Twenty-six years after her best-selling novel Men Wanted (徵婚啟事) was published, author Jade Chen (陳玉慧) has made her debut as a film director with Looking for Kafka (愛上卡夫卡), which had its festival premiere at the 21st Shanghai International Film Festival in June last year and will be in theaters tomorrow.

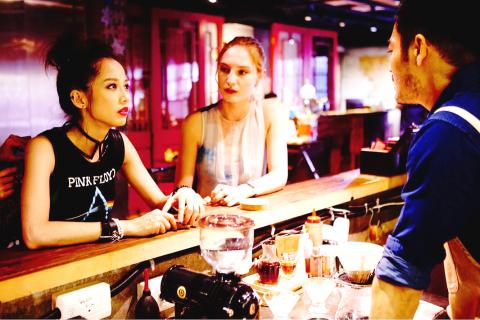

In the film, Pineapple (Jian Man-shu, 簡嫚書), an assistant at an avant-garde stage production of Franz Kafka’s novella Metamorphosis, finds herself in the uncomfortable position of having to help the girlfriend, Julie (Julia Roy), of the man she was unofficially dating, Lin Chia-sheng (Lin Che-hsi, 林哲熹), look for him after he goes missing. (Those familiar with Men Wanted or the impressive array of films, television shows, and stage productions it inspired will notice the striking recurrence of the missing love interest.)

The two women’s search for Lin, who has been cast as the unfortunate cockroach-man Gregor Samsa in the play, brings them on a tour through some of Taipei’s most popular tourist attractions and Taiwanese television’s most cliched elements, including an unplanned pregnancy, a dubious fortune-teller and a land dispute with a gang.

Photo courtesy of Flash Forward Entertainment

As they waltz by Ximending (西門町), Tianhou Temple (天后宮) and Raohe Street Night Market (饒河街觀光夜市), the Frenchness of Lin’s girlfriend Julie is contrasted with the wide-eyed Pineapple’s devotion to prayers and relative optimism — though they share a love for patterned headbands. Their personalities and cultures clash to provide comic relief to the prolonged absence of the male lead, who is meanwhile developing sympathy for one of his abductors, Chen Hung (Yuki Daki, 游大慶). I would not be the first to admit skepticism about having a foreign actor inserted into a local production, but Roy’s addition was not unnatural, owing in large part to her already strange predicament.

Beneath the commotion, it becomes tragically clear that Pineapple is unable to stay away from Lin, and, by extension, her romantic rival, Julie. Flashbacks of the former lovers, which parallel scenes of Lin and Julie in bed, consist mostly of them laughing, signaling the love she continues to feel for him. Pineapple asks fortune-tellers about Lin with increasingly less consideration for Julie, who is usually beside her though she does not know about their previous relationship. Her narration reveals a young love that is blind, forgiving and incessantly self-reflecting. If there really were a Heaven and a Hell, she would call there, too, looking for Lin, she says.

With the exception of isolated, heart-wrenching lines like these, Pineapple’s narration, which should have been a vehicle for the audience to enter her heartbreak, feels disconnected from her outwardly calm and collected response to being confronted with the presence of the woman she so envies. Her emotional development is also forced to compete with a number of distinctive psychologies that are at play: Lin’s resentment towards his father, Julie’s increasing frustration and Chen Hung’s moral dilemma of holding Lin captive for ransom to save his dying son — and that is to name just the most central characters.

With much more backstory to Looking for Kafka than a film can unpack in 93 minutes, a holding back plagues the fast-moving scenes. The self-sacrificing Pineapple hurts, but not enough to lose her composure in public or in private. A crueler Lin would have helped the audience feel a stronger sympathy and connection towards Pineapple, but that was not the case. Julie should be more shaken by her situation, but instead she takes it — and her pregnancy — too well to be persuasive.

Moments in the film also threaten to break the cinematic illusion, such as when Lin willingly walks towards a group of hostile-looking men standing next to a van or when the police officers fail to notice Chen Hung fleeing the scene in a truck after Lin tosses him the ransom. To be fair, the film is billed as a romantic comedy. Yet the delivery of the comedic scenes lacks the unapologetic precision it needs.

In Looking for Kafka, many thoughts run through the minds of the characters, but aren’t given ample time to be communicated, whether via words, action or body language. The film struggles to align the characters’ inner worlds with what is going on on-screen while also moving an ambitious plot forward. A few quiet scenes give the audience the dose of intimacy it craves, but, for the most part, there is little time for the characters or the audience to slow down and absorb the emotions.

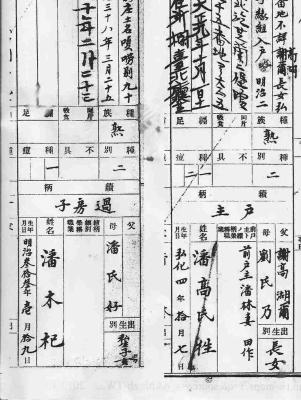

Feb. 9 to Feb.15 Growing up in the 1980s, Pan Wen-li (潘文立) was repeatedly told in elementary school that his family could not have originated in Taipei. At the time, there was a lack of understanding of Pingpu (plains Indigenous) peoples, who had mostly assimilated to Han-Taiwanese society and had no official recognition. Students were required to list their ancestral homes then, and when Pan wrote “Taipei,” his teacher rejected it as impossible. His father, an elder of the Ketagalan-founded Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會), insisted that their family had always lived in the area. But under postwar

In 2012, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) heroically seized residences belonging to the family of former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), “purchased with the proceeds of alleged bribes,” the DOJ announcement said. “Alleged” was enough. Strangely, the DOJ remains unmoved by the any of the extensive illegality of the two Leninist authoritarian parties that held power in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. If only Chen had run a one-party state that imprisoned, tortured and murdered its opponents, his property would have been completely safe from DOJ action. I must also note two things in the interests of completeness.

Taiwan is especially vulnerable to climate change. The surrounding seas are rising at twice the global rate, extreme heat is becoming a serious problem in the country’s cities, and typhoons are growing less frequent (resulting in droughts) but more destructive. Yet young Taiwanese, according to interviewees who often discuss such issues with this demographic, seldom show signs of climate anxiety, despite their teachers being convinced that humanity has a great deal to worry about. Climate anxiety or eco-anxiety isn’t a psychological disorder recognized by diagnostic manuals, but that doesn’t make it any less real to those who have a chronic and

When Bilahari Kausikan defines Singapore as a small country “whose ability to influence events outside its borders is always limited but never completely non-existent,” we wish we could say the same about Taiwan. In a little book called The Myth of the Asian Century, he demolishes a number of preconceived ideas that shackle Taiwan’s self-confidence in its own agency. Kausikan worked for almost 40 years at Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reaching the position of permanent secretary: saying that he knows what he is talking about is an understatement. He was in charge of foreign affairs in a pivotal place in