March 6 to March 12

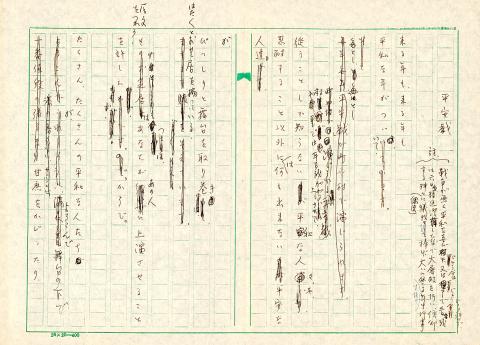

Last month, the family of the late poet Tu Pan Fang-ko (杜潘芳格) donated 340 manuscripts to the National Central Library. The three languages these documents were written in — Japanese, Mandarin and Hakka — represent Tu Pan’s literary journey through Taiwan’s turbulent history.

Living through the Japanese and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regimes, the political climate dictated what language Tu Pan wrote in for most of her life. It wasn’t until she was in her 60s that she began to use her native Hakka.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Writers like Tu Pan are often included in the “translingual generation” (跨語言的一代), a term coined in 1967 by poet Lin Heng-tai (林亨泰) to describe those who were educated in Japanese but were forced to pick up Mandarin under KMT rule. He specifically referred to those who came of age under the colonial government’s Japanifcation policy, which officially began in 1936.

“When Japanese rule ended, we were in our 20s. Unlike the older generation who may have had some exposure to an education in Chinese, we were strictly educated in Japanese since childhood. While we were no longer forced to speak Japanese, it was the language we were most comfortable writing in. We had to be determined enough to make another shift, which was to learn Chinese,” he wrote.

A National Museum of Taiwan Literature publication states, “This was especially problematic for writers, as they lost their rich vocabulary, grammar and ability to express complex thoughts. Many stopped writing, and others had to study for years before they could write in Chinese.”

Photo: Chen Yi-min, Taipei Times

But like other members of this generation, being forced to use a new language did not dampen Tu Pan’s literary passion.

“If you ask me why I write, you might as well ask me why I live,” she said in a 2004 interview with Ink Literary Monthly (印刻文學生活誌). “My words have a life of their own … they simply appear, and I’m compelled to write them down.”

Born on March 9, 1927 to wealthy and educated parents, Tu Pan’s family moved to Japan when she was an infant. They returned when she was about six years old, and enrolled in Japanese schools up to the college level. Her work is shaped by many conflicts in her life — being bullied by Japanese schoolmates, questioning the role of women in society, defying her parents’ wishes by choosing her own husband and losing several family members in the 228 Incident.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The KMT banned writing in Japanese in 1946, and Tu Pan did not publish anything for more than a decade. She was also busy helping her husband and raising seven children during this time. In 1966, she published her first Mandarin poem, written in Japanese and translated by fellow writer Wu Cho-liu (吳濁流).

Most of her early works in Mandarin were translations of Japanese originals. Lee Yuan-chen (李元貞), a professor of Chinese literature, writes that they often suffered at the hands of various translators, who were often male and did not grasp the nuances of the female perspective.

“This is one of the reasons she wasn’t as influential as she could have been,” Lee writes. “Such is the fate of many members of the translingual generation.”

NATIVE TONGUE

After the lifting of martial law in 1987, Hakka intellectuals founded Hakka Affair Monthly magazine (客家風雲) and held a “Return My Native Language” (還我母語) march on Dec. 28, 1988.

Tu Pan was never fully comfortable writing in Mandarin, and Japanese remained the main language she used during the creative process. One day, however, she noticed that “some verses started to naturally form in my native Hakka.”

“I picked the words up and wove them into Hakka poems,” she continues. “But it was difficult, as I had a limited literary vocabulary.” Figuring out how to write down Hakka sayings that did not have Mandarin counterparts was also a challenge.

She published her first Hakka poem in 1989, and soon it became a mission to help keep the language alive.

“It is time for some soul-searching as we Hakka people are being assimilated by other groups,” she wrote in a 1994 column for The Commons Daily (民眾日報). “We should love our native language and find ways to improve it and turn it into an elegant and beautiful language … I hope that Hakka writing can develop and become a trend.”

She says she wanted to follow the example of Dante, who wrote The Divine Comedy in Italian instead of the prevalent Latin, adding that if the work becomes popular enough, the language it uses will increase in prestige.

In addition to new pieces, she also reworked some of her old poems in Hakka, which were often not straight translations. The original 1977 Mandarin version of Peace Play (平安戲), for example, doesn’t include a Hakka-specific euphemism that the 1995 Hakka version does.

Tu Pan then penned several poems stressing the importance of speaking one’s mother tongue. After it became acceptable to speak in languages besides Mandarin, she also became worried that Hakka was losing ground to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese).

“Recently, everybody is speaking Taiwanese … But there are many types of Taiwanese. Aboriginal languages and Hakka are also Taiwanese,” she wrote in a 1993 piece.

And after writing for her entire life in Japanese and Mandarin, she denounced the two languages:

“[They] are two languages that we were forced to learn by authorities, and represent our enslavement. Mandarin and Japanese are merely a common means for us to communicate — it is not our native language. We Taiwanese have been culturally assaulted for 100 years; our language taken away by outsiders.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an