Audiences have come to expect interesting, challenging and even quirky works from the choreographers chosen for the annual Meimage Dance Company’s New Choreographer Project, and this year’s crop did not disappoint.

However, one piece blew me away: The Man, choreographed by Tien Tsai-wei (田采薇), a Taiwanese dancer with Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, and Wuppertal-born Jan Mollmer, whom Tien met while studying dance in Essen, Germany, at the same school that produced Bausch.

That is not to say that the solos by Japan-based Chien Lin-yi (簡麟懿), a dancer with Noism, and New York City-based Hung Tsai-hsi (洪綵希) were not engaging, for they were, but they paled somewhat in bookending The Man.

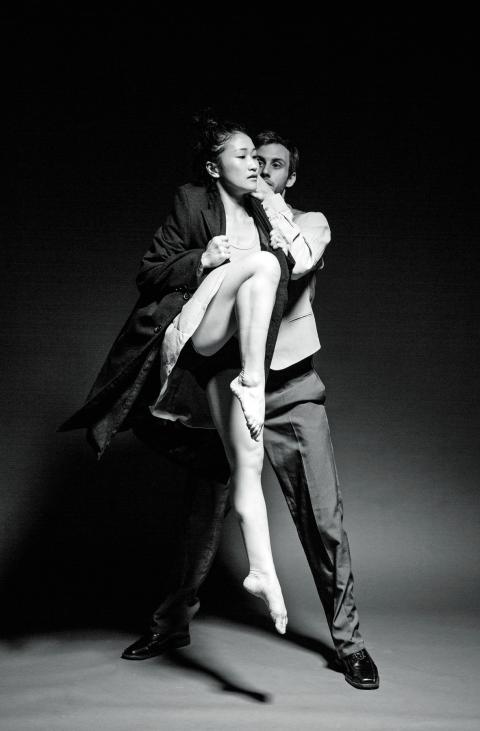

Photo courtesy of Terry Lin

Control was the thread connecting the three works at the Eslite Bookstore’s Xinyi branch Performance Hall over the weekend and dancers certainly are all about control. They train day after day, year after year, to control their muscles and limbs by repeating exercises, stretches and movements until the moves become muscle memory.

Tien and Mollmer’s The Man had, for a time, what appeared to be a domineering male figure, who controlled and manipulated his partner by means of a man’s black overcoat she was wearing — until he did not and she began to control him with his coat.

However, that was just one part of a multi-level story of a relationship, one that twisted and turned as deftly as the dancers themselves. It was impossible to predict where the 30-minute piece was going as the mood shifted from romance and humor to darkly fraught tension, the menace of a ringing black rotary telephone, to death, humor and back again.

The only elements on the stage were two dancers of widely disparate heights, a pair of men’s black overcoats, an old-fashioned phone on a side table and an iron, yet the result was magic.

There were so many memorable parts: Tien following Mollmer — and vice versa — around with one hand flipping the back of their coats from underneath so that they looked like puppies wagging their tails, wanting to play; Mollmer, arms and hands hidden within his coat, bending close to Tien, her arms hidden under her coat, to pick her up; Mollmer’s robotic, muscle-isolating movements as he pretended to light a cigarette at the beginning of the piece, contrasted with his tippy-toed disjointed stumbling in the second half. Tien’s comedic bit, which involved the use of the phone’s receiver and the iron as electric shock paddles to “revive” Mollmer, brought much needed relief.

In the end, Mollmer buttons Tien up inside his coat, her arms with his in the sleeves, her head poking out just above the buttons. When they pull their hands out of the pockets to replicate the cigarette lighting that opened the duet, you cannot tell if his hands are controlling hers or hers controlling his.

The duet made me think of another Taiwanese who studied in Essen and was heavily influenced by the dance theater style of Pina Bausch — Lin Mei-hong (林美虹), who was the director of the Tanztheater des Staatstheaters Darmstadt for many years before moving to the Landestheater Linz in Austria.

I had almost the same feeling after watching The Man as I had after seeing Lin’s Darmstadt dancers perform Schwanengesang at the National Theater in March 2010 — Lin and Tien/Mollmer give dance theater a good name and I would love to see more of their works.

Talking with Tien afterwards, it turns out that what she and Mollmer had performed was an excerpt of a 50-minute duet. I hope they have a chance to perform the full work in Taiwan sometime.

Chien's solo, Chiu (囚), was a martial arts-influenced piece set to samisen music by the Yosida Brothers. It fully lived up to the pictograph that is the character chiu, a person confined within a square.

Chiu was a fine demonstration of body and muscle control, largely confined to a square of white light on the floor. The one segment where Chien stepped out of that block of light for more than a moment, he was replaced by a cartoon shadow projection of himself, replicating his previous movements.

Hung’s solo, Lan huzi (藍鬍子), which translates as “blue beard,” turned out to be inspired by the French folk tale of the murderous, controlling Bluebeard and the wife that outwits him, with a voiceover in English reading the part of the story where the wife enters the forbidden room where the bodies of her predecessors are kept.

I would have liked the solo more if Hung had not kept her hair hanging down in front of her face (a la the Japanese horror flick The Ring) for a large portion of the dance, though I understood the effect she was striving for.

The show closed with an improvisational piece by Tien, Hung and Chien that wasn’t listed on the program, which saw them use their smartphones and social media to make connections with each other — Chien finding Tien’s street address in Germany on Google Maps and projecting it onto one of three screens on the back while she looked up his address in Japan and projected it onto another of the screens — and connections with the audience as well, and then as using the phones’ cameras to project their performance onto the screens.

It was a clever way to bring home the New Choreographer Project goal of bringing expatriates back to Taiwan and forging connections.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)