Aug. 11 to Aug. 17

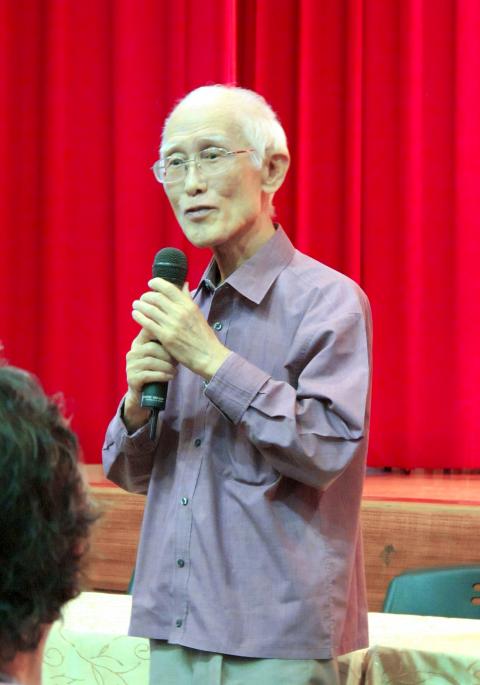

In August 1977, writers Peng Ke (彭歌) and Yu Kuang-chung (余光中) went on the offensive against nativist literature (鄉土文學), accusing the genre’s writers of harboring communist sentiments. This turned the debate political and pushed the nativist literature war toward its high point.

Nativist literature started gaining popularity in the early 1970s and referred to a genre that sought to realistically depict the lives and sentiments of ordinary people in Taiwan, reflecting their daily struggles as well as elements of local culture and society.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Peng, then-editor in chief for the state-run Central Daily News (中央日報), struck first in a lengthy article titled: “Without humanity, how can there be literature?” (不談人性, 何有文學?). He warns that focusing too much on social problems would foster class divisions and perpetrate hatred. He compares using social class to dictate literature to using social class as a political tool — clearly referring to the tenets of the hated communists in China.

Yu lays it out even more directly. In the first sentence of The wolf is coming (狼來了), he scathingly accuses nativist writers of promoting “worker-peasant-soldier arts and literature” (工農兵文學) championed by Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader Mao Zedong (毛澤東).

In the ensuing months, numerous articles and publications slamming nativist literature appeared, with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) even hosting a literary summit to address the issue. Curiously, it was the military who “ended” the war during the National Army Literary Arts Conference (國軍文藝大會) in January 1978.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

THE DEBATE BEGINS

There was little room for nativist literature in Taiwan before the 1970s. Starting in the 1950s, the ruling KMT exerted strict control over the literary scene, seeing it as another avenue to promote and maintain anti-communist sentiment. Taiwan-born writers also struggled because they were not familiar with the state-imposed Mandarin.

Under US influence, and also for anti-communist purposes, up-and-coming writers championed Western-style modernism during the late 1950s and well into the 1960s. Nativist literature publications, such as Taiwan Literary Arts (台灣文藝) founded by writer Wu Cho-liu (吳濁流) in 1964, started appearing in the mid-1960s. These works often focused on rural life, depicting realistically the modest lives of every day Taiwanese.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

