“Having come all this way, I’d rather pay to get in, and really learn something about the way people lived back then.”

So said Vincent Mattsson, a Swedish tourist I met outside the Lu Jing-tang Residence (盧經堂厝) in Tainan City’s Anping District (安平). Of the 10 days he was staying in Taiwan, he planned to devote two to places of historic and cultural importance in Tainan.

There is no admission charge at the Lu Jing-tang Residence, and after twice looking around this single-story building — completed circa 1902 and opened to the public in 2014 — I could see what Mattson was driving at.

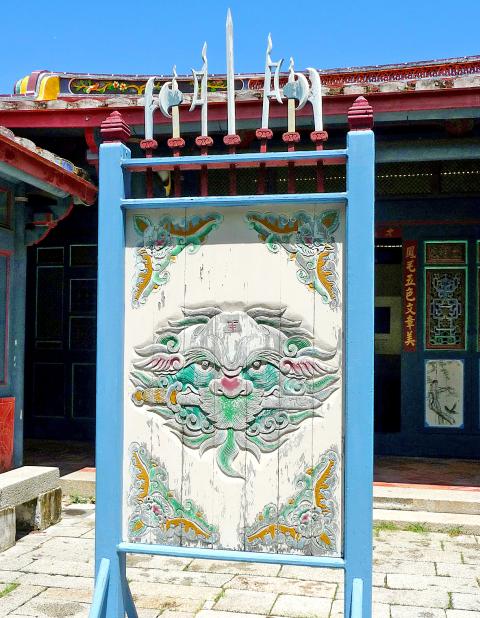

Photo: Steven Crook

A trilingual information panel out front informs visitors that Lu Jing-tang (盧經堂) dealt in sugar and kerosene, owned warehouses nearby and that this residence-cum-office faced the harbor. (Due to land reclamation, the nearest wharf is now 300m away.)

“Which room was his office?” Mattson asked me. “It would be nice to know the function of each part of the building, but half of it’s a shop.”

He was referring to an outlet of Dagang Herb Dream House (大港香草夢工坊), which sells handmade lotions and insect repellents. The business is being incubated by Dagang Community Development Association in Dagang Li (大港里), a mere 3km inland from Anping. When I told him later via e-mail that it was an ultra-local social enterprise, he responded: “Better than renting the space to a multinational corporation, of course.”

Photo: Steven Crook

The next line of Mattson’s e-mail caught me by surprise. “Since getting home, I’ve been thinking about the toilet there.”

There was nothing wrong with the purpose-built toilet block next to the residence, he wrote. Instead, he was wondering where the building’s inhabitants had washed themselves, there being no obvious bathroom in the original structure. “Did they go down to the harbor… That’s what I mean about understanding lifestyles long ago. Is no one else curious?”

People who do not live in Tainan have to pay NT$50 to enter Fort Zeelandia (安平古堡), the main Dutch base in the mid-17th century. For their money, tourists do get a pretty good museum. It covers, among other things, aspects of the fort’s construction, items of pottery uncovered by archaeologists and the fate of Frederick Coyett, the governor who surrendered the fort to Koxinga in 1662.

Photo: Steven Crook

Nonetheless, some foreign visitors have come away feeling a little disappointed by the lack of information available at the fort. Michael Booth, author of The Meaning of Rice, went there earlier this year for a book about East Asia he is writing.

“As I’ve been researching the history of Taiwan, it occurs to me that places like the fort are of incredible historic value, not just for Taiwan, but for the world’s heritage,” the British travel/food writer told me via e-mail. “Their history is the history of colonialism and global trade in East Asia which is the history of China, of Korea, of Japan and directly connects with what is happening in the region today. I really enjoyed the festive atmosphere at Anping when I visited, but was a little in the dark regarding the site’s history. I think the two can live together, it’s just a question of good curating and management.”

Hoping to get an official perspective on the issue of “free entry to a commercialized space” versus “historical authenticity at a price” I contacted Tainan City Government Cultural Affairs Bureau. The bureau not only manages the Lu Jing-tang Residence and more than a dozen other relics around the city, but also funded the renovation effort earlier this decade that transformed the residence from a near-ruin to a highly photogenic landmark.

Photo: Steven Crook

I wanted to know if budgetary pressure is a decisive factor. Having learned from Chinese-language blogs that there used to be a NT$50 admission fee for the Lu Jing-tang Residence, I wondered if the bureau had found that people are unwilling to pay to see such places. Without rental income from souvenir stores and coffee-shops, perhaps some of these buildings cannot be maintained and kept open.

The bureau never responded, but I made return visits to other Anping attractions that now cost nothing to enter.

Taiwan’s defunct salt industry intrigues quite a few Western visitors, but they will not learn much about it at Sio House (夕遊出張所), 500m west of Fort Zeelandia.

Photo: Steven Crook

The 96-year-old single-story timber building was originally a workplace for clerks assigned to the Monopoly Bureau of the Governor-General of Taiwan, a branch of the Japanese colonial authorities that controlled trade in alcohol, tobacco, camphor, matches, opium and petroleum, as well as salt. After World War II, it became a staff dormitory for salt-industry administrators — and that is about all that can be learned on-site.

The interior is organized with one end in mind: The sale of salt and salt-themed gifts. Dishes of colored salt, one for each day of the year, catch the visitor’s eye, and staff explain how the color reflects the personality of those born on that day. It would be quite easy to come here and never notice the replica-in-salt of the National Palace Museum’s Jadeite Cabbage. Massively larger than the original, it is remarkable in its own way, and deserves a much more obvious location.

Haishan Hall (海山館) is far older, dating from just after Taiwan’s annexation into the Qing Empire, and has not been commercialized in the same way as Sio House. It is more of an art gallery than anything else, yet some inexpensive and unrelated gewgaws are offered for sale.

Photo: Steven Crook

My half-empty glass view is that Taiwan does not lack for places to shop or drink coffee, and that historic sites which have survived into the 21st century should be, above all, places of enlightenment and beauty.

At the same time, I acknowledge that the desire to preserve tangible antiquity in Taiwan is stronger than ever before. In the early 1990s, I noticed several derelict yet impressive buildings, and assumed they would eventually be replaced with something more useful but less alluring. I am glad my pessimism was proved wrong in the cases of Tainan’s Hayashi Department Store (林百貨) and Xinhua Butokuden (新化武德殿). Filling the former with shops is in keeping with its history, obviously. The latter is once again a place where youngsters practice martial arts — which just goes to show that rescuing an old building need not involve selling its soul.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. Having recently co-authored A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, he is now updating Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful