July 3 to July 9

Japan had just celebrated the 20th anniversary of its rule over Taiwan when Yu Ching-fang (余清芳), self-appointed Grand Marshal of the Benevolent Nation of the Great Ming (大明慈悲國), declared war against the colonial government.

On July 6, 1915, Yu announced that he had been “appointed by heaven to rally the righteous and drive out the bandits.” He lamented that Japan, which was once tributary to imperial China, had “betrayed its master” and invaded its territory.

Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“I have gathered the heroes of the four seas to attack and annihilate the ‘dwarf bandits.’ Providing peace to the good while rooting out the violent, I shall ease the people’s suffering and save the lives of all living beings,” Yu said.

Thus began the Tapani Incident (?吧哖事件), the largest and last armed anti-Japanese revolt by Han Chinese. The toll on the Taiwanese side is still disputed, with some sources claiming up to 30,000 deaths. The latest numbers released by the Tainan City Cultural Affairs Bureau in 2015 indicate 1,412 dead and 1,421 sentenced, which excludes two districts in Kaohsiung where the records have been lost.

VARYING MOTIVES

Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Academia Sinica researcher Paul Katz writes in When the Valleys Turn Blood Red that not all participants shared Yu’s nationalist and patriotic sentiments toward China, which had transitioned from the Qing Empire to the Republic of China. Some wanted to establish an imperial state in Taiwan with Yu or another rebel leader as emperor, and others spoke of an independent Taiwan.

Katz adds that many did not share Yu’s distaste of being ruled by foreigners, but were more unhappy about the way they were ruled. The Japanese reviewed the causes of the rebellion in a newspaper article, citing excessive taxes, Japanese arrogance and police brutality, among other factors. During interrogation sessions, many rebels cited these factors, but Katz argues that “the ethnicity of their overlords did not appear to have been a decisive factor.”

He gives the example of a laborer, who stated during his interrogation that “all I wanted was to farm in peace, not have to pay taxes and open up new forest lands at will.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“We now have to pay huge amount of taxes, and all profitable enterprises have been monopolized by the Japanese … I couldn’t take it anymore. If we could become part of China again, we would no longer have to suffer like this,” complained another rebel.

Some also say they joined because Yu had promised them prominent positions, land and tax breaks if the uprising succeeded.

“We should at least consider the possibility that many participants … chose to act as the result of more mundane sentiments such as a desire for material gain or simply to be left alone,” Katz writes.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The most interesting cause, however, was Yu’s use of folk religion and messianic rhetoric that included an impending apocalypse and salvation. This was nothing new, as Katz writes that these beliefs had been circulating around southern Taiwan for some time.

“Some recruits may have joined Yu’s cause … merely as a means of protecting themselves and their families from an impending apocalypse,” Katz writes.

RELIGIOUS PERSUASION

The first indication of Yu’s anti-Japanese tendencies surfaced in 1909, when the 30-year-old former patrolman was sent to a vagrant camp for joining a secret society that aspired to overthrow the colonial government. Katz writes that Yu’s uprising shared several similarities to this group, including the “belief in an imminent apocalypse, the promised arrival of a rescue force of soldiers from China and the advent of a savior who lived in the mountains and possessed a magic sword and imperial seal.”

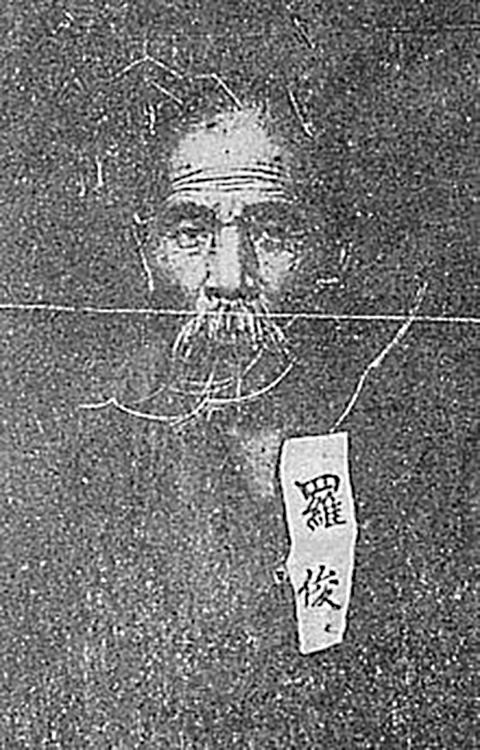

Upon his release, Yu became associated with the Hsilai Temple (西來庵) and started recruiting followers across Taiwan in 1914, also raising money for the uprising under the guise of temple repairs. He met and joined forces with co-conspirators Lo Chun (羅俊) and Chiang Ting (江定) during this time.

Yu proclaimed that the temple’s deity told him that Japanese rule would only last 20 years, and the end was near. The three leaders propagated the idea of a savior born near Tainan who could heal sicknesses and was destined to become Taiwan’s emperor, with some followers even believing that person was Yu, according to Chiu Cheng-lue’s (邱政略) book, Looking Back 100 Years After the Tapani Incident (百年回首?吧哖事件).

“Regardless of gender and age, all followers had to kneel down before Yu,” Chiu adds.

The leaders also had their followers purchase amulets that, combined with following a vegetarian diet for 49 days and reciting prayers, would make them impregnable to swords and bullets, adding that they could disable the Japanese soldiers through magic and annihilate them within three days.

The leaders claimed that the time would be ready to strike when the sky turned dark for seven days and the reinforcements from China arrived.

Unfortunately, the Japanese caught wind of the plan and started arresting the rebels, including Lo. Yu briefly went into hiding before making his edict and started attacking various police stations in the area. The Japanese retaliated, culminating in the major clash in Tapani, located in today’s Yujing District (玉井) in Tainan.

Yu’s forces didn’t stand a chance despite his magical claims. He was betrayed by locals during a feast and arrested just a month after the rebellion. He was executed in September. Chiang held out until the next spring, but was also caught and hung, effectively ending the resistance.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)