They say you save the best for last, but when writing a book, perhaps that is not always the case.

Granted, Bruce Jacob’s latest effort, The Kaohsiung Incident in Taiwan and Memoirs of a Foreign Big Beard, is geared toward academics or people with a specific interest in Taiwanese history and politics who would probably find the entire book interesting or at least valuable. But the second half of the book, which contains Jacobs’ memoir, is so much more engaging, unique and personal that it could make a fun read for anybody. It is almost a shame to put it last.

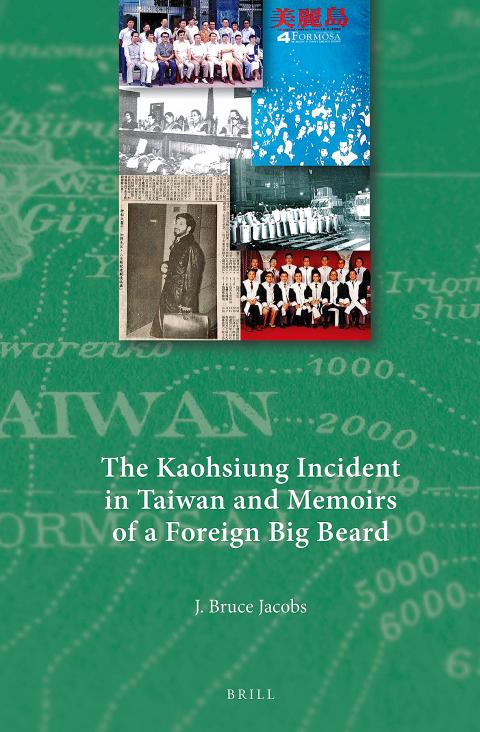

Most of it has to do with the organization of the book, which contains two distinct parts. The first half details the events, aftermath and implications of the 1979 Kaohsiung Incident, where a pro-democracy rally organized by Formosa Magazine (美麗島雜誌) turned violent and was used as an excuse for the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) to arrest most of the political opposition leaders. To Jacobs, this event laid the foundation for Taiwan’s democracy.

Jacobs, a professor of Asian Languages and Studies at Monash University in Australia, also details the murders of the mother and twin daughters of Lin I-hsiung (林義雄), who was one of the key figures arrested due to the incident. Jacobs was personally acquainted with the family, and in the second part of the book, we follow him as he goes from a college student interested in Asia to the “bearded foreigner” who was officially accused of being involved in the murder case and placed under police protection in Taiwan.

Jacobs does begin by providing political context during those times — from the loosening of absolute KMT control through late president Chiang Ching-kuo’s (蔣經國) reforms to the rise of the dangwai (黨外, “outside the party”) movement.

However, even in this section there are so many specific facts and names that it would be hard to become engrossed in the book without much previous knowledge of Taiwanese political history. Because of the sheer amount of details thrown out, the writing at times becomes choppy and a bit difficult to follow. And as the story moves on, I found myself wondering why Jacobs was using a literal translation of terms such as “Black Hand Gang (黑手黨),” instead of “organized crime,” which would have been far clearer for readers unfamiliar with Taiwan. Longer introductions to some people, such as Chang Fu-hsiung (張富雄) — who is only mentioned once without any explanation — would have helped as well.

About 60 pages — a little more than one-third of the book — detail the military trials of the eight key defendants as well as the civil trials of 33 involved persons. For the average reader, it would seem a bit dry, but for research purposes it is valuable information since the original text was published in Chinese-language newspapers. Sleep deprivation, torture and forced or false confessions are frequently mentioned — and it is surprising that newspapers printed transcripts of the entire trials during that time. The fact that these people were still convicted also speaks to the condition of Taiwanese justice under martial law.

Much of this latter information, including the fate of those involved, is told in an ordered, list-like format that is easy to cross reference, and Jacobs does provide analysis on how this event has contributed to Taiwanese democracy.

JARRING HALVES

The tone changes significantly in the second part, as the writing becomes more lively and personal, and this is where the book really shines. You don’t have to be an academic to enjoy this part, as it is a fascinating tale of a foreigner entangled in local politics who must defend himself against a powerful authoritarian state.

Breaking from the previous academic style, Jacobs writes about his emotional reactions to the events, including a scene where he curses out a policeman in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), and another one where he ends up in tears.

Much is mentioned about how Jacobs’ ordeal was framed differently in the local press, thereby providing a look into the media environment of those days. What happened to Jacobs is rather bizarre and almost comical since he was eventually able to get away without much harm, but it is chilling when thinking of local political prisoners who did not have such protection as a foreigner during the Martial Law era. It also reflects the absurdness of the security and justice system under the days of one-party rule.

The memoir continues as Jacobs returns to Taiwan throughout the 1990s (still being watched even with the lifting of martial law) and stays well-paced and vivid with many compelling scenes that further add to the absurdity of his situation. The Lin family murders remain unsolved.

Obviously, the second half of the book would make no sense without the context provided in the first part. However, Jacobs inserts himself into the first half on several occasions and also references the first half in his memoir, and this makes one wonder if there could have been any way to take it further and combine the two halves into a part-scholarly work, part-memoir that would be one comprehensive piece without two jarring halves.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was out in force in the Taiwan Strait this week, threatening Taiwan with live-fire exercises, aircraft incursions and tedious claims to ownership. The reaction to the PRC’s blockade and decapitation strike exercises offer numerous lessons, if only we are willing to be taught. Reading the commentary on PRC behavior is like reading Bible interpretation across a range of Christian denominations: the text is recast to mean what the interpreter wants it to mean. Many PRC believers contended that the drills, obviously scheduled in advance, were aimed at the recent arms offer to Taiwan by the