In A Bittersweet Dilemma (南丁格爾), a man is seen screaming angrily at a nurse who has just told him she can’t change his father’s diapers because there’s another patient who needs critical care.

“We are paying customers! My father is human too,” he exclaims when the nurse suggests that a family member perform the task. When her supervisor appears, however, the nurse is found to be at fault.

While this scene is a simulation, documentary director Tim Yang (楊朝鈞) has seen his fair share of similar incidents since his days as an intern. The neurosurgeon at Chang Gung Hospital took up the camera three years ago to examine why Taiwan has a relatively high nurse-to-patient ratio, but A Bittersweet Dilemma grew into a multi-angled exploration of why only about 60 percent of certified nurses still work in the field. Many leave within five or six years for completely unrelated professions, he says.

Photo courtesy of Tim Yang

“Nurses aren’t respected,” Yang says. “If they were, the system wouldn’t be like this. People wouldn’t treat them this way. They spend just as much time training as doctors. It’s just the job description that’s different.”

“Taiwanese nurses are like nameless housewives and mothers, silently helping doctors serve patients,” says Yang Wan-ping (楊婉萍), assistant professor of nursing at Fooyin University (輔英大學). “Over time, people start taking their care for granted. If a patient recovers, credit goes to the doctors, the patient’s constitution and devoted family members. People forget that nurses take care of many details and provide considerable professional assistance.”

On Thursday last week, the documentary won an award of excellence at the Labor Gold Awards (勞動金像獎), hosted by the Taipei City Government’s Department of Labor. It was screened at the Taiwan International Labor Film Festival last month and Yang is looking for more opportunities to bring attention to the issue.

Photo courtesy of Tim Yang

TREATED AS SERVANTS

During his medical internship, Yang wanted to do something about the hardships he saw in the nursing industry. He was a photography enthusiast in college, and after taking a few classes in documentary filmmaking during his time off, he launched A Bittersweet Dilemma as a one-person project.

At first, Yang thought that the problems simply stemmed from the nurse-to-patient ratios in Taiwan, which result in long work hours with little time to even eat or use the restroom. Regulations passed in May of last year require a ratio of at least 1:9 for medical centers, 1:12 for regional hospitals and 1:15 for district hospitals. By comparison, the maximum ratio allowed in California is 1:5 depending on the assigned unit, while in September, a Florida intensive care unit nurse spoke out against her hospital’s 1:8 ratio to the New York Times.

Photo courtesy of Tim Yang

“With every patient over four assigned to one nurse in a medical surgical unit, there’s an increase in mortality of 7 percent per patient,” the article states.

But when Yang started interviewing nurses, he discovered a different problem.

“Some told me that they didn’t mind taking care of many patients as long as the patients treated them with respect. I soon realized that I wanted to focus on the relationship between nurses and patients,” Yang says.

Photo courtesy of Labor Gold Award

“There has already been plenty of coverage about the problems with the law and the system.”

In a restaurant, for example, customers are happy to be there and willing to spend money. The staff is hired specifically to serve their needs. But that isn’t the case for hospitals, Yang says, which can often lead to the kinds of conflicts he portrays in the film. In addition to the simulated scenes, several professionals address the issue as well.

“People now tend to see nurses as service workers instead of medical professionals,” says Cheng Hui-ju (鄭慧如), a supervisor at Fooyin University Hospital. “They’re not patients, they’re customers, and they demand the best service, often treating nurses as mere maids.”

“Our jobs are hectic. We have to perform a lot of professional tasks such as transfusing blood and injecting antibiotics. Tasks such as pouring water and changing diapers really aren’t part of our job. But people often press the emergency buttons to ask us to do those tasks,” former hospital room nurse Huang Mei-ying (黃玫罃) says.

A LITTLE RESPECT

Yang didn’t have big plans for the film at first. But after he showed it to friends and family, they seemed to become more appreciative and less demanding toward the nurses. This prompted him to enlist a crew and turn it into a professional product.

“The first cut I did on my own was so awful,” he laughs. “I couldn’t even finish watching it.”

Yang says that although nurse training can take up to seven years, and they’re the ones who spend the most time with the patients and understand their needs the best, they often looked down on by doctors.

“There’s little collaboration between nurses and doctors,” Yang says. “They’re expected to simply take orders. Also, sometimes the patients refuse to listen to anything the nurses say, but once the doctors appear, they quiet down.”

Yang believes that the Florence Nightingale ideal of self-sacrifice for humanity is outdated.

“They have to consider their own well-being too,” he says. “The labor conditions have improved a lot already, but the fact is that the retention rate is still low. And instead of creating a more favorable environment, the industry prefers to offer more classes and train more nurses to replace those who leave.”

Despite the stark reality, Yang says many nurses remain afraid to speak out, and even his father, who is a hospital administrator, opposed him releasing A Bittersweet Dilemma, asking him why he would want to make his employers look bad.

“I’m not exaggerating anything, nor am I focusing on one hospital in particular,” Yang says. “This is what I want to do, so I released it anyway.”

Would the film, which is trying to help more nurses stay in the industry, scare off potential nurses by so directly presenting the horrors of the job?

“That’s why I included some encouraging parts in the end,” Yang says. “I know many nurses who sincerely enjoy taking care of patients. It’s the environment that’s the issue.”

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

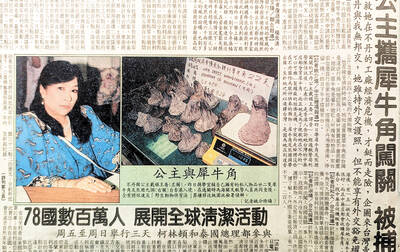

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized