March 13 to March 19

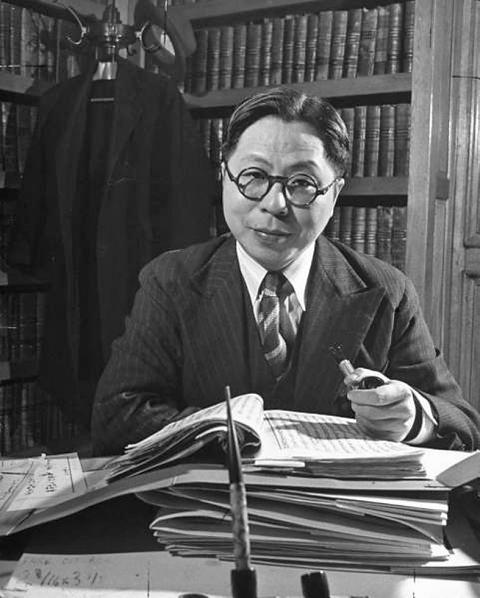

On March 17, 1954, K.C. Wu (吳國楨) was stripped of his Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) membership and relieved of all his duties. Not that he was performing any of them — by then, he had resigned his post as governor of Taiwan and fled with his family to the US after a prolonged conflict with other party members, including Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), son of then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石).

The move came after Wu noticed on a road trip in March 1953 that the front wheels of his car had been tampered with, which he saw as an assassination attempt. Two months later, he successfully left the country under the pretense of nursing a sickness and accepting an honorary doctorate from his alma mater, Princeton University.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“I’m not coming back,” he reportedly told Judicial Yuan president Wang Chung-hui (王寵惠), who came to see him off at the airport.

GOING PUBLIC

Wu kept quiet at first — he was invited to speak at a Double Ten National Day gala in New York City, but only talked about supporting the Nationalists’ fight against Communism. But in November, reports surfaced accusing him of using government money to live a luxurious life in the US. He spent the next three months trying to clear his name, which garnered him more media attention.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

He started to reveal more — when asked by Chicago’s WGN-TV why he came to the US, he replied that it was for both health and political reasons. Before that, however, he had maintained that it was entirely due to his sickness.

“In the political climate of those times, this was essentially a public challenge to Taiwan’s government,” his biography published by the Liberty Times states. CBS sent a reporter to his house the next day, and “there was no going back.”

On Feb. 16, 1954, he completely opened up about his conflict with the government, one of the points being that they did not care to win the support of the Taiwanese as well as overseas Chinese.

Liberty Times file photo

“We also need to win the support of free countries, especially the US. But if we don’t practice true democracy in our territories, this will not happen,” he said.

According to his biography, he then repeatedly told reporters in English, “The present government is too authoritarian.” These words made the major US newspapers.

This started a war of words between Wu and the KMT across the Pacific Ocean, leading up to his expulsion from the party.

SIMMERING FEUD

Wu had worked for the KMT since 1926 and was once a close associate of the Chiang family. He retreated to Taiwan with the KMT in 1949, and in 1950 he became governor after Chen Cheng’s (陳誠) resignation.

During this time, he clashed with other major KMT members over many issues, including greater self-governance for Taiwanese and increased democracy. The book Who’s Afraid of Wu Kuo-chen? (誰怕吳國楨?) by Yin Hui-min (殷惠敏) states that he even directly brought up the idea to Chiang Kai-shek of allowing multiple political parties.

“We have the best people on our side, where would we find able people to form an opposition party?” Chiang reportedly replied.

Wu had clashed with Chiang Ching-kuo while still in China, and this feud continued in Taiwan when he intervened in a mass arrest by Chiang’s special agents. Several more incidents took place over political arrests, and Wu further incurred Chiang’s wrath by refusing to provide funds to the anti-communist youth organization China Youth Corps (救國團), which he compared to communist and Nazi youth leagues in his biography.

Unable to carry out his political ideals and unhappy with the direction the Chiangs were going toward, Wu tried to resign several times, but to no avail. Chiang Kai-shek was intent on passing on power to his son, and was hoping that Wu would support him. Wu refused, and finally Chiang Kai-shek had no choice but to accept his resignation.

After his expulsion from the party, Wu only amped up his rhetoric, writing several letters to Chiang criticizing the government’s one-party rule, political intimidation through special agents and lack of press freedom among other issues.

He also accused Chiang of nepotism, saying that he “loves power more than his country, and loves his son more than his people.”

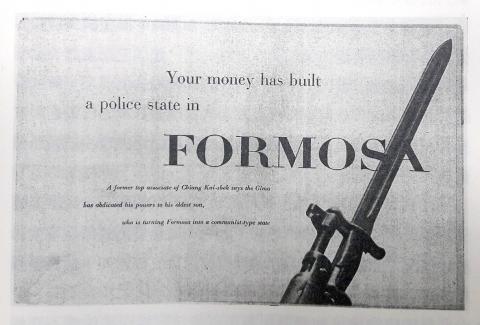

Probably most notable is the article he penned for Look magazine, titled Your Money has Built a Police State in Formosa, stating that Taiwan has turned into a “communist-type state.”

However, Wu’s efforts did not deter the US from continuing to support and provide funds to the KMT regime. As George H. Kerr writes in Formosa Betrayed, it was the height of the McCarthy Era and the US was more concerned about fighting communism, and “Wu’s voice was drowned in the clamor of more aid for Chiang.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall