April 29 to May 5

The Duck King had only ruled for two months when the Qing Army stormed his court in today’s Tainan. They pursued him northward, and captured him with the help of locals. For a long time after, people recited a poem about the life of Chu Yi-kuei (朱一貴): “He wore a Ming Dynasty hat, but Qing Dynasty clothes. In May, his era name was Yonghe, in June he returned it to [emperor] Kangxi.”

A duck farmer from today’s Neimen District in Kaohsiung, Chu was an illegal immigrant who shared the same last name as the Ming Dynasty emperors. He claimed royalty and rose against a tyrannical local county magistrate, eventually capturing Tainan and proclaiming himself the ruler of the revived Ming Empire. The rebellion ultimately failed due to infighting and Qing reinforcements from China.

Photo: Su Fu-nan, Taipei Times

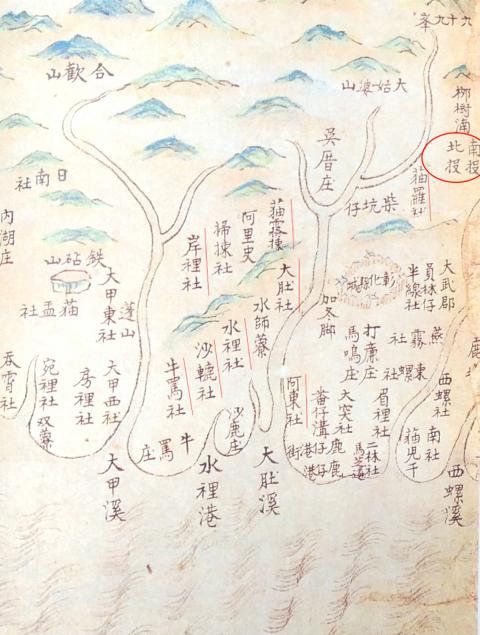

The Duck King’s uprising is well known as the earliest of the “three great uprisings” in Taiwan during Qing rule. But peace would not last long as Thao Aborigines clashed with Qing troops in 1725 after launching a series of attacks on Han Chinese encroaching on their land. In 1732, two other rebellions broke out, one led by the Aboriginal Taokas residents of Dajiasishe (大甲西社) and another by Chu’s former underling Wu Fu-sheng (吳福生). Wu took advantage of the Aboriginal unrest and ignited his own war in Fengshan (鳳山), also a district in Kaohsiung.

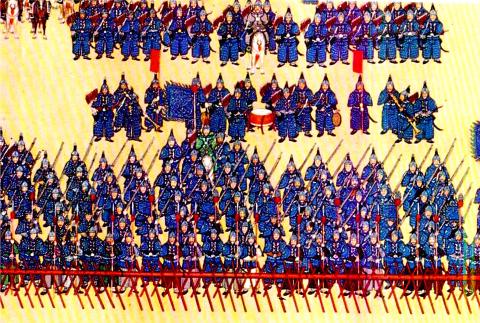

Like today, Taiwan’s residents did not exist in harmony, not even along racial lines. All three uprisings were put down with the aid of civilian militias — the Hakka Liudui (六堆) armies sent significant numbers to fight Chu and Wu, while the Pazeh Aborigines of Anlishe (岸裡社) and their Qing-friendly allies helped contain Chu’s forces and suppress the neighboring Dajiasishe rebels.

THE LOYALISTS

Photo: Huang Chia-lin, Taipei Times

One would have to be both courageous and desperate enough to cross the treacherous Taiwan Strait to begin a new life on a remote island that was believed to be full of bloodthirsty savages and deadly diseases. Violence seemed to be the norm once the Han Chinese settlers arrived. They fought among each other, seized land from Aborigines and frequently rose up against the Qing rulers, who saw Taiwan as an undeveloped backwater. They paid little attention to the island, leaving their local officials free to terrorize their constituents. A common saying during Qing-era Taiwan: “Minor unrest every three years, major unrest every five years.”

Shortly after the Duck King was executed in 1723, the Han Chinese population had increased so much that the Qing split massive Chuluo County (諸羅), which encompassed the northwestern two-thirds of Taiwan, into three to serve the settlers who continuously pushed northward. Soon they would reach the Dajia River (大甲溪),which was still largely Aboriginal territory.

Several local villages were loyal to the Qing: Anlishe helped quell a 1699 Aboriginal rebellion after being gifted with sugar, silver, tobacco and cloth. In 1715, along with several nearby villages, they swore allegiance to the Qing Emperor. They were rewarded again for preventing the Duck King’s armies from crossing the Dadu River (大肚溪).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In 1732, these villages came to the Qing army’s aid when Dajiasishe and more than 10 other villages rebelled. The Taokas leader was known by his Han Chinese name, Lin Wu-li (林武力), an indication that cultural assimilation was already strong.

The Qing officials had established an office in the area and were forcing the villagers into intermittent free labor while their soldiers harassed the populace. The rebel army swept south and besieged the county seat of Changhua, and soon almost all the Aborigines in the western part of today’s Taichung and Changhua counties had joined in.

The incident lasted almost a year, requiring the Qing to call for reinforcements from China. In the aftermath, the Qing gave all the villages Chinese names and built Zhenfan Pagoda (鎮番, suppressing the savages) on Bagua Mountain in Changhua. Anlishe became the dominant power in the area, but the Han Chinese settlers became so overwhelming that a large portion of these Aborigines migrated en masse in 1814 to Puli in today’s Nantou County, where their descendants still live today.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

THE HAKKA ‘YIMIN’

Wu Fu-sheng details his uprising in his confession to the Qing officials, where he says he took advantage of the Aboriginal rebellion to start his own. He and four friends became sworn brothers, with Wu claiming the title of grand marshal. They split into three divisions, with Wu’s bearing a white flag emblazoned with the words, “Victory for Great Ming” (大明得勝). With just 28 people, they struck on April 23, 1732, their ranks quickly swelling to over 300.

The Liudiu militia deployed about 10,000 strong to defend their territories and help the Qing, crushing the rebellion just a week after it started. Wu was caught a week later.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This militia was comprised of fighters from 13 large Hakka villages and 64 small ones east of the Gaoping River (高屏溪), stretching south from today’s Meinong (美濃) to the coast near Donggang (東港).

Hung Hsin-lan (洪馨蘭) writes in the study Rethinking the Boundary of the Liudui: An Anthropological Perspective (台灣南部六堆界限的再思考) that the militia first appeared during the Duck King rebellion, and was maintained for over a century as a mobilizable force due to continuous conflict with the surrounding Hoklo-speaking (also known as Taiwanese) people. It was not a regular force, as they had to elect a leader every time they took action and surrender their arms after returning home.

The Liudui were the first to be called yimin (義民, or righteous people) by the Qing, who built the Liudui Martyr’s Shine (六堆忠義祠) in today’s Chutian Township (竹田) to commemorate those who lost their life in battle.

Lee Wen-liang (李文良) writes in Discussion on Yimin after the Chu Yi-kuei Incident (清代台灣朱一貴事件後義民議敘) that yimin became increasingly important to the Qing since its forces in Taiwan remained about the same while the population exploded. Today, yimin temples can be found across Taiwan and the yimin worship ritual is still practiced by the Hakka.

The Liudui militia made its last stand at the Battle of the Burning Village (火燒庄戰役) against the Japanese troops who arrived in 1895 to take over Taiwan, which they received through the Treaty of Shimonoseki. The Japanese easily crushed the resistance and set fire to the entire Changhsing Village (長興村), and the Liudui yimin never fought as an organized unit again.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.