March 19 to March 25

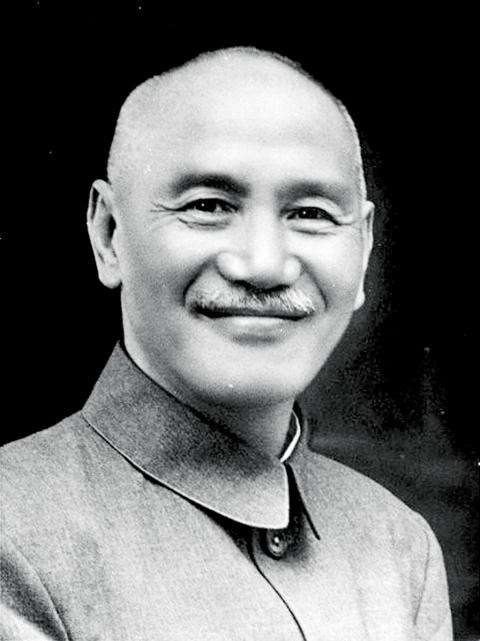

While Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) ran unopposed for his last three presidential elections in 1960, 1966 and 1972, he actually had a challenger in his first election in Taiwan.

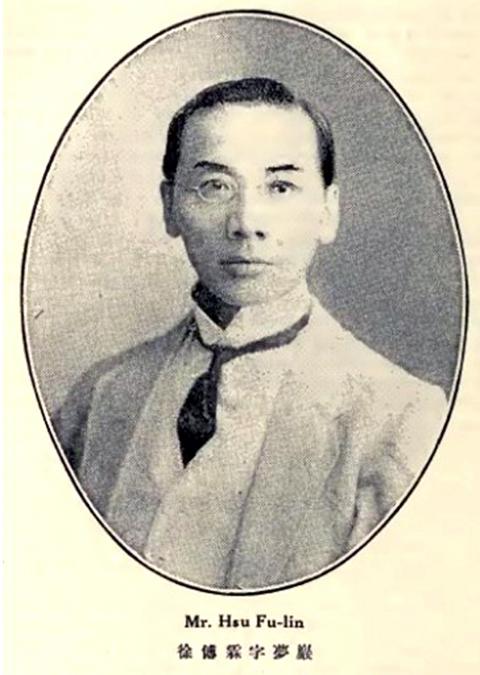

On March 22, 1954, 75-year-old Hsu Fu-lin (徐傅霖) of the China Democratic Socialist Party (中國民主社會黨) became the last person to challenge a Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) presidential candidate for the next four decades. Chiang’s successors, his son Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) and later Lee Teng-hui (李登輝), continued the practice of running uncontested.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Taiwan did not have direct presidential elections back then; the nation’s leader was chosen every six years by the National Assembly. The problem was that this assembly’s members were supposed to be elected directly by the people — but elections had been suspended since 1947 and the same members would remain in place until 1991.

On that day, 1,573 National Assembly members gathered at Taipei’s Zhongshan Hall. It was a strange election as just over half of the 3,045 members were present; the others either did not make it to Taiwan after the KMT retreat or were absent for other reasons. The votes were cast — but because less than half the members validated the result, the assembly had to vote a second time. Chiang obliterated Hsu, 1,507 to 48.

‘EXAMPLE FOR DEMOCRACY’

Photo: Hung Mei-hsiu, Taipei Times

This wasn’t the first time Hsu ran against the KMT. Six years prior, at the former KMT headquarters of Nanjing, Hsu finished dead last in the election for vice president.

While the KMT banned the formation of new political parties during the Martial Law era from 1949 to 1987, there were two legal parties who retreated from China to Taiwan alongside the KMT — in addition to Hsu’s party, there was also the Young China Party (中國青年黨). Both were allowed to participate in the first National Assembly elections in 1947.

Power was heavily skewed in favor of the KMT from the very beginning. During the first National Assembly elections in 1947, the KMT nominated more than 2,000 candidates while the Young China party and Democratic Socialist Party both fielded fewer than 400 each.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The KMT dominated the polls, with the other two parties winning less than 80 seats each. Both parties threatened to leave the government in protest, and the KMT ended up forcing some of its members to concede their seats in a controversial move that led to much internal discontent. But the assembly was still heavily dominated by KMT members, rendering the “opposition” as not much of an opposition.

“The KMT altered the election structure in 1954 and also strengthened its under-the-table negotiations so it could further control the elections,” historian Wang Yu-feng (王御風) writes in the book, History of Elections in Taiwan (台灣選舉史).

In fact, a short biography published to commemorate Hsu’s death in 1958 acknowledges the futility of challenging the KMT, stating, “When he ran for vice president and president, he knew that it was an impossible feat but he still pushed through, just to set an example for the nation’s democracy.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

TOTALITARIAN RULE

Chiang was not supposed to run again for president in 1960 due to constitutional term limits. Chiang claimed that he was against amending the constitution to keep him in power, and instead the National Assembly amended the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist Rebellion (動員戡亂時期臨時條款), which allowed him to run for infinite terms as long as the Temporary Provisions were still in place.

With nobody opposing Chiang and the threshold of National Assembly members required to validate the vote lowered, this move solidified the party’s iron grip over Taiwan.

“Our compatriots across the world have requested in unison that President Chiang run for another term,” announced election chairman Chia Ching-teh (賈景德) to about 50,000 people gathered in front of Zhongshan Hall. “To respect popular opinion, the National Assembly has amended the [Temporary Provisions] so he can continue to serve as president. Judging from how jubilant you all are today, I believe that our compatriots overseas will feel the same. Especially our compatriots on the mainland who are suffering, they must be even more overjoyed to hear this news.”

“Now, chant loudly with me: Long live the Republic of China! Long live the Three Principles of the People! Long live President Chiang!”

Of course this did not sit well with many non-KMT politicians, including Lei Chen (雷震), a former KMT official who was expelled in 1954 for criticizing the party in his publication, Free China (自由中國).

A few months after Chiang was re-elected, Lei and leaders from both the China Democratic Socialist Party and the China Youth Party as well as a number of independent politicians of both Chinese and Taiwanese origin gathered at the Democratic Socialist Party headquarters to discuss how to counterbalance the KMT’s increasingly authoritarian rule.

They decided to form the a new party called the China Democracy Party (中國民主黨), and immediately began preparations.

The KMT watched carefully, but it seems that an Free China article comparing the formation of opposition parties to the Yangtze River flowing east — something that cannot be stopped — was the last straw. Three days after the article ran, Lei and three others were arrested for spreading communist propaganda and harboring communists — standard excuses for political arrests during the Martial Law era.

Chiang personally made sure that Lei would spend at least 10 years in jail with no possiblity of appeal. When a KMT politician spoke out against the verdict, his party membership was suspended for one year.

“Naturally, after the Lei Chen incident, nobody would dare to oppose Chiang when he announced that he would run for yet another term, and he easily won again in 1966,” Wang writes.

All hopes were dashed for the KMT to propagate real democracy after that. The party would reluctantly do so several decades later under the pressure of Taiwan’s democracy movement, but that’s a story for another time.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them