Sept. 9 to Sept. 15

At 9am on Sept. 9, 1945, military representatives from the Empire of Japan and the Republic of China (ROC) assembled at the ROC Military Academy auditorium in Nanjing. During the 15-minute ceremony, the generals Yasuji Okamura and Ho Ying-chin (何應欽) signed the documents that marked Japan’s unconditional surrender to China after eight years of war.

But six people were missing from the ceremony: the delegation from Taiwan, which was technically still under Japanese control.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

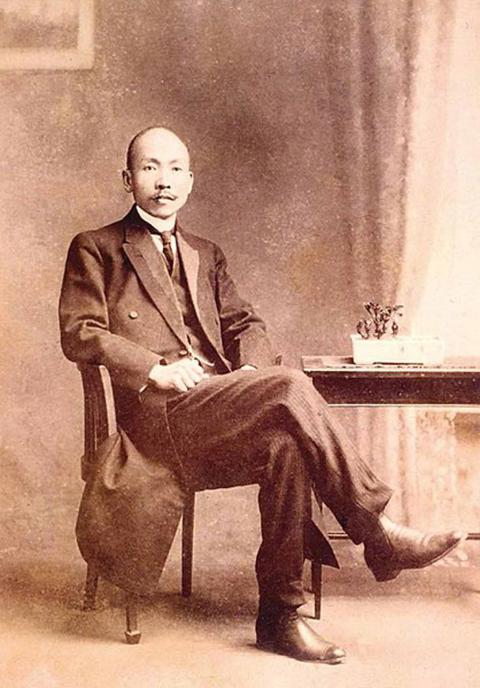

Led by Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂), head of the influential Wufeng Lin family (霧峰林家), the group of six Taiwanese intellectuals and social elites were already in Shanghai when they received the green light to attend the ceremony on Sept. 6.

However, the group was somehow “misled” by the Japanese and didn’t make it in time, according to a document held at Academia Historica (國史館). Kao Chen Shuang-shih (高陳雙適), daughter of delegation member Chen Hsin (陳炘) writes in her memoir that the Japanese officers who were in charge of their transportation stalled until they missed the ceremony, but she also mentions another version of the story where a Japanese official told the group the day before the ceremony not to attend.

The five were obviously dejected to miss such an important moment, as this was a time when Taiwanese were still excited to be rid of colonial rule and return to the “motherland” of China. The next day, Ho showed them the surrender documents, took them to the auditorium and described the ceremony.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

However, this optimism would not last long.

A REASSURING INVITATION

Japan surrendered to the Allies on Aug. 15, 1945, ending World War II. After an independence attempt that never materialized, the Taiwanese population anxiously awaited their fate.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

According to the book The Hundred Year Quest (百年追求), by historian Chen Tsui-lien (陳翠蓮), although most Taiwanese were happy to see the Japanese go and the war end, they were wary of celebrating. Nearly 200,000 Japanese troops were still stationed in Taiwan, and it was hard to tell if they were determined to resist to the end.

“Even if Taiwan was to fall under Chinese control, it was unclear when they would arrive and under what circumstances. Nobody could predict what the Chinese government would do with the Taiwanese either,” Chen writes.

Indeed, there was much animosity by Chinese toward Taiwanese as they supported the enemy during the war as Japanese citizens.

In this climate, Taiwanese leaders decided to send a group to China to connect with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). Led by Lin, they headed to Shanghai and met with local officials and Taiwanese expatriates, but on Sept. 6 they received a direct invitation to the surrender ceremony from KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) via Ho.

The formal invitation had a reassuring effect on the population. Chen writes that the KMT did so to show good will towards Taiwan and to indicate that they would be taking over the former Japanese colony soon.

Novelist Wu Cho-liu (吳濁流) writes in his autobiographical novel The Fig (無花果), “On Sept. 6, Lin Hsien-tang and five others who had long been resisting colonial rule, finally had their efforts recognized by the central government and received an invitation to attend the surrender ceremony in Nanjing. The news spread quickly, and it was as if Lin’s honor represented the honor of the 6 million Taiwanese. Everyone was beyond excited.”

Shih Yu-min (石裕民) writes in the study, “Chiang Wei-shui before and after the 228 Incident” (二二八事件前後的蔣渭水), “Wu’s description shows that the invitation by the KMT helped alleviate concerns about the identity of Taiwanese during the transition. People were assured that they were indeed Chinese, who belonged to the victorious side.”

Taiwanese civic leaders formed the Preparatory Committee to Welcome the Nationalist Government (歡迎國民政府籌備會), delivering ROC flags to schools and offices, hanging patriotic banners and teaching locals to speak Mandarin and sing the national anthem. They also threw a joyous extravaganza in Taipei to celebrate Double Ten National Day for the first time.

UTTER DISAPPOINTMENT

After his return, Lin whole-heartedly devoted himself to paving the road for the KMT’s arrival, while avoiding taking on a leadership position in deference to Chen Yi and the incoming government. He also started eagerly learning Mandarin — quite a contrast from when he often refused to speak Japanese during colonial rule.

On Oct. 24, Lin headed to the airport to welcome Chen Yi, and made the opening speech the next day during Japan’s surrender ceremony in Taipei. A month later, he officially became a KMT member and was later chosen as one of 18 Taiwanese members of the Taiwan Provincial Assembly.

However, Chen Yi did not trust him or other Taiwanese leaders, and the KMT turned out no better than the Japanese. Lin wrote in his diary about food shortages caused by rice being sent to China to support the fight against the Chinese Communist Party. He was also dismayed by the government’s centralized and authoritarian rule. He had fought for years under Japanese rule for Taiwanese autonomy, and the KMT shut down his proposal for provincial autonomy.

He soon realized that Taiwanese were still treated as second-class citizens and that nothing had changed, and in his diary he slammed the lack of public order, the gross misconduct of KMT soldiers as well as Chen Yi’s incompetence.

In 1946, Chen Yi started a witch hunt in Taiwan for hanjian (漢奸), or “Han Chinese traitors,” who worked for the Japanese to oppress Chinese. Chen Hsin, Lin’s fellow delegate to Nanjing, was arrested as a hanjian for his alleged involvement in the 1945 independence attempt, and was detained for a month before being deemed innocent.

The people’s frustrations boiled over in February 1947, culminating in the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was brutally suppressed. Chen Hsin, who was once so eager to welcome the KMT, was taken away by the police on March 11, never to be seen again.

Lin survived the incident and was even given a government position, but he had little authority. Utterly disillusioned, he tried to quit many times but his resignation was rejected each time.

Realizing that there was little place for him in Taiwan, Lin headed to Japan in September 23, 1949 under medical leave and refused all requests to return, dying in Tokyo in 1956.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South