazine Formosa (美麗島), and the magazine’s headquarters were located above his home.

When Jacobs returned a year later, many of these friends, including Lin, were in jail over the Kaohsiung Incident, during which the military police clashed with democracy protesters during a rally organized by Formosa. He spent time with the families of the imprisoned, often visiting Lin’s house with other Dangwai members and playing with his daughters.

BANNED FROM TAIWAN

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

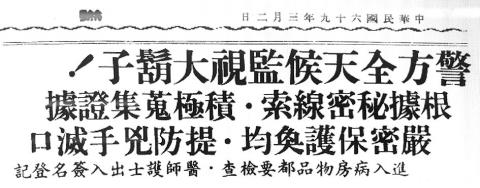

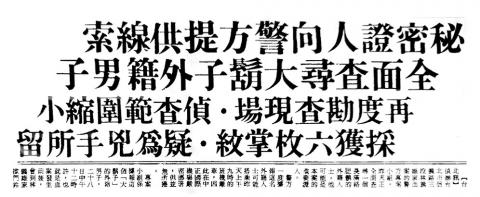

Jacobs found out about the murders that evening at the hospital where Lin’s wife and surviving daughter were staying. The next day, the United Daily News became the first outlet to call him “big beard” in the page 3 headline, “Secret witness gives police clue, full-scale search for big-bearded foreign male.” Jacobs writes that he had visited the Lin house the previous day around 6pm and nobody answered the door. The article claimed that he visited around noon, shortly before the murders happened.

The next day’s headline was “Police monitor big beard around the clock,” revealing that he had a PhD from Columbia University — essentially giving away his identity. Insisting that he had nothing to do with the murders, Jacobs agreed to be placed under 24-hour police protection. But the police continued to question him, the newspapers continued to update on the big beard’s alleged involvement, and he learned that he was barred from leaving Taiwan as an important witness to the case. He spent most of his time in a room in the Grand Hotel, or in court.

The bizarre and convoluted details of the next three months can be found in Jacobs’ book. Finally, on May 21, he was allowed to leave Taiwan after late national policy adviser Tao Pai-chuan (陶百川) brought the issue up to then-president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國). Once he was free from the grasp of Taiwan’s security agents, Jacobs “broke down and cried.”

Jacobs stayed away from Taiwan for the next 12 years. By 1992, he was teaching at Monash University in Australia and served as a member of the Australian-Chinese Council. Taiwan’s representative to Australia, Francias Lee (李宗儒), had been trying to get Jacobs to the country for years; he finally succeeded in securing a visa in June 1992 after telling the authorities Jacobs had become “too important to ignore.”

Taiwan was a very different place by then, and Jacobs noted the advances in democratization and the “surge of Taiwanese consciousness sweeping the island.” But the police were still following him around. This happened again during a visit in 1993, and his subsequent visa requests were often denied. After Jacobs brought up the issue when he met then-president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) in 1995, he was able to obtain visas with no issue. In 1996, Jacobs observed Taiwan’s first direct presidential elections.

However, Jacobs still noticed that he would be stuck at the immigration desk for at least half an hour every time he entered Taiwan. This continued until Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president in 2000 — he was pretty much free to come and go without hassle after that.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.