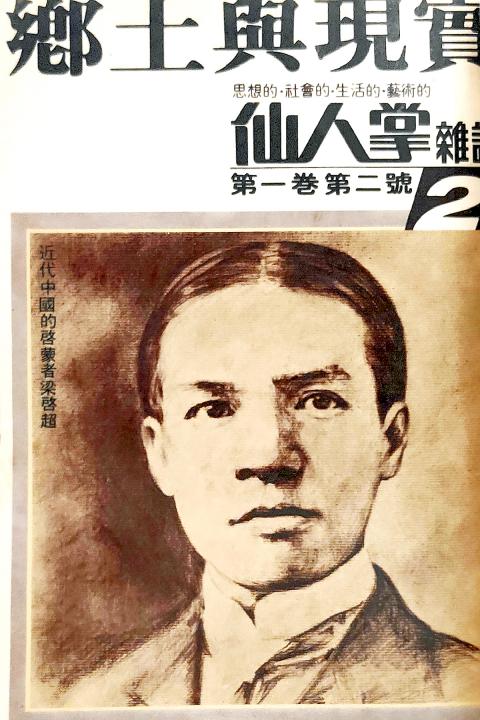

While the term had been gaining popularity throughout the 1970s, sources generally agree that the debate began with contrasting arguments that appeared in the second issue of Cactus Magazine (仙人掌雜誌) in April 1977. Author Wang Tuoh (王拓), who later became secretary-general of the Democractic Progressive Party (DPP), detailed the turbulent times in the early 1970s that led to the popularization of the genre: the explosion of patriotism and social awareness through the movement to protect the Diaoyutai Islands (釣魚台), the diplomatic disappointments of Taiwan leaving the UN and both the US and Japan getting chummy with China.

This led to a surge in nationalism, a shunning of American and Japanese imperialism and a growing interest in issues revolving around the everyday life of regular people. Wang wrote that nativist literature should examine social injustices and show support and empathy for the less fortunate.

“This literature should be rooted in the land and society and accurately reflect people’s lives and hopes. It shouldn’t just depict rural life, but also include everyday urbanites.”

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Wang concluded that a more apt name for nativist literature should be realist literature, one that would earnestly speak for the people and inspire the reader’s fervor for social change.

Yin Cheng-hsiung (銀正雄), on the other hand, disapproved of the negative tone that many nativist writers were taking, stating that the genre needed to return to its “pure” form instead of becoming a medium to transmit, as he saw it, hatred and anger.

Chu Hsi-ning (朱西寧) warned against nativist literature fostering regionalism since its central focus was Taiwan. From a Chinese-centric viewpoint, he questioned the “loyalty and purity” of Taiwan’s culture after half a century of Japanese occupation.

Several writers chimed in over the following months with differing viewpoints on whether writers should increasingly adopt Taiwan-centric voices or if doing so would lead to cultural divisions.

GOVERNMENT OFFENSIVE

After Peng and Yu’s articles were published, the KMT followed up by hosting the Second Literary Arts Summit (第二次文藝會談) on Aug. 29, 1977, with the goal of “deciding the future direction and mission of the literary arts.” Judging from the rhetoric, the aim was to put a stop to the rise of nativist literature and return to the anti-communist “combat literature” (戰鬥文學) of the 1950s.

Then-president Yen Chia-kan (嚴家淦) made the opening speech, with major politicians and military figures also speaking, showing how seriously the government took this issue. Yen stressed the importance of the literary arts as cultural warfare against the CCP, and sought to “curb the biased, decadent and abnormal leanings happening in the field today.”

In November, a military-run literary arts association published General Critique on Current Literary Problems (當前文學問題總批判), which included 76 essays by 40 prominent writers, all denouncing nativist literature.

However, the Jhongli Incident (中壢事件) broke out on Nov. 19, 1977, the first large-scale disturbance since 1947, as people took exception to purported KMT vote-rigging in local elections. Then-premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) was preparing to take over as president the following year, and the government understandably wanted this literature war to subside.

The rhetoric softened significantly during the National Army Literary Arts Conference in January 1978. Then-Political Warfare Bureau chief Wang Sheng (王昇) asked: “Should our literature not discuss the workers, peasants and soldiers? They contribute greatly to our society and should be celebrated, but we cannot take the same route as the communists.”

“The love of one’s native land is a natural feeling, and it can be expanded to the love of one’s country and the love of one’s people. This sentiment should not be suppressed … as long as the writers’ motives are pure, we should listen to them, understand them and work with them instead of branding them all as leftists.”

The “war” is considered to have ended at this point, but the discussion continued as Taiwanese consciousness continued to rise.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.