Aug. 26 to Sept. 1

When Yang Chien-ho (楊千鶴) applied for a job at the Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) in the summer of 1941, she demanded the same salary as its Japanese employees. She had quit her previous job as a research assistant at Taihoku Imperial University (today’s National Taiwan University) after discovering that she made far less than her Japanese coworkers.

“The truth is that Taiwanese were suffering much greater injustices and oppression under the Japanese rulers, and some might say that I was being petty and short-sighted [for quitting] … But for me who had just entered the workforce, this was the first injustice that I encountered,” she recalls in her autobiography, The Prism of Life (人生的三菱鏡). “It makes me feel nostalgic to think of the resolve I had as an innocent young person who did not know how tough life could be.”

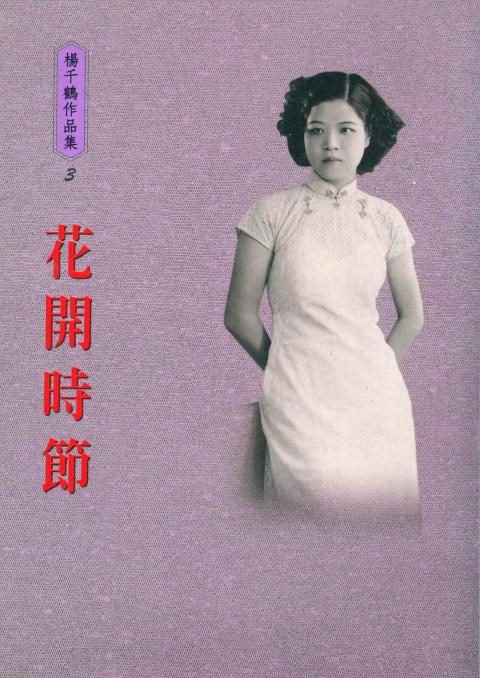

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Yang only accepted the job when arts and culture editor Mitsuru Nishikawa obliged.

It didn’t matter that she was only 19 years old and Taiwan had never seen a female reporter up to that point. Yang lived by her motto, “Our lives are short ... we must dream beautifully, live beautifully and die beautifully.”

Yang’s career as a journalist only lasted a year, and she stopped writing completely after the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) arrived in 1945 and banned the use of Japanese. However, she shone in other areas such as serving as one of the first directly-elected Taitung County commissioners in 1950. She picked up the pen again in 1989, and published her autobiography in 1993.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

A TAIWANESE VOICE

Yang was born in Taipei on Sept. 1, 1921. The Yang family had a tradition of giving away their daughters to other families to focus on raising sons, and such was the fate of her three elder sisters. But by the time her mother was pregnant with Yang, she was 42 years old and had much more say in the family. They let her keep the child and gave her every opportunity to succeed — she graduated from the nation’s top girls’ high school in 1940.

“What I really wanted to be was a lawyer,” she writes. “But that was a pipe dream in those days. If there is a next life, I want to be a lawyer who battles evil and seeks justice for the innocent and oppressed.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Nishikawa recalls that the paper’s new editor-in-chief instructed him to hire three female reporters — two Japanese and one Taiwanese — for the women’s section. The new boss wanted original content, finding the section “flavorless” as it only consisted of wire copy from Japanese agencies. Soon, Nishikawa’s childhood friend Yataro Miyata showed up at the newsroom with Yang, strongly recommending her for the job.

Nishikawa asked Yang to write something for his Literary Taiwan (文藝台灣) magazine. She leafed through a copy and noticed an article about a professional mourner — but she felt that the Japanese author seemed to be making fun of the practice, rather than trying to understand it. Yang recalled how hard she cried when her mother died, and wrote a personal essay on the topic as a rebuttal. Nishikawa liked it, and she got the job.

“I was determined to prove that a Taiwanese, who did not speak Japanese at home, could write articles just as competent,” she writes.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yang provided a distinctly Taiwanese voice to the paper, debuting with a piece on the nation’s signature cuisine of braised fatty pork (魯肉). Her most memorable interviews included acclaimed painter Kuo Hsueh-hu (郭雪湖) and Yang Chung-tso (楊仲佐), a well-known chrysanthemum breeder.

She also interviewed the “Father of Modern Taiwanese Literature” Lai Ho (賴和), a controversial figure who was jailed in 1923 for his pro-Taiwanese political activism. Nishikawa warned her that the piece might displease the authorities, but he still gave her the green light. Unfortunately, it was never published.

LIFE AFTER THE PAPER

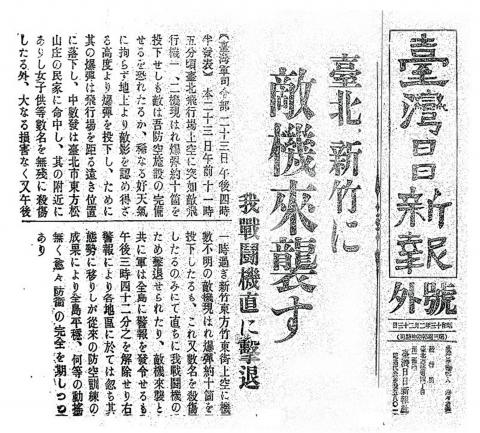

World War II intensified as Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, and the newspaper started focusing on war propaganda and promoting the Kominka Movement (皇民化運動), which sought to assimilate Taiwanese into Japanese culture.

When the newspaper decided to lay off two of the women’s section’s three female reporters, Yang was the first to volunteer.

“I was already disgusted by all the boring and dry Kominka articles … In addition, my family’s situation was such that I didn’t really need to worry about money,” she writes.

She continued to write for various literature publications, publishing her novel The Season When Flowers Bloom (花開時節) in the summer of 1942. The book depicted a group of high school girls on the cusp of graduation, exploring the conflict of being an educated, modern woman who is still expected to immediately get married out of school to a suitor chosen by her family.

One of the characters laments that women barely reach adulthood when they are rushed into marriage, then spend their whole lives raising children and serving others before they die.

“During this process [of a woman’s life], can she truly cast away her personal emotions and will, and allow fate to arrange her life however it sees fit?” she asks.

While Yang was able to marry a man of her choice in 1943, she still fell into the traditional roles of serving the family and raising children. She no longer wrote, but remained active as Taitung County Commissioner and served on the board of both of the Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association and the Taitung County Women’s Association.

In 1977, the family emigrated to the US, where Yang led a quiet life until her husband died in 1988. With her children all grown with families of their own, Yang picked up the pen again after more than 40 years, submitting a paper on Taiwanese literature between 1940 and 1943 for a conference in Japan. This opened the door to more than a decade of activity in the literary scene, keeping her busy until at least 2001.

Yang died in her home in Maryland in 2011. However brief, Yang recalls in her autobiography that her year as a reporter was one of the most memorable in her life.

“It was the most brilliant and glorious time for me, where sparks flew continuously day after day,” she writes.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

We have reached the point where, on any given day, it has become shocking if nothing shocking is happening in the news. This is especially true of Taiwan, which is in the crosshairs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), uniquely vulnerable to events happening in the US and Japan and where domestic politics has turned toxic and self-destructive. There are big forces at play far beyond our ability to control them. Feelings of helplessness are no joke and can lead to serious health issues. It should come as no surprise that a Strategic Market Research report is predicting a Compound