On May 23, 1895, the Taiwanese declared independence through the Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Formosa. A few weeks earlier, on April 17 1895, the Qing Dynasty government in Beijing, represented by viceroy Li Hongzhang (李鴻章), had signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki, and under the provisions of the treaty, Taiwan had been ceded to Japan in perpetuity.

The treaty came as a total surprise to the Taiwanese. Neither the population nor officials had been consulted. In 1887, Taiwan had gained more prominence when it was officially declared a province of the Qing Dynasty; infrastructure had been built, the economy had grown and a relatively free and open society had developed.

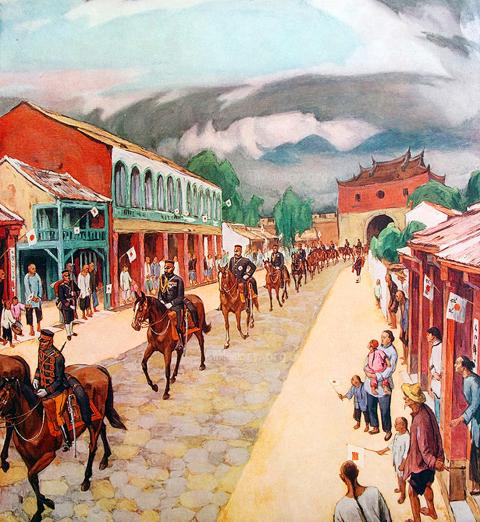

REPUBLIC OF FORMOSA

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Under governor Liu Ming-chuan (劉銘傳, 1887-1891), Taiwan attracted intelligentsia and literati from China, escaping Beijing’s oppressive atmosphere under late Qing rule. The mix of these intellectuals and local gentry brought about a flourishing of art, literature and politics in Taiwan (see “When Taiwan was China’s (for seven years),” Feb. 27 edition of the Taipei Times).

The local gentry abhorred the impending takeover by a new foreign ruler, and convinced Governor Tang Ching-sung (唐景崧) to declare a Republic of Formosa, the first independent republic in Asia, which he led as president. A new government was inaugurated on May 25, 1895.

The Republic of Formosa was quite a progressive enterprise. It had officials “elected by the people of Taiwan,” and a parliament made up of local gentry. It had its own flag — the now-famous yellow tiger flag — issued paper money and postage stamps (today some of the most valuable in the world) and had a functioning cabinet.

The foreign minister in the new government was Chen Chi-tung (陳季同), an experienced diplomat in the Qing government, who spoke French fluently. Chen had lived in Paris for many years and had even written a book, Les Chinois peints par eux memes (The Chinese painted by themselves), explaining “China” to the French public.

His experience in France had exposed him to the workings and symbolisms of the-then young French Republic, and he was the one who designed much of the republican symbols for the new Republic of Formosa.

Another cabinet member was “Black Flag” general Liu Yung-fu (劉永福), who had fought together with Governor Tang against the French in Indo-China, and who had been asked to come to Formosa to help defend it against the incoming Japanese. He commanded an army of some 100,000 Qing government soldiers.

Another military leader was Chiu Feng-chia (丘逢甲), a local Hakka warlord, poet and scholar who had become vice president and headed the gentry in what is today’s Changhua County. Chiu had entered the civil service when Tang was governor, and was one of the most prominent advocates of self-rule, self-determination and independence. He also commanded a local militia of some 50,000 well-trained fighters, who would put up the biggest fight against the incoming Japanese.

Six days after the declaration of the Republic of Formosa, Japanese troops under general Kawamura Kageaki landed near Keelung and started to move south. The Qing soldiers and the local militia in the north were no match for the well-armed and trained Japanese: on June 5, 1895 President Tang fled via Tamsui, and on June 7 1895 the Japanese army entered Taipei.

During the next five months, the Japanese pushed further south. Conquering Taipei had been relatively easy: The Qing soldiers had no real familiarity with the territory, gave up easily and fled without much of a fight. But in central Taiwan, the local militia were strongly attached to “their” territory and put up stiff resistance. In the Battle of Baguashan (八卦山戰役), which took place on Aug. 27, 1895 near Changhua, the Taiwanese militia almost brought the Japanese advance to a halt.

However, because of their overwhelming manpower and gunfire, the Japanese were able to keep going, and by early October Japanese troops were approaching the gates of Tainan, the stronghold of the remaining Republic of Formosa under Black Flag Liu and militia leader Chiu Feng-chia.

Black Flag Liu decided to flee: on Oct. 19, dressed as a coolie he made it to Tainan’s Anping District (安平) with some 100 officers. He boarded the British ship Thales, which sailed the next morning. It was pursued by the Japanese cruiser Yaeyama, which stopped and searched the Thales in the middle of the Taiwan Strait, but Liu had disguised himself well and was not found.

Local merchants in Tainan as well as the small European community worried about the fierce fighting that would inevitably reach the city. They convinced the disillusioned Qing troops and militia to lay down their arms, and then sent a delegation of two Presbyterian missionaries, James Fergusson and Thomas Barclay, to the Japanese camp of general Nogi Maresuke with the message that Tainan was surrendering peacefully.

After the fall of Tainan, the Japanese declared that Taiwan had been pacified, but for some 20 more years — until around 1915 — they would have to resort to major military campaigns to subdue the many uprisings on the island.

SIGNIFICANCE FOR TODAY

The short-lived Republic of Formosa was in a sense way ahead of its time. It tried to lay the foundation for the idea that Asians were ready for progressive rule, based on the democratic concepts which had their basis in the American and French republics. It did show the deep-seated desire of the educated and literate part of the population for representative government.

Additionally, the invasion by a common enemy — the Japanese — became a very formative period in Taiwan’s history and helped shape a Taiwanese identity, as it forced the very disparate population groups (Hoklo-speakers, Hakka and Aborigines) that had until then competed with each other for land and other resources, to work together to fend off the incoming invaders.

The hasty decisions by the leadership in Taipei in May 1895 were made in reaction to the decision at Shimonoseki in April 1895: they wanted to forestall a Japanese takeover. However, they insufficiently considered the lack of military power available for the defense of the island. This proved to be a main factor in its failure.

The second factor was the lack of international allies who would be able to generate sufficient political, diplomatic and military weight to counterbalance the invading force. Foreign Minister Chen had extensive contacts with the French, but they were too far away, and could not mobilize a sufficient force within the required time.

Thus, the Republic of Formosa’s chapter in Taiwan’s history carries important lessons for Taiwan today: Ensure that the country has adequate military capabilities to defend itself, build a solid network of significant allies who can be counted on and who have the capabilities and the political will to come to the country’s defense.

Gerrit van der Wees is a former Dutch diplomat. From 1980 through 2016 he served as the editor of Taiwan Communique. He teaches History of Taiwan at George Mason University.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)