Robert Storey, author of the first four editions of the Lonely Planet Taiwan guide and more than a dozen other guide books, died on Dec. 26 at his home on Taiwan’s southeast coast. He was 63 years old.

Though Storey lived a private life in the foothills outside of Taitung City, his guides were familiar to a huge number of English-speaking travelers who came through Taiwan from the late 1980s to the early 2000s, and thousands more who traveled through East Asia.

In fourteen years with Lonely Planet, Storey authored or co-authored a dozen different guides, including those for South Korea, China, Vietnam and the first ever English guide to Mongolia.

Photo: David Frazier

MAN OF MANY TALENTS

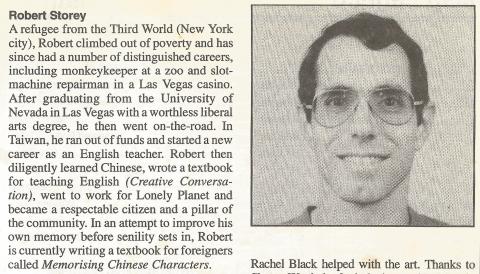

Authors of those books were allowed to pen their own biographical blurbs, and in his 1994 Lonely Planet Taiwan guide (3rd edition), Storey described his early life (see picture above).

Storey came to Taiwan in 1986 almost by accident, stuck here on a two-day layover. He quickly returned, and stayed for the next three decades until his death.

In his early years in Taiwan, he published his own guide, Taiwan On Your Own. The DIY effort caught the attention of Lonely Planet, who commissioned him to write their inaugural Taiwan guide, Taiwan — a travel survival kit, published in 1987.

At that time, Lonely Planet was fast becoming one of the world’s most popular travel guides by offering the kind of unvarnished advice you might get from a fellow budget traveler, uninvited opinions and all. Storey joined the guide’s legendary early generation of writers, and Lonely Planet founder Tony Wheeler once referred to him as “our straight-arrow writer” for his chaste habits and scrupulous attention to detail. This status only fell into question once, when, while working on a Vietnam guide, Storey’s driver was secretly soliciting bribes from hotels.

In the Taiwan guide, Storey took advantage of a Lonely Planet writer’s freedom to be sarcastic, off-the-cuff and tactlessly direct. He wrote of the Nantou County’s Aowanda Forest, “So many tour buses come up here on weekends that it’s a wonder the mountain doesn’t collapse.”

Of road rules, he scoffed, “Basically, there aren’t any. When the Taiwanese get behind the wheel of a car or on the seat of a motorcycle, they smell blood.”

To blend into local society, he advised, “The Chinese love name cards. Get some printed before or immediately after you arrive in Taiwan. Throw them around like confetti.”

Storey also cautioned visitors to beware of Taiwan’s flowery rhetoric. “One examination given to prospective employees involves taking a single meaningful sentence and rewriting it into a two-page essay with no increase in content. Many people also talk this way.”

The publication of Storey’s first Taiwan edition came the same year as the end of martial law in Taiwan and during the nation’s electronics boom. Not only did a combination of social liberalization and easy pay for English teaching jobs draw in a new, budget-conscious expatriate community, it also marked an era when Westerners began to settle down and stay. Many were drawn from Southeast Asia’s hippy trail or lured to teach in cram schools, and a huge number landed with Storey’s Lonely Planet guide in hand.

1994 EDITION — TIME CAPSULE

The 1994 edition now reads like a time capsule for that era. In the book, the acronym he used to describe Taiwan was NIE, “newly industrialized economy.” He prefaced a passage on e-mail services, saying it was intended only for “the real computer freaks,” as there were only two service providers and Internet connection time cost NT$14 per minute. The population was 21 million, per capita income around US$10,000 and there was one motorcycle for every two people. Of Taipei, he wrote, “Unless the wind is blowing, the air is toxic.” And in that pre-MRT era, it was.

When I first arrived in Taipei in 1995, I was reading Storey’s 1994 Taiwan guide on the plane. But it was only 15 years later that I realized that the geeky face in the front of my guidebook was actually attached to a real person. I bumped into Storey by total happenstance in Kasa, a sleepy Taitung cafe. Though his name was known to most Taiwan expats, only a couple of my Taitung-based friends had ever met him. I mainly remember Robert for his dry, intelligent sense of humor. We met again over the years and traded e-mails and books.

Of all of the guidebooks Storey worked on, he held on to his authorship of the Taiwan guide tenaciously. Early generation Lonely Planet authors owned their guides’ copyrights, and Storey refused to relinquish his Taiwan guide copyright. Lonely Planet could only proceed by rewriting the guide from start to finish, which they did with the help of three writers for the fifth edition in 2001.

Storey spent nearly all of his 30 years in Taiwan in Taitung, and the descriptions in his 1994 guide hint at his reasons. “Taitung is likely to remain a quiet backwater for a long time” and is “blissfully free of the traffic jams, noise and pollution which characterize Taiwan’s big cities.”

“On the east coast it’s easy to forget where you are. The sparsely inhabited rugged landscape could pass for the coast of New Zealand.”

His Taitung chapter in that book was just six and a half pages, and many of his friends believed this brevity was a smokescreen, a way of keeping Taitung a secret.

Storey suffered for years from Crohn’s disease, an often debilitating and painful ailment of the intestinal tract. The disease kept him from drinking alcohol, but otherwise he did not reveal his suffering publicly.

After Storey stopped writing for the Lonely Planet in 2001, he devoted himself to a new passion, the open-source Linux operating system, which he wrote about on a site called Distrowatch. He also consulted for Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture and three years ago opened a guest house in Taitung city.

Storey relinquished his US citizenship late last year to become a citizen of Taiwan, an event which his friend say gave him much satisfaction.

Friends knew him as humorous, knowledgeable and a person to go to for advice on difficult questions. He is survived by his wife and remembered fondly by the small group of friends who knew him.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) announced last week a city policy to get businesses to reduce working hours to seven hours per day for employees with children 12 and under at home. The city promised to subsidize 80 percent of the employees’ wage loss. Taipei can do this, since the Celestial Dragon Kingdom (天龍國), as it is sardonically known to the denizens of Taiwan’s less fortunate regions, has an outsize grip on the government budget. Like most subsidies, this will likely have little effect on Taiwan’s catastrophic birth rates, though it may be a relief to the shrinking number of

Since its formation almost 15 years ago, Kaohsiung rock band Elephant Gym (大象體操) has shattered every assumption about contemporary popular music, and their story is now on screen in a documentary titled More Real Than Dreams. It’s an unlikely success story that says a lot about young people in Taiwan — and beyond. For a start, their sound is analog. In the film, guitarist Tell Chang (張凱翔) proudly says: “There is no AI in our sound.” His sister, bass player KT Chang (張凱婷) is the true frontwoman — less for her singing abilities than for her thunderous sound on the instrument. Fast like