July 31 to Aug. 6

To the Qing Empire, they were fan (番), or barbarians. The Japanese called them the Takasago, or high mountain people. And the Chinese Nationalist Party referred to them as shanbao (山胞), or mountain compatriots.

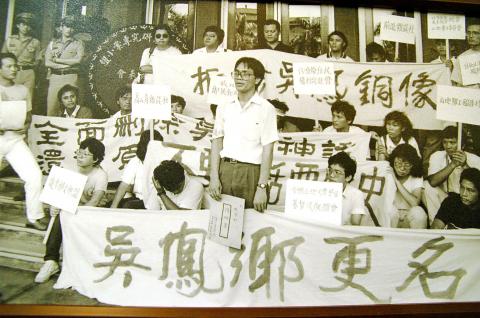

In late 1984, the Aborigines of Taiwan decided that they would no longer bear the designation handed to them by the colonizers. On Dec. 29, a group of 23 Aboriginal and Han Chinese intellectuals got together and formed the Taiwan Aboriginal Rights Association (台灣原住民權利促進會), with one of their demands being that the government officially call them yuanzhumin (原住民, or original inhabitants), which is the term used today.

Photo courtesy of Hsieh San-tai

“The organization was the first one that included the term ‘Aborigine’ in its name,” writes Icyang Parod in the book, Compilation of Historical Material on Taiwan’s Aboriginal Movement (臺灣原住民族運動史料彙編). Now minister of the Council of Indigenous Peoples, Icyang was a key figure in various early Aboriginal movements.

It seemed like a simple and harmless request, but the process took almost 10 years. On Aug. 1, 1994, National Assembly finally granted the request along with an article in the constitution to protect indigenous rights. Aboriginal activists continue to fight for various issues today, but the rectification of their designation was seen was seen as a major victory to a long-mistreated people. Since 2005, Aug. 1 has been observed in Taiwan as Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

A PURE NAME

Photo: Hsieh Wen-hua, Taipei Times

In 1983, along with two other Aboriginal National Taiwan University students, Icyang launched the publication High Green Mountain (高山青), which highlighted the danger of Aboriginal cultural extinction and called for Aborigines to start a self-help movement.

“Through looking at their own situation, they hoped to awaken an Aboriginal consciousness,” Iwan Nawi writes in the book, Taiwan’s Aboriginal Movement at the Legislative Yuan (原住民運動與國會路線). “Although this consciousness originated on campus, it quickly spread through the urban Aboriginal population as well as urban mainstream society.”

Icyang writes that the Aboriginal Rights Association was originally to be named “High Mountain Tribe Rights Association” (高山族權利促進會), but a month before the organization launched, current Kaohsiung Bureau of Education Director Fan Sun-lu (范巽綠) proposed that they use the term Aboriginal instead. The term was formally adopted after an intense debate during the organization’s first meeting.

Photo: Lu Chun-wei, Taipei Times

“It was a pure term because it had never been officially used before,” Icyang writes. “The use of the term symbolizes the fact that our organization not only sought to resolve tangible Aboriginal social issues, it also fought for our status as well.

“We not only want to have our people identify with being Aborigines, through the term we also want to let the Han Chinese know that this land originally belonged to us. We will not dwell on the methods through which they obtained this land, but they should at least respect our rights and status.”

The newly-formed Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) supported the movement, using the designation in its party constitution written in 1986. The same year, the Presbyterian Church also officially adopted the designation, and usage spread among the church’s roughly 80,000 Aboriginal members.

Photo: Taipei Times

CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

But the push for the government to formally eliminate “mountain compatriots” in favor of “Aborigines” did not take shape until 1991.

That year, the National Assembly convened to amend the constitution. One of the agenda items concerned guaranteed seats in the Legislature for “mountain compatriots.” If passed, this would be the first time the hated designation appeared in the constitution.

Icyang and other protestors marched to the National Assembly meeting grounds at Yangmingshan’s Zhongshan Hall, and after being blocked by security several times, managed to deliver their petition. They made several requests, but Icyang says that the designation change was the only one reported by the media. To his dismay, no action was taken.

The National Assembly convened again to amend the constitution a year later, and this time more than 1,000 protestors marched to Zhongshan Hall. Icyang writes that the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was hesitant to designate the Aborigines as the original owners of the land, because that would imply that the Han Chinese were a foreign people and the KMT a foreign regime, leading to further problems. The National Assembly then suggested zaozhumin (早住民, or earlier inhabitants) or xianzhumin (先住民, or first inhabitants), which the activists deemed unacceptable.

By the end of the session, Icyang and his people remained “mountain compatriots.”

The DPP backed the Aborigines during the constitution amendment session of 1994. In April, then-president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝), who had opposed the designation change in 1992, publicly addressed the “mountain compatriots” as Aborigines in a speech. This likely prompted the reticent KMT to add the designation change to their agenda as well.

In June, 3,000 people marched for Aboriginal rights. A month later Lee promised Aboriginal activists that they would get their wish. The assembly voted 196-63 in favor.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall