Nov. 06 to Nov. 12

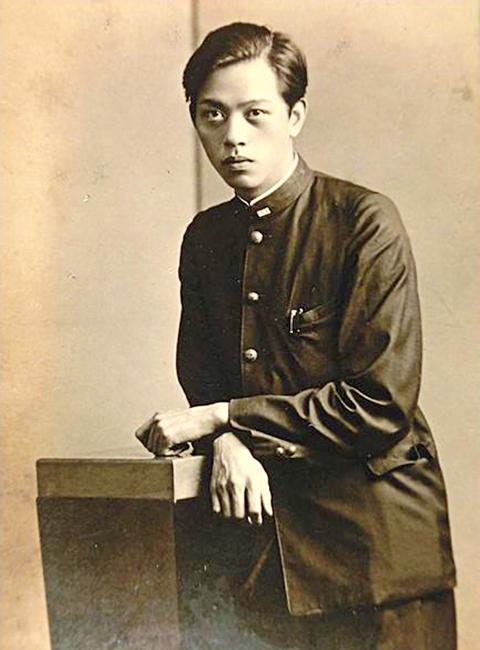

Su Beng (史明) snuck into Taiwan from Japan in October 1993, the last leg via fishing boat from Yonaguni island. He climbed ashore to a familiar sight in the dead of night — 44 years previously, he had landed not too far from this the exact same spot after his flight from China, also during the wee hours.

Su was soon picked up by the police and taken to Taipei to stand trial for illegal entry among other charges. Defiant as ever, he proclaimed, “I did not come back to visit my relatives. I came back to overthrow the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) colonial rule and to fight for Taiwan’s independence.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It might have been an audacious thing to say in his day, but this was no longer the Martial Law era, and the long-time blacklisted activist managed to avoid jail time. After having spent only three years of his adult life in Taiwan, Su was home for good.

PREPARING THE COMEBACK

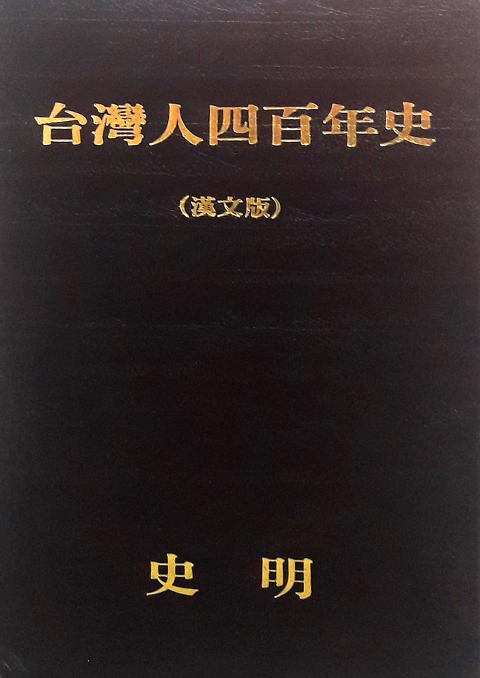

Su had been living in Japan since 1952, when he fled Taiwan after his plan to assassinate former KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) was leaked. He remained active in independence activities, and is best known for publishing the book Taiwan’s 400-Year History (台灣人四百年史) in 1962. Written in Japanese, it was translated in to Chinese in 1980 and English in 1986.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

As Taiwan showed signs of democratization in the 1980s, Su contemplated returning home to continue his fight on the frontlines.

“All signs pointed to the weakening of the KMT’s grip over Taiwanese society,” he writes in his autobiography. “The people have also started developing a Taiwanese consciousness. Thus, I was very optimistic about the political future of Taiwan.”

Su had set aside a substantial amount of money earned through his restaurant in Tokyo, and also began training future activists. These ordinary citizens would travel to Japan on the pretext of tourism but would actually spend seven to 10 days with Su, learning about activism and Taiwanese history. Su writes that he hosted groups as large as 30 people.

Photo: Liu Hsin-te, Taipei Times

His plans were put on hold when five of these trainees were arrested in May 1991 and charged with sedition in what would be known as the Taiwan Independent Association incident (獨台會案). However, public outcry led to the repealing of the Punishment of Rebellion Act (懲治叛亂條例) and the amending of the Criminal Code to only punish those who used or planned to use violent and forceful means to commit sedition. Since the defendants only published and disseminated material about Taiwanese independence, they were acquitted.

When another group of his trainees founded a pro-independence association in Kaohsiung’s Fengshan District (鳳山), Su could not wait any longer. Once home, however, he realized that times had changed and the armed resistance that he had formerly engaged in would not work in a gradually liberalizing Taiwan.

“I knew that Taiwan did not have room for armed resistance,” he writes. “After all, most people are afraid of such activities due to the false ‘democracy’ provided by the enemy. So I turned my focus to mentoring and organizing.”

On a side note, one of the things that surprised Su after his return was the proliferation of beef noodle shops.

“Taiwanese did not eat beef during the Japanese era,” he writes.

WORKING FOR THE COMMUNISTS

In 1942, Su was unhappy with his task as a secret agent for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Japanese-occupied Shanghai and Suzhou.

“I came to China to join the resistance. Why am I still interacting and dealing with the Japanese? Perhaps it’s because I looked Japanese, I could enter Japanese military institutions with ease. My job was not even dangerous.”

Born on Nov. 9, 1918, Su first left Taiwan in 1937 to study political economics in Tokyo. During this time, he voraciously read books on anarchism and socialism, and was especially drawn to Marxism, which was his main inspiration for heading to China to fight the Japanese.

“First of all, through Marxism I took notice of the CCP and started learning about China. I felt that China was a place where socialism could prevail,” he writes. “Secondly, China had became the main battlefield for resisting the Japanese Empire. I believed that in order to rid Taiwan of Japanese imperialism, the best way was to start from China.”

Su remained in the Japanese-held areas until the end of the war. He says that he initially had a good impression of Communist leader Mao Zedong (毛澤東).

“But that all changed when I entered the Communist-ruled areas,” he writes, as he moved to Zhangjiakou in Hebei Province in 1946. Over the year, he became disillusioned with the CCP, noting that they had no intent of liberating the oppressed and were instead creating a system of fear and terror. Later he completely gave up on them after seeing the brutality of the class struggle.

Su finally saw combat, engaging in guerilla warfare with the KMT. He also oversaw a division of Taiwanese troops who were initially sent to China during the Chinese Civil War by the KMT but captured by the CCP. The poor treatment of these soldiers made Su realize that “the Communists never saw Taiwanese as one of their own,” which only strengthened his identity and desire to leave China.

As China fell to the CCP in 1949, Su fled back home only to find that the KMT’s behavior was no better than that of the CCP.

“Turns out, both Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong believe in authoritarianism,” he writes.

For Su, there was only one final path to take.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name