Taiwan’s transition to democracy from 1979 through 1992 is something the people of Taiwan can be truly proud of. It changed the equation of the country’s identity and laid the foundation for a brighter future.

The major events that bookended and shaped the transition process are well-known: the Kaohsiung Incident of 1979, the formation of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in 1986, the end of martial law in 1987 and the passage of legislation and constitutional reforms from 1991 to 1992, establishing a fully elected legislature and enabling direct presidential elections in 1996.

However, much less is known about one of the most important drivers in support of this transition to democracy: dangwai (黨外, “outside the party”) movement magazines published between the 1970s and 1980s. What follows is an overview of these publications, the people behind them and the various phases they went through.

Photo: Yang Ming-yi, Taipei times

Before 1979, there were a few initiatives to get opposition publications off the ground, including the Taiwan Political Review in 1975, but generally these efforts were relatively small-scale and short lived, as they were quickly shut down by the still repressive ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT).

ANXIOUS ERA

However, in 1979, the situation changed: after US de-recognition of the KMT as the government of China in December 1978, there was a period of anxiety and tension, when the authorities postponed the Legislative Yuan and National Assembly elections for which the dangwai had formed a loose coalition.

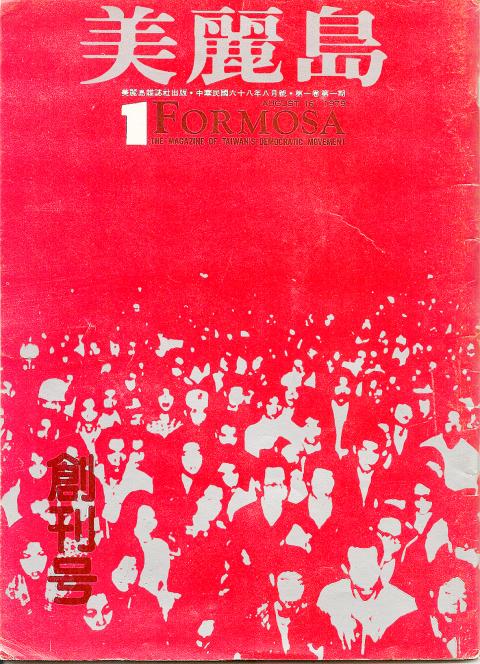

Photo courtesy of Gerrit van de Wees

In the summer of 1979, two dangwai groups started a magazine: 1980s (8十年代), led by Kang Ning-hsiang (康寧祥) and edited by Antonio Chiang (江春男), and Formosa Magazine (美麗島), led by veteran activist Huang Hsin-chieh (黃信介).

During the Fall of 1979, both quickly gained popularity, but also were the subject of increasing restrictions by the (often secret) police and subject to virulent attacks by pro-unification gangsters, the “anti-communist-heroes.”

FORMOSA INCIDENT

Photo courtesy of Gerrit van de Wees

This all culminated in the now well-known Formosa Incident: the Human Rights Day celebration on Dec. 10, 1979 in Kaohsiung that turned ugly when police surrounded a peaceful crowd of some 10,000 and started to use teargas. Chaos ensued, and three days later the KMT government arrested virtually all dangwai leaders and accused them of “sedition” and “trying to overthrow the government.”

Three trials took place from March through May 1980. To the outside world, it laid bare a very repressive political system and a highly biased judicial system. The Chicago Tribune headlined its commentary “Comic Opera Trial.”

During this period, no dangwai magazines were allowed, but by the end of 1980, the KMT went ahead with the delayed elections for the legislature and National Assembly. Relatives of the imprisoned opposition leaders ran as dangwai candidates and scored major victories: Yao Chia-wen’s (姚嘉文) wife Chou Ching-yu (周清玉) in the National Assembly, and Chang Chun-hung’s (張俊宏) wife Hsu Jung-hsu (許榮淑) and Huang Hsin-chieh’s younger brother Huang Tien-fu (黃天福) in the Legislative Yuan.

These election wins empowered them to look for ways to spread the message about the goals and objectives of the democratic opposition, the continuing lack of human rights and democracy and the plight of those imprisoned.

In the spring of 1981, several magazines saw the light of day: 1980s (8十年代) resumed publication, while Hsu Jung-hsu started Cultivate (深耕) and Chou Ching-yu CARE Magazine (關懷). By the Summer of 1982 the number of dangwai magazines had grown to about a dozen.

