July 01 to July 07

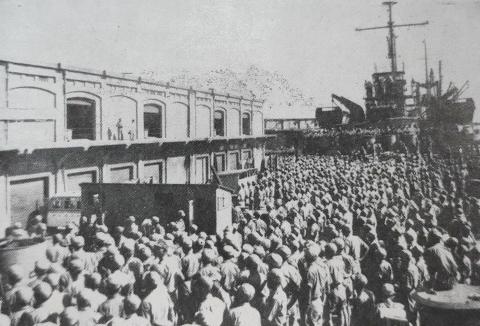

Even though General Huang Chieh (黃杰) described Phu Quoc island as a “paradise,” he and about 30,000 soldiers spent two years trying to leave — even staging a hunger strike at one point.

These Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) troops fled from China to French-ruled Vietnam in late 1949 and early 1950 after losing the Chinese Civil War, with promises from the French to escort them safely to Taiwan. But their hosts soon changed their minds and detained more than 30,000 soldiers and their dependents indefinitely under harsh conditions.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

As the war between the Viet Minh communists and the French intensified, the KMT troops were moved south to Phu Quoc, where they would later become known as the “Futai Brigade” (富台部隊).

When Huang first arrived in Vietnam on Dec. 13, 1949, he estimated they would be Taiwan-bound in a week. They did not arrive until July 2, 1953.

SCRAMBLE CROSS THE BORDER

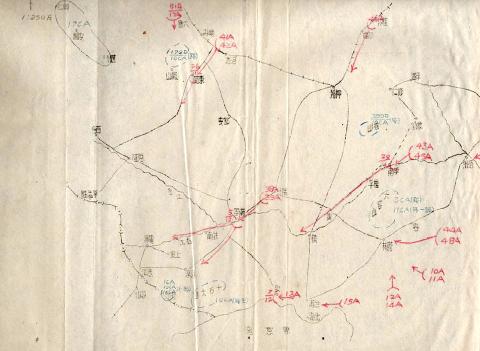

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

As the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) decimated the KMT armies and closed in on Huang’s troops near the Chinese-Vietnamese border in December 1949, Huang needed to retreat and regroup. The original plan was to enter Yunnan Province, but they soon received word that then-provincial governor Lu Han (盧漢) had switched allegiance to the Chinese Communist Party, allowing the PLA to overrun Yunnan. The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) had pretty much lost the war at that point, formally relocating its government seat to Taipei on Dec. 7.

As Huang ran out of options, he received a telegram from Chen Cheng (陳誠), who was serving as both provincial governor of Taiwan and chief of the Taipei-based Southeast Military and Political Executive Office (東南軍政長官公署). Chen suggested that Huang enter Vietnam and then decide whether to join him in Taiwan. Huang agreed, noting that this was the only way to preserve his forces.

At that point, Vietnam was still under control of France, which was allied with the KMT. Huang’s troops reached a town near the border on Dec. 11, while a KMT official negotiated the following terms with the French: the troops would divide into units of 500 and temporarily surrender their arms while the French would escort them to the port where they would head to Taiwan. The French would provide rations until they left the country, and open up an area for the 500 family members of the troops to stay for the time being.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Huang planned on waiting for official orders to cross the border, but fierce attacks from the PLA drove them to act early, departing in the morning of Dec. 13. As they moved closer to the border, Huang started feeling sentimental.

“The duty of a soldier is to defend every inch of our territory … My heart was full of shame and grief, and I felt boundless pain and loss. With each step, I kept looking back at the forests and mountains of [China], and I told my comrades, ‘I will definitely be back to reclaim [our lost territory]!”

With the PLA hot on their trail, the troops did not have time to adhere to the proper crossing procedures, moving hastily toward their temporary destination in Lang Son.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DETAINED INDEFINITELY

At the first meeting with the French in Hanoi, Huang noticed how the officials all avoided directly answering his inquiries. His premonition was right, as the French had changed their minds. The Chinese Communist Party had been pressuring the French, gathering 30,000 troops by the border, ready to invade any time. On Dec. 21, orders came from Paris to disarm the KMT troops and detain them within Vietnam to avoid becoming involved in the conflict — especially since they were still fighting the Viet Minh communists.

The troops were kept under harsh conditions in an abandoned mining district where they had to construct their own barracks using crude tools. With meager rations and lacking fresh water, many soldiers grew sick and died. Huang complained to the French officials, and the conditions were improved slightly. Huang reorganized the troops and tried to maintain morale while they waited.

As fighting between the Viet Minh and the French intensified in northern Vietnam, the KMT troops were gradually relocated south to Phu Quoc island off the coast of present-day Cambodia. There were about 8,000 residents on the sleepy island.

While scenic, the island had little infrastructure, and the troops built from scratch barracks, houses, docks, a hospital, school and other amenities. The Korean War was also raging on at this time, and the US hoped to re-arm the KMT troops so they could help resist the Vietnamese communists. The KMT in Taiwan also hoped that the troops could get involved, as it would earn them a shot at “retaking” China as part of a collective anti-communist effort.

Negotiations between the US and France dragged on with little progress, while the Taiwan side hoped to wait until the US lifted its blockade on the Taiwan Strait before making a final decision. The French, led by its Indochina commander Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, apparently had no intention of rearming the troops or letting them go to Taiwan; they hoped to keep them detained in order to negotiate with the Americans for more military aid. When the Americans realized this, they were adamant that the troops be sent to Taiwan.

On Christmas Day, 1951, the KMT troops couldn’t take it anymore, as three separate camps coordinated a hunger strike.

“I personally don’t approve of the hunger strike after all the hardships these troops have endured over the years ... but you should understand how much more painful it is to lose one’s freedom,” Huang writes.

After the death of de Lattre de Tassigny in January 1952, France and Taiwan finally agreed to send the troops to Taiwan, although it took another year of negotiations before both sides could agree on a solid plan.

“Usually one inevitably feels nostalgic when leaving a place they’ve stayed for a long time,” Huang writes. “But I was overjoyed to leave Phu Quoc, as it meant the end of our suffering. Ahead of us lies happiness and rebirth.”

Huang was the last one to leave Vietnam, attending an official banquet in Saigon (today’s Ho Chi Minh City) after the last ship departed Phu Quoc. After being toasted by KMT and French officials, Huang was so emotional he was at a loss for words, finally managing, “Thank you all for your help.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand