July 30 to Aug. 5

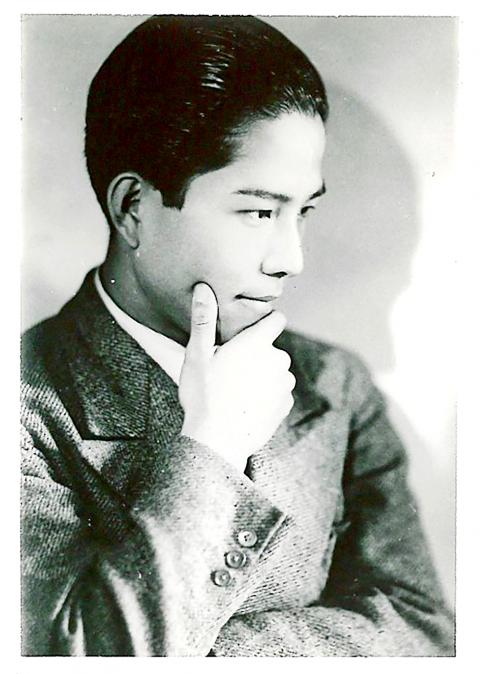

Despite his talent and accomplishments, composer Chiang Wen-ye (江文也) was a victim of circumstance throughout his life.

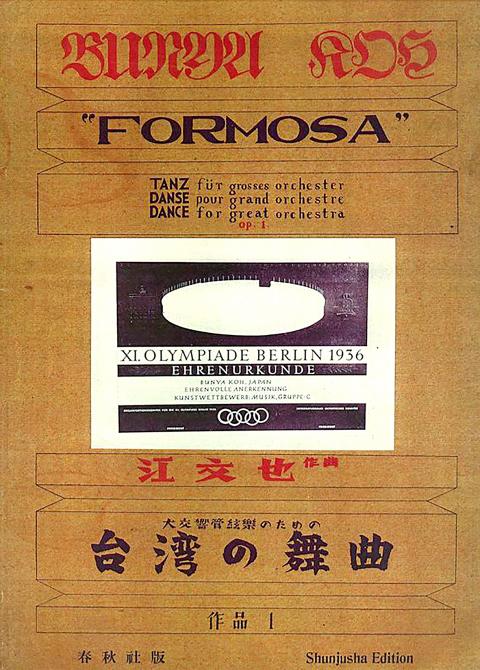

The Japanese tried to downplay his win in the 1936 Summer Olympics for Japan — Chiang, who didn’t attend the games, did not know he had won an honorable mention for his orchestral work, Formosan Dance (台灣舞曲), until a package arrived at his home nearly a month after the games concluded.

Taipei Times file photo

According to a Chiang biography by Liu Mei-lian (劉美蓮), Saburo Moroi, the only musical contestant from Japan to attend the games, failed to report Chiang’s honor when he returned home.

This was supposed to be huge news. The arts competition in the Olympics had only been around since 1912, and Chiang, along with two Japanese painters, became the first ever Asian winners that year. The next two Olympics were canceled due to World War II, and the arts competition was canceled after the 1948 games — making Chiang the only Asian to win a music medal in Olympic history.

However, the Japanese probably didn’t like the fact that the 26-year-old Chiang took the glory, while Moroi and three other experienced Japanese contestants, came up empty-handed. Chiang was young, had been learning composition for only a few years and, crucially, he wasn’t Japanese.

Photo courtesy of Liu Mei-lian

DECLARATION OF WAR

In fact, Chiang had to personally take the medal and certificate to the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun newspaper to get the word out. Other newspapers had no choice but to follow suit after seeing the report, Liu writes.

Moroi continued to publicly belittle Chiang, stating that Formosan Dance received attention solely due to its novelty factor to the Western judges as a fusion piece with strong Taiwanese and Asian elements.

Taipei Times file photo

“I believe that if we want to compete against Western pieces, we need to create works that are completely rooted in Eastern music,” Chiang told the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun. “Today’s Japanese composers are bound by their pride and ego, and aside from a few progressive ones, they find it hard to free themselves from Western theory. I have no formal musical education, so this is the only idea I can offer.”

Nevertheless, music publishers released Formosan Dance as both piano and orchestral scores, a feat that Chiang was immensely proud of, as the piece was essentially a reworking of his first composition. And in his native Taiwan, this was front page news.

“Byron once said, ‘I woke up one day and found myself famous,’” Chiang wrote in his diary, which for him summed up the year 1936.

Photo: Liu Wan-chun, Taipei Times

“I know how that feels now. My blood is boiling, my body is jumping, my life is colorful,” he wrote.

However, he was obviously stung by the Japanese critics.

“My work does have some fantastical elements in it, and this has led them to feel that it’s merely a frivolous exotic novelty and has no value. They want to ignore my existence … but this is my declaration of war to the musical world. I will continue to put myself at the perilous frontlines, but it seems that nobody treats me as a worthy opponent, only chattering about my work like a sparrow.”

SINGER TO COMPOSER

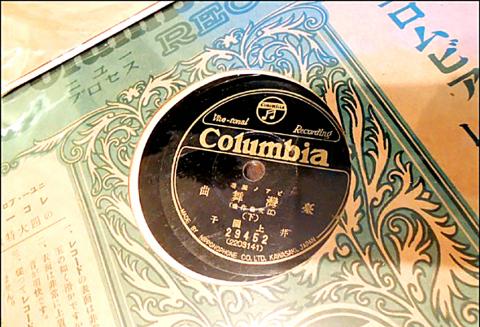

Born in 1910 in Taipei’s Dadaocheng area, Chiang actually never spent much time in Taiwan. His family moved to China’s Xiamen when he was four years old, and in 1922 he headed to Japan to study. During high school, he spent a summer interning at a power plant in Taipei. Upon college graduation, the aspiring singer auditioned for Columbia Records (the Japanese version) and released his first single, The Three Human Bomb Heroes, which commemorated three Japanese soldiers who sacrificed their lives during the invasion of Shanghai.

In April 1934, a successful Chiang headed to Taiwan for a concert tour. Lin writes that this may have been the first time a Taiwanese vocalist toured Taiwan, as previous island-wide concerts only featured Japanese singers. It was this visit that provided Chiang with the inspiration for his first composition, Nights in the City, featuring Dadaocheng, Wanhua and the center of old Taihoku around the Governor-General’s office. His desire to write about his homeland was bolstered by another tour that August with Taiwanese musicians living in Japan.

During the post-Olympics interview with the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, Chiang said: “I accidentally became a singer, but I quickly found that it was not satisfying enough for me just to sing. So I started learning composition on my own.”

Chiang continued to rack up the accolades in various competitions, and composed countless pieces, many featuring Taiwan including his four songs on Aborigines, which he referred to as “raw savages” (生蕃). In 1937, he reportedly composed the melody for the anthem of Beijing-based Provisional Government of the Republic of China, which is mostly seen today as a Japanese puppet state.

Soon, Chiang would accept a teaching job at Beijing Normal University. He split his time between Beijing and Japan, with these years being his most prolific as a composer.

DARK TIMES

When Japan surrendered in August 1945, many Taiwanese living in China were targeted by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) as former Japanese citizens. Chiang was undaunted, and even presented his latest work to the KMT, only to be arrested as a hanjian (漢奸, traitor to Han Chinese) due to his previous pro-Japanese work, which included the theme for a film about Japanese troops ravaging China.

“I forgot that life also has a side that’s dark and hypocritical,” he wrote in his diary in jail.

But this was only the beginning of the darkness. He stayed in China when the KMT retreated to Taiwan in 1949, continuing to teach and compose. But in 1957, Chiang became a prime target in the Anti-Rightist Movement which mostly targeted intellectuals. Chiang lost his job and was forced to sell his Steinway piano to make ends meet, but he continued to write music.

The final blow came in 1966, when the Cultural Revolution was in full swing. Chiang was again targeted, and ended up working as a janitor with his records, books, scores and manuscripts confiscated. He was eventually sent to a labor camp. Although he was rehabilitated and given back his professorship in 1978, Chiang’s body had suffered from years of hardship, and his glory days mostly forgotten.

Around 1980, several overseas Taiwanese musicians “rediscovered” Chiang. One of them was Chang Yi-jen (張已任), who was staying at the house of Chiang’s mentor, Russian-American composer Alexander Tcherepnin. While leafing through Tcherepnin’s collection, one composer named Bunya Koh (Chiang’s Japanese name) stood out. Chang asked Tcherepnin’s wife about the name.

“He’s Taiwanese like you,” she said.

Chang’s article on Chiang appeared in the China Times (中國時報) in 1981, and by a lucky coincidence two other Taiwanese who were researching Chiang published articles during the same month. Chiang was once again the talk of the town. But by that time he had already suffered several strokes and was a bedridden old man.

He died two years later in Beijing.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)