Between the Summer of 1982 and the following year, these magazines were joined by a second generation of magazines, such as Taiwan Panorama (博觀), published by Kaohsiung Incident lawyer You Ching (尤清), Vertical-Horizontal (縱橫) and Bell Drum Tower (鐘鼓樓), published by Huang Tien-fu, and was later succeeded by Neo Formosa Weekly (蓬萊島).

CENSORSHIP

The increase in the number of publications led to a crack down by KMT authorities. There were four levels of censorship: removing or blacking out a particular offending article; banning the publication (though many remained available under the counter); confiscation; and suspending the publication’s license (often circumvented by registering several similar-sounding titles).

The reasons for censorship included revealing the harsh prison conditions under which the Kaohsiung Incident prisoners were held; discussing Taiwan’s isolated international status; establishing an opposition party; and writing unflattering profiles on the KMT and the family of the nation’s authoritarian ruler, Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石).

The magazines also examined several political murders that took place during the early 1980s: the murder of the mother and twin daughters of human rights lawyer Lin I-hsiung (林義雄) on Feb. 28 1980, the murder of Taiwanese-American scholar Chen Wen-chen (陳文成) of Carnegie Mellon University in July 1981 and the murder — on American soil — of China-born US writer Henry Liu (劉宜良), who was writing an unflattering biography of then-President Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國).

DANGWAI MAGAZINES — 3G

By the beginning of 1984, a third generation of dangwai magazines appeared: Lin Cheng-chieh (林正杰) started Progress (前進), while Deng Nan-jung (鄭南榕) started Freedom Era Weekly (自由時代 ). These magazines were different from previous generations in that they were started by people who had no direct connection to the Kaohsiung Incident.

This new generation of publications and those who ran them also initiated street protests to put more pressure on the authorities.

The widespread pressure for liberalization and democratization from activists prompted an increase in censorship from the KMT authorities: in October 1984 there was an infamous “Thought Police” meeting attended by the Garrison Command, the head of the Government Information Office, Chang Ching-yu, and James Soong (宋楚瑜) of the KMT. The minutes of the meeting, which read like something out of Nineteen Eighty-Four, were leaked.

From early 1985, there was an intensified confiscation campaign with more than 1,000 police dedicated to confiscating publications. The authorities also started “legal” proceedings against several magazines, such as Neo Formosa Weekly, which led to the imprisonment of future president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁). By September 1985 some 95 percent of all publications had been confiscated.

However, the pressure to end martial law and move towards a representative democracy intensified through street protests: the dangwai movement — as it came to be called — was able to field increasingly large numbers of people in street protests. The most well-known was the “Green Ribbon Campaign” started by Deng on May 19, 1986.

This pressure at home was accompanied by pressure from abroad: in Washington a small group of key senators and congressmen held frequent hearings on the lack of democracy and human rights in Taiwan, urging the KMT authorities to end martial law and move towards a democratic political system.

THE END OF MARTIAL LAW

In the second half of 1986 Taiwan’s political scene witnessed rapid change: leading dangwai members established the DPP, then-president Chiang Ching-kuo announced in October to the Washington Post that he would end martial law, and in the December Legislative Yuan and National Assembly elections, the democratic opposition made major gains.

In 1987, Chiang Ching-kuo made good on his promise, and on July 14 of that year lifted martial law. However, it was replaced by a National Security Law, with a particularly onerous Article 100, which continued to inhibit freedom of speech. Chiang Ching-kuo passed away on Jan. 13 1988, and was succeeded by then-vice-president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝), but much of the undemocratic political system remained.

One of those who continued to fight for “100 percent freedom of speech” was Deng. In December 1988 he published a draft constitution for a free and democratic “Republic of Taiwan” in his magazine. To the authorities this was “against the law.” He was charged with “sedition,” and police surrounded his office.

On April 7 1989, after a three-month siege, police stormed the office. But rather than surrender and be subjected to questioning and imprisonment, Deng set his office on fire, perishing in the flames in an ultimate expression of freedom of speech.

Pressure from home and abroad, and Lee’s guiding hand, eventually resulted in the momentous events in May 1992, when the National Security Law and Article 100 were abolished, the “Period of Communist Rebellion” was ended and Lee passed legislation and constitutional amendments providing for the election of all seats in the legislature and National Assembly by the people of Taiwan, and for direct presidential elections in 1996.

Taiwan had made its transition to democracy, and was ready for a new chapter in its future as a free and democratic nation, in large part thanks to the courageous men and women of the dangwai magazines.

— Gerrit van der Wees is a former Dutch diplomat, who served as editor of Taiwan Communique from 1980 through 2016.

